15 November 2022: Ukraine | Twitter part 2

Culture as decolonisation from the Russian Empire // Twitter, the ‘Trust Thermocline’, and how to break complex systems.

Welcome to Just Two Things, which I try to publish three days a week. Some links may also appear on my blog from time to time. Links to the main articles are in cross-heads as well as the story. A reminder that if you don’t see Just Two Things in your inbox, it might have been routed to your spam filter. Comments are open.

1: Culture as de-colonisation from the Russian Empire

Most of the coverage of the Ukraine-Russia war is about the military campaign or the geopolitics of it. So I was struck to read something by the Guardian’s Chief Culture Writer, Charlotte Higgins, about cultural aspects of the conflict. She had visited Kyiv recently and taken in a performance at the Opera House, still staging a wide-ranging repertoire despite the war:

Operas by Verdi, Puccini and Mozart, and ballets such as Giselle and La Sylphide, are on the playbill, despite the almost daily air raid sirens. But there is no Eugene Onegin in sight, nor a Queen of Spades, and not a whisper of those Tchaikovsky staples of ballet, Sleeping Beauty or Swan Lake. Russian literature and music, Russian culture of all kinds, is off the menu in wartime Ukraine. It is almost a shock to return to the UK and hear Russian music blithely played on Radio 3.

In general, across Europe, Russian music and plays continue to be performed. Books by Russian authors are still on sale. Although Putin speaks of Russian performers being “cancelled” because of the war, this is exception rather than the rule.

Yes, Cardiff Philharmonic Orchestra removed the ‘1812 Overture’ from a concert in March, figuring that Tchaikovsky’s celebration of Russian military success might cause offence when actual Russian cannon were firing at the Ukraine. (The decision was ridiculed at the time, but perhaps seems less strange with hindsight). And yes, the regime apologist—or advocate—Valery Gergiev isn’t being asked to conduct in the West right now. But mostly Russian performers are still welcome,

assuming they have offered a minimum of public deprecation of the killing and destruction being visited on Ukraine.

This is not the case in Ukraine, and Higgins argues in her piece that this is because, for Ukrainians, the war has become “a war for decolonisation”, in the words of the Ukrainian poet Lyuba Yakimchuk:

This decolonisation involves a “total rejection of Russian content and Russian culture”, as the writer Oleksandr Mykhed told the Lviv BookForum recently. These are not words that are comfortable to hear – not if, like me, you spent your late teens immersed in Tolstoy’s Anna Karenina and Chekhov stories;... not if you adore Stravinsky and would certainly be taking a disc of The Rite of Spring to your desert island.

But obviously you have a different perspective on this if you are Ukrainian. Its shared his with Russia, and with the Soviet Union, has involved the suppression of Ukrainian art and artists, their murder or their appropriation:

It has included the absorption of numerous Ukrainian artists and writers into the Russian centre (such as Nikolai Gogol, or Mykola Hohol in Ukrainian), and the misclassifying of hundreds of artists as Russian when they could arguably be better described as Ukrainian (such as the painter Kazimir Malevich, who was Kyiv-born but Russian, according to the Tate).1 It has meant that writing in Ukrainian has at times been proscribed – Ukraine’s national poet, Taras Shevchenko, was banned from writing at all for a decade by Tsar Nicholas I. This silencing has encompassed the extermination of Ukrainian artists, like the killing, under Stalin, of hundreds of writers in 1937, known as “the executed renaissance”.

(Malevich, ‘Landscape (Winter), after 1927. Public domain).

Of course, there’s also a brutal Soviet history here that goes well beyond culture.

So this history places the Ukraine is a different position to Russian culture than, say, Britain had to German culture during the Second World War, when German composers were often on the repertoire of the lunchtime concerts at the National Gallery:

“We have had cultural occupation, language occupation, art occupation and occupation with weapons. There’s not much difference between them,” the composer Igor Zavgorodniy tells me. In the Soviet period, Ukrainian culture was allowed to be harmlessly folksy... But Ukraine was not expected or allowed to carry a high culture of its own. At the same time, Russian artistic achievement was lauded as the very apex of human greatness.

Putin’s repeated insistence that Ukraine has no history and no identity separate from that of Russia makes this cultural conflict sharper. And it is sharpened again by the way in which the Russian regime uses the country’s cultural history—“the myth of the ‘Russian soul’, and so on—as a form of soft power.

Of course, there may be a time beyond the war when Ukrainians can again enjoy Russian music and books. But that time is not now:

Some Ukrainians I speak to hope that one day, beyond the end of the war, there will be a way of consuming Russian literature and music – but first the work of decolonisation must be done, including the rereading and rethinking of classic authors, unravelling how they reflected and, at times, projected the values of the Russian empire. In the meantime, “My child will be perfectly all right growing up without Pushkin or Dostoevsky,” says (playwright Natalya) Vorozhbit. “I don’t feel sorry.”

2: Twitter and the ‘Trust Thermocline’

Yesterday, in part one of this post, I wrote about Musk’s mismanagement of Twitter, and the possible explanations for it. Today, I’m going to explore the ways in this might make Twitter collapse—apart from just running out of money, which also seems like a distinct possibility.

One of Musk’s problems is that he has given his users enough reason to look for alternatives, and put up with the pain of the learning curve. Gareth Edwards (aka ‘John Bull’) had a memorable thread on the social media site—pretty much the last thing he posted before he left it—on the idea of the Trust Thermocline.

The idea of the Thermocline is having a bit of a moment. On his Roblog Rob Miller used the same idea recently to discuss the relationship that organisations have with the truth. (Meaning something like ‘ground truth’).

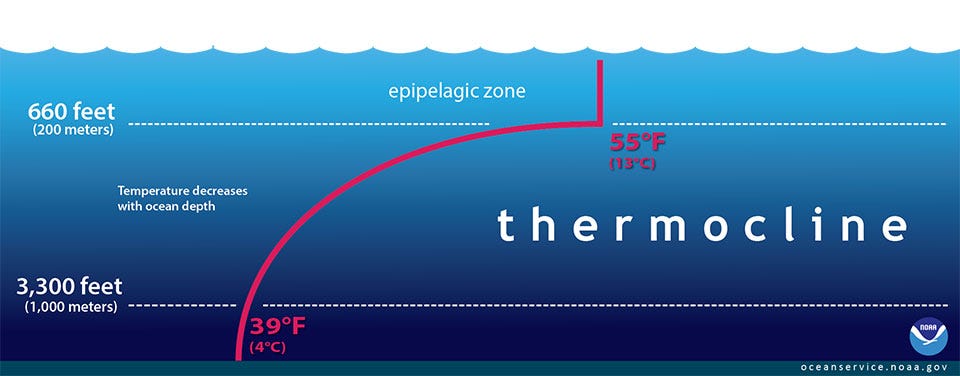

I should probably back up a bit at this point. An actual thermocline is a feature of deep sea temperature. As you go down, the temperature drops steadily, until you hit the thermocline, then suddenly. Here’s Rob’s explanation of it:

In the ocean, temperature decreases with depth: the deeper you go, the colder it gets. But sometimes, what’s called a thermocline forms: a temperature barrier, a point at which the temperature changes rapidly. Go above the thermocline and the water is warm; pass beneath it, and it’s suddenly cold. This can have huge ramifications for life in the ocean, preventing the passage of oxygen and nutrients past the barrier.

(More about the actual thermocline than you probably want to know can be found at https://oceanservice.noaa.gov/facts/thermocline.html. Image: National Ocean Service).

In his Twitter thread, Gareth Edwards uses this as a metaphor for trust:

The Trust Thermocline is something that, over (many) years of digital, I have seen both digital and regular content publishers hit time and time again. Despite warnings (at least when I've worked there). And it has a similar effect. You have lots of users then suddenly... nope... So why does this happen? As I explain to these people and places, it's because they breached the Trust Thermocline.

The way this works is because users have some sunk costs (time, habit, emotional commitment, familiarity) with the media they use. They don’t just suddenly up sticks and leave when the product gets worse or the cost keeps nudging up. But there comes a point where their irritation exceeds the value of the service:

(T)hey'll only move when they hit the Trust Thermocline. The point where their lack of trust in the product to meet their needs, and the emotional investment they'd made in it, have finally been outweighed by the physical and emotional effort required to abandon it.

But once they go, they don’t come back again.

In some ways this is a product of a complex system. And it is one of the reasons why people try not to perturb complex systems too much—because you can’t know the point at which complex systems start to behave differently.

Adam Roach noted that various Twitter systems had already started to behave differently:

One of the fascinating things is watching Twitter’s behavior change, hour after hour, as various microservices go offline... It’s like the end of 2001 when Dave is destroying HAL and HAL keeps on going, just gradually degrading, but continuing to work as far as his remaining capacities allow him to... But it's only a matter of time before a core function is gone, and no one on staff knows how to get it back up.

(Any excuse to use an image of HAL. Image by Cryteria, via Wikipedia, CC BY 3.0)

The system, in other words, is for the moment degrading gracefully, at least until it simply topples over. Joe Bak-Coleman had a thread on the issues in managing complex systems, and what to look out for:

If I wanted to keep an eye peeled for failure I'd look for a phenomenon known as "critical slowing down". Systems about to transition will take longer and longer to get back to normal. Ad sales, latency, etc.. Will it? This happened to Digg after a large shift. Digg went from influencing the flow of internet traffic (the "digg effect") to a ghost town after a big redesign caused cascading failures across its code, then userbase and ultimately advertisers.

Bak-Coleman is clear that he doesn’t know if Twitter’s systems are going to fail, but if you set out to put complex systems at risk one way to do it is to make big changes to their infrastructure, technical systems and people, all at the same time:

I can't tell you if Twitter will fail, but I can say (Musk)’s doing everything I could think of break it or any complex system.

There are many differences between SpaceX and Tesla, on the one hand, and Twitter on the other. But one of the biggest ones is that both SpaceX and Tesla involve complicated systems. Twitter is a complex system.

j2t#393

If you are enjoying Just Two Things, please do send it on to a friend or colleague.

All of these histories are complex, of course. Wikipedia says: Malevich was born to a Polish family who settled near Kiev in Kiev Governorate of the Russian Empire during the partitions of Poland. His parents had fled from the former eastern territories of the Commonwealth (present-day Kopyl Region of Belarus) to Kiev after the failed Polish January Uprising of 1863. Malevich spoke Polish, Russian and Ukrainian.