15 November 2021. COP26 | Transport

Living in Glasgow during the COP26 clampdown; living in a low-car world

Welcome to Just Two Things, which I try to publish daily, five days a week. Some links may also appear on my blog from time to time. Links to the main articles are in cross-heads as well as the story.

#1: Living in Glasgow during the COP26 clampdown

Now that the tents have been folded and the circus has left town, it’s worth mentioning what the experience of living and working in Glasgow felt like during the event.

Pat Kane touched on this in the piece I shared here last week. Specifically, he mentioned that Glasgow had managed to issue integrated transport tickets to delegates, despite having failed to do this for its actual citizens over an extended period of time.

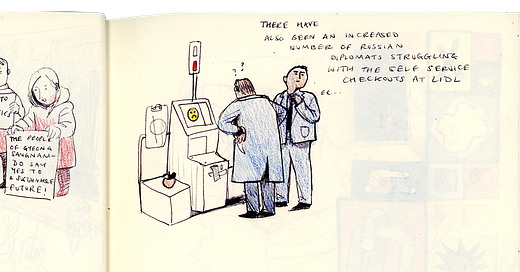

Another perspective comes from Rebecca Guthrie’s idiosyncratic newsletter, Scrap Papers. Rebecca is doing an illustration Masters at Glasgow, and her newsletter has a sharp eye for quotidian details, and usually comes with illustrations. Here are some extracts.

The COP26 conference rolled into town without much fanfare, but still managed to spread a feeling of tension across the city. During a run around the park, I see that my usual route is blocked off by metal mesh fencing at the Kelvingrove Museum, and cops stand at all possible entrances. Diplomats, identified by their conference lanyards, suits, and general air of studied officiousness, are admitted through gates. Occasionally they escape their conference centres in Finnieston and the West End and traverse other parts of the city.

(Copyright Rebecca Guthrie)

Of course, politicians can’t go anywhere without a cavalcade these days, and COP26 is no different. I’ve got a personal theory that our experience of being yelled at by the police outriders while the motorcade goes by is one of the things that alienates people from politicians:

On the first Monday night of the conference, I am waiting to cross the road near the motorway when a police officer on a motorcycle draws up and barks an order at me to not move. Presently, a full security detail of vehicles speeds past, followed by “The Beast” - the unique black Cadillac that transports the US President around on state visits.

(Copyright Rebecca Guthrie)

And then there are the demonstrations, of course:

I go to the biggest march, on Saturday the 6th of November. The feeling that something could go terribly wrong hangs in the air, a condition for all events attended by masses of people at the moment. As I walk in the drizzling rain and wind with thousands of others, a party atmosphere develops, aided by the constant sound of rhythmic percussion. Extinction Rebellion can be criticised for their reckless gluing of people to commuter trains, but they have rehearsed enough that their drum section is now pretty tight.

I haven’t written here about transport for a while, and Jeremy Williams has an interesting review of Melissa and Chris Bruntlett’s book Curbing Traffic, about the experience of living in the Netherlands’ (relatively) car-free culture.

The Bruntletts are Canadians who moved their family from Vancouver to Delft after visiting the Netherlands to study its transport culture.

The difference between the Netherlands and north America is stark, when it comes to travel choices:

(T)o provide a national comparison, in the Netherlands a third of trips are by car, a third by public transport and a third by active transport. In the United States, 90% of journeys are by private car, with 5% each for public and active transport.

There are some interesting points here, one being that although it’s assumed that somehow the Netherlands (and the Dutch) are somehow different when it comes to active travel, that difference has been constructed through political and social decisions:

(As the book explains, Dutch transport culture was created. It wasn’t there already. From the 1970s on, car culture was incrementally and deliberately restrained. Streets were redesigned. Planning codes were adapted. Urban space was reclaimed from cars. People defend the status quo with “the familiar refrain of ‘we’re not the Netherlands'” the authors observe, “but as Delft proves, neither was the Netherlands.”

Each chapter of the book looks at a different aspect of the human experiences of low car living, and unravels its consequences. It turns out that these are usually benign:

There’s a chapter on the ‘child-friendly city’, and how Dutch children enjoy far greater freedom than in other places, because the streets are so much safer and they can transport themselves. Closely connected to that, low car environments allow people to mix and meet outside more often, which builds trust. People don’t experience the space outside their homes as a hostile and noisy place, so they spend more time there and it’s easier to build community.

It also turns out that active transport infrastructure can reduce inequality and support employment, and that car-free public spaces can encourage local spending and boost the economy.

Every so often often I see a consumer research survey that says that people won’t “give up” anything to achieve climate change—and obviously, the phrasing of the questions already frames the answer. More considered research—where people can evaluate options—tells a different story.

The car is an epitome of the kind of financialised world we have been living in for the past forty years, or more. There’s an argument, but for another time, that the car created the forms of consumer capitalism that emerged a century ago (with GM’s invention of segmented markets and designed obsolescence in the the mid 1920s).

There are lots of trends that suggest that people are fumbling towards a world in which wellbeing is more important to them than consumption (‘the great resignation’ is one example, which I have written about here). Unlike the car, though, we don’t yet have a straightforward symbol of what that looks like. Financialised capitalism is so pervasive, so everyday, that it crowds other possibilities out of our imaginations.

j2t#207

If you are enjoying Just Two Things, please do send it on to a friend or colleague.