17th May 2021. Imagination | Rivers

A revolution of the imagination; Recovering the Los Angeles River

Welcome to Just Two Things, which I try to publish daily, five days a week. Some links may also appear on my blog from time to time. Links to the main articles are in cross-heads as well as the story.

#1: A revolution of the imagination

I spent some of last week at a (virtual) conference organised by Hawkwood Centre for Future Thinking, and among several outstanding talks I’m going to mention the one given by Transition Towns founder Rob Hopkins. The images in this piece all come from screenshots of his talk: I hope he forgives their use here.

It was based on his 2020 book, From What Is to What If and was a call for “a revolution of the imagination”. As someone who believe in the value and social power of visioning and preferred futures, this obviously struck a chord.

Hopkins started by defining imagination as “the ability to see things as if they were otherwise.” But, in the words of the American abolitionist Mariame Kaba, “We live in a system that has been locked into a false sense of inevitability.” My imperfect notes suggest that Kaba may also have talked about “the decline of imagination since the 1990s.”

The function of imagination is to bring “longing into the world”—I’d say that what this does is to create a narrative gap that we are then moved to fill. (In the Seeds of Good Anthropocenes approach, this is what the “mature seeds” are designed to do.

For example, although as a species we only landed on the Moon in 1969, we had been there many times before in our culture, whether with Tintin as our guide, or Frank Sinatra.

(Image: Rob Hopkins)

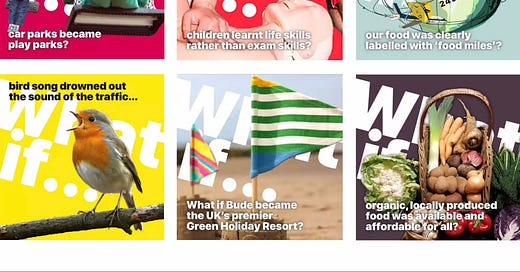

He noted several examples of creating such imagination—the work of James McKay in Leeds, visualising different versions of a future Leeds. Or Transition Bude, which ran an extended “What If?” campaign to change future perceptions. Or the Swedish Green party, which used images of a desirable current life as a way to disrupt the present.

Hopkins shared the “imagination sundial”—a wheel based on four elements, of space, place, practices, and pacts.

(Image: Rob Shorter, CC BY-SA 4.0)

Space is about creating what I’d call “looseness”—a bit more time, a bit more slack in the system, whether it’s a four day week or a form of Universal Basic Income. (And it’s possible to believe that Kaba’s “decline of the imagination” has something to do with the way that work regimes and technology have combined to squeeze our loose time, even our opportunities for boredom.

Place is about disrupting the way we see the world around us—whether that is Extinction Rebellion foresting Waterloo Bridge, or “parking days”, where artists buy parking spaces for the day but don’t park cars in them.

Practices is about creating mental space for imagination—quite literally. Both memory and imagination are developed in the hippocampus, and the hippocampus shrinks in response to stress (specifically in response to cortisol).

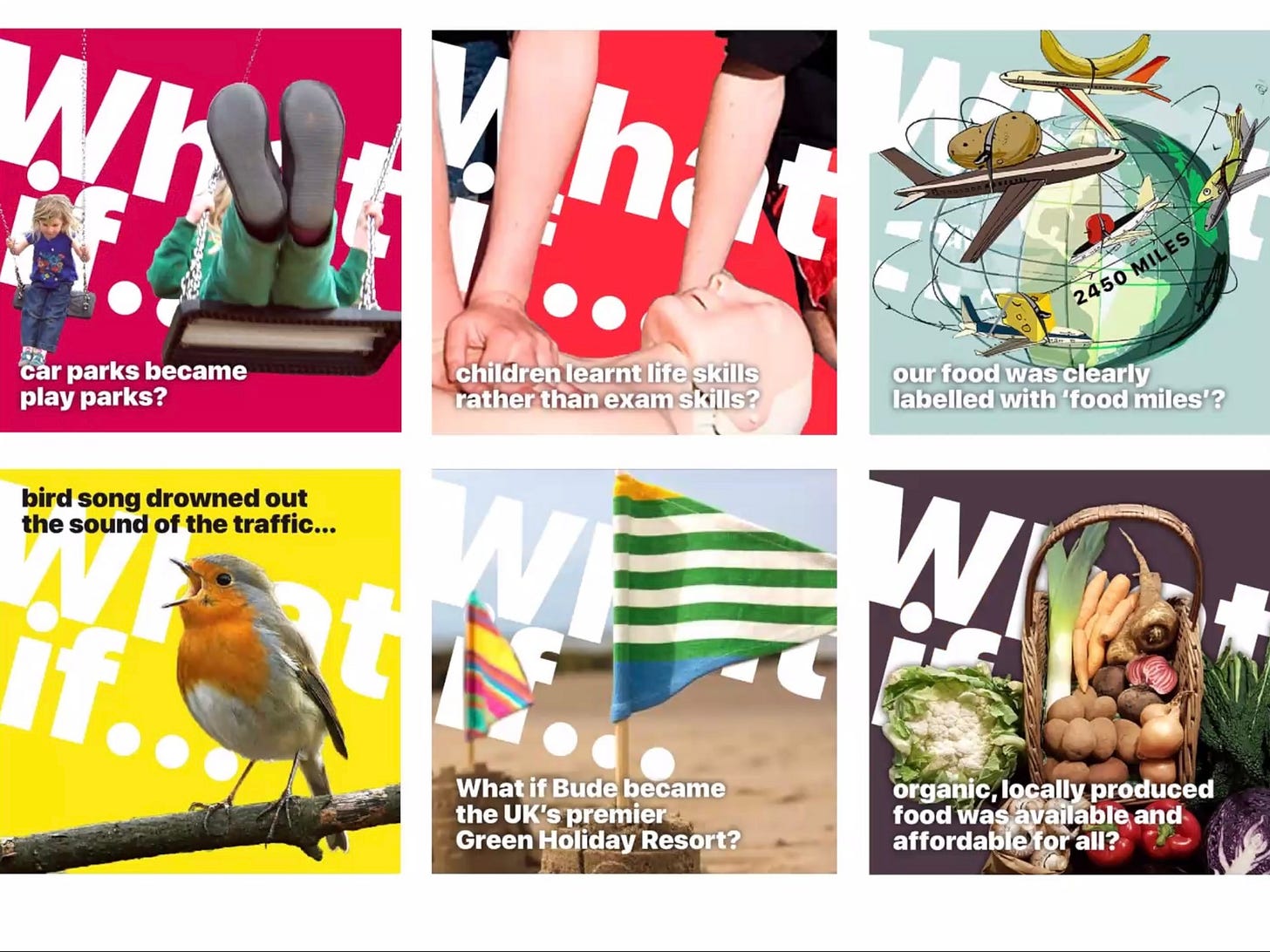

One example of Practices is the Transition Town Anywhere workshop. Another is the Dundee Art Angel project which treats all its participants as artists, rather than clients or service users, even though its working with mental health issues. One of the requirements of participants is that they illustrate how they felt when they joined and how they feel now.

(Image: Art Angel, via Rob Hopkins)

What if? questions also work as a practice. What if Tooting’s bus turning circle was a local green? What if the majority of food eaten in Liege was grown in the fields around the city?

Pacts are about making agreements to get things done. Bologna’s Civic Imagination Office, for example, enables new spaces and places to come into being by agreeing the commitments that the city will make—in exchange for the resources that other parties agree to bring in to make change happen.

I’d noticed Rob’s book when it came out last summer, although I hadn’t bought it. The model sounds interesting so I’ve ordered the book to understand it better.

#2: Recovering the Los Angeles River

The idea of bringing rivers back to life within cities has become more mainstream as the research that shows that it both improves environmental outcomes and improves our wellbeing.

The most famous example is in South Korea, where a multilane highway was demolished to open up the river to citizens again, even if the actual story is a bit more complex.

Los Angeles’ river recovery plan is now finally coming to fruition. Metropolis talked to Mia Lehrer, the master planner behind the initial scheme to revitalise the Los Angeles River.

The current scheme involves renovating an 11-mile stretch of the river, improving habitat, restoring wetlands, and adding bikeways. It’s been approved, but there are some financial details to be sorted out. Lehrer describes the project—now being developed by Gehry—as a life’s work:

I started by becoming active with Friends of the Los Angeles River, cofounded by poet Lewis MacAdams. At the same time, there were a series of professional charrettes ... where people were really starting to look at the river and asking questions like, “What does this really mean to recapture this river?” It seemed like a pipe dream... We (also) began working on getting to know the river and understanding its issues by helping in cleanups. The cleanups were, believe it or not, these really wonderful experiences, like learning to harness a beast. The river channel collected garbage of such incredible proportions.... There was an understanding (on the part of the city engineers) about managing floodwater, but that was it. They were mowing down all the vegetation that was slowly coming back.

The Los Angeles River as it is now. Image: City of Los Angeles.

The current scheme involves renovating an 11-mile stretch of the river, improving habitat, restoring wetlands, and adding bikeways. It’s been approved, but there are some financial details to be sorted out. Lehrer describes the project—now being developed by Gehry—as a life’s work:

I started by becoming active with Friends of the Los Angeles River, cofounded by poet Lewis MacAdams. At the same time, there were a series of professional charrettes ... where people were really starting to look at the river and asking questions like, “What does this really mean to recapture this river?” It seemed like a pipe dream... We (also) began working on getting to know the river and understanding its issues by helping in cleanups. The cleanups were, believe it or not, these really wonderful experiences, like learning to harness a beast. The river channel collected garbage of such incredible proportions.... There was an understanding (on the part of the city engineers) about managing floodwater, but that was it. They were mowing down all the vegetation that was slowly coming back.

But as with the South Korean scheme, there are also likely to be losers: the city needs to manage the regeneration issues that follow this kind of development, as Planetizen has noted in its response to the development plan.

Los Angeles River as it could be. Image: Mia Lehrer and Associates

The interview with Lehrer also touches on LA’s longer water problems. She thinks they can manage this, with some smart ecological thinking:

Our Mediterranean-style climate means almost anything can grow here if you add water. Yet because of the drought and our fragile water infrastructure, we have to become more water independent. It’s a great opportunity and an important challenge. For us, it means looking to the plants native to our own communities and Mediterranean regions for inspiration—those that have adapted to long, dry summers and do best with very little added irrigation... But we also need to pay attention to where every drop of water goes—how we grade a site to direct water to tree roots, how we can capture and hold rainwater and reuse gray water... At the same time, we have to protect and grow our urban forest to provide vital shade, habitat.

j2t#098

If you are enjoying Just Two Things, please do send it on to a friend or colleague.