14 October 2023. Economics | Climate

Why there’s still a gender pay gap // Playing games to understand climate change

Welcome to Just Two Things, which I try to publish three days a week. Some links may also appear on my blog from time to time. Links to the main articles are in cross-heads as well as the story. A reminder that if you don’t see Just Two Things in your inbox, it might have been routed to your spam filter. Comments are open.

Apologies for missing an edition this week. Still a lot of work on. Have a good weekend.

1: Why there’s still a gender pay gap

I realised as I read the citation for Claudia Goldin’s Nobel Memorial Prize in Economics that I had been quoting one of her findings for years without realising that it came from her research.1 The finding was that the thing that really makes the difference to the pay gap between men and women is having children.

The Prize citation has a straightforward guide to her work, and I’m going to pull some quotes out of it, as well as one or two of their charming and very-non-technical drawings.

The first important part of Goldin’s research was just in getting the historical data straight. In general, and this will not come as a surprise, the data about women in the US labour market had tended to under-represent the number of actual women in the workforce.

She established that the proportion of women in the US labour force was considerably greater at the end of the 1890s than was shown in the official statistics. For example, her corrections demonstrated that the employment rate for married women was almost three times greater than that registered in censuses.

One of the reasons for this under-counting was that women who were described as ‘housewife’ were also in work.

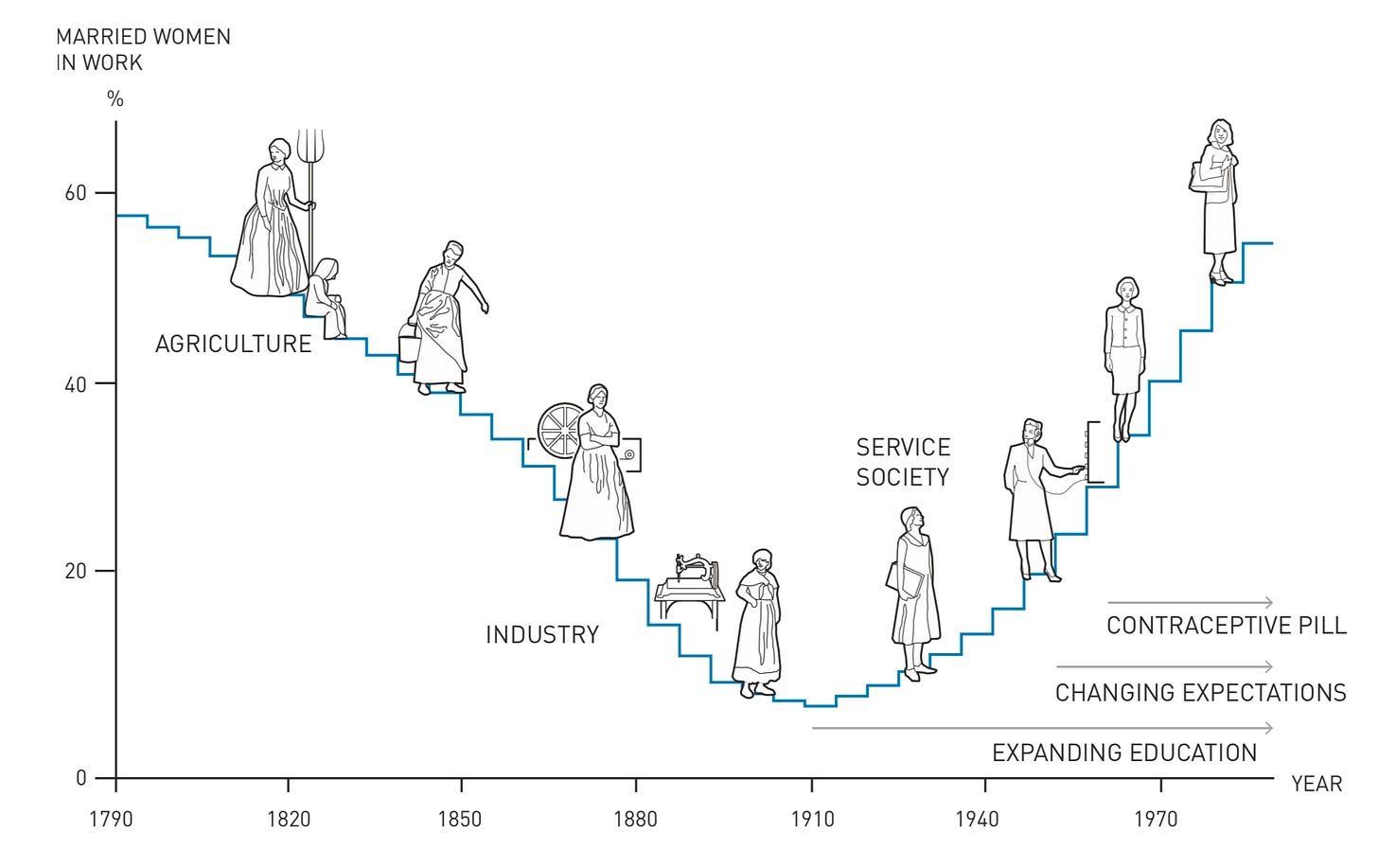

The other striking element of this historical analysis was that women were much more involved in work before the industrial revolution, and this is because pre-industrial work revolved much more around the home. Numbers then increased again as the share of services in the economy increased.

Because economic growth was steady throughout this period, Goldin’s curve demonstrated that there is no historically consist- ent association between women’s participation in the labour market and economic growth.

(Illustration: Johan Jarnestad. © The Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences)

This U-shaped curve was based on US data, but we now know that it holds for other countries as well.

At the start of the twentieth century, at the bottom of the U, the main difference between women who worked and women who didn’t was that women who worked weren’t married—20% of all women worked, but only 5% of married women. From then, the proportion of women in the workforce grew steadily, but still had the brakes on:

Goldin showed that technological progress, the growth of the service sector and increased levels of education brought an increasing demand for female labour. However, social stigma, legislation and other institutional barriers limited the influence of these factors. Goldin was also able to establish that marriage played a greater role than had previously been believed.

Part of this was down to legal issues—in some jobs women had to resign when they married. But it was also down to a set of issues around expectations. Goldin tracked different cohorts, and identified strong cohort effects during the century:

Many women who were young in the 1950s had mothers who were housewives and, when their mothers returned to the labour market, the daughters had already chosen their educational paths. In other words, the daughters did not expect to have a career when they planned their future, and it only became apparent much later that they could have one that was long and active.

What this meant was that for most of the 20th century women under-estimated how much they would work, and in effect under-estimated the value of education as a result. Their expectations only started to align with actual labour market opportunities in the 1970s, and young women started to spend more time in education as a result.

The thing that really made a difference here, though, was the invention of the contraceptive pill—simple and affordable family planning. Goldin and her co-researcher Ian Katz were able to test this because the pill became available at different times in different US states:

Goldin found that the pill resulted in women delaying marriage and childbirth. They also made other career choices, and an increasing proportion of women started to study economics, law and medicine. The affected groups were those born in the 1950s, who thus had access to the pill when they were young. In other words, the pill meant that women could better plan their future.

But: this didn’t mean that the earnings gap between men and women closed, although it did shrink. Again, the long historical data sequence going back to the late eighteenth century offers insights. For example, the earnings gap closed between 1890 and 1930, as the demand for different types of office work increased. It then stayed much the same for fifty years.

Today, the earnings gap in most high incomes countries is between 10% and 20%, even though they mostly have equal pay legislation and women are often more educated than men. Working with Katz and Marianne Bertrand, Goldin found that

initial earnings differences are small. However, as soon as the first child arrives, the trend changes; earnings immediately fall and do not increase at the same rate for women who have a child as they do for men, even if they have the same education and profession.

Studies from other countries have confirmed this conclusion:

parenthood can now almost entirely explain the income differences between women and men in high-income countries.

Obviously this has policy implications. Equal pay legislation and equal access to education is not enough to close the earnings gap. At the least, you need pathways that help women back into the workforce. These are likely to include financial help, for example in the form of affordable childcare.

But there’s also a bigger story here about how change happens. Because of the gap between finishing education and returning to work after motherhood, labour market opportunities need to be consistent with expectations over a 10-15 year period.

2: Playing games to understand climate change

I was facilitating a workshop on climate narratives this week at Chatham House—it was under the Chatham House Rule, so I can only say a little bit about it. The research that was quoted seemed to suggest that positive messages about climate narratives worked better than than gloomy ones.

In terms of deep narratives, as one of the group conversations proposed, this means moving from ‘Frankenstein’ stories (formally: ‘Overcoming the monster’) to a ‘Quest’ narrative.

These archetypes come from Christopher Booker’s book The Seven Basic Plots. On Wikipedia, ‘Overcoming the monster’ is summarised as

The protagonist sets out to defeat an antagonistic force (often evil) that threatens the protagonist and/or protagonist's homeland.

In contrast, ‘The quest’ is summarised as:

The protagonist and companions set out to acquire an important object or to get to a location. They face temptations and other obstacles along the way.

One of the things that this reminded me of afterwards was that games are often structured around quests, and in turn I was reminded of a piece in The Conversation that I’d noted during the summer, on games as a form of climate communication. It was written by Sam Illingworth of Edinburgh Napier University, who has worked across both game design and science communications:

Tabletop games (board games, card games, role-playing games – anything that can be played around a table) have a unique ability to engage players in complex systems. Experiencing a scary imaginary future in a game can inspire players to take action in the real world. Games engage our brains in a different way than just hearing news about climate disasters.

He’s also a fan of tabletop games because of the social interaction between the players while the game goes on.

Illingworth writes about a couple of games that he was involved in designing. The first one, Carbon City Zero, designed with Paul Wake, was supported by Possible:

In the game, players have to make some tough choices. Like choosing between energy sources that are cheaper right now versus ones that are better for the environment long-term. We also added event cards about topics such as misinformation and greenwashing – when companies make misleading claims about the green credentials of their products or practices while hiding unsustainable activities.

They worked with climate scientists, industry representatives and activists to make the game as realistic as they could. Players see how their decisions translate into outcomes as the game unfolds. Illingworth links this to the idea of the ‘magic circle’ in game design, a term that refers to the psychological space of the game, in which the world of game takes over from the real world. This allows players to try out different approaches and strategies within the game:

In the context of the climate crisis, the magic circle can serve as a powerful tool. It enables the simulation of climate crisis impacts and the testing of various strategies to help reduce those impacts. Games also offer unique opportunities for roleplay, allowing players to assume different characters and experience the world from different perspectives. This can foster empathy and understanding around the climate crisis.

In the same vein, I also noticed a piece in Archinect, about a competition it had run in 2016 for games similar to Monopoly that were designed to create a sustainable city rather than a bankrupt one.

In this they were perhaps channelling the pre-cursor of Monopoly, the Landlord’s Game, which was designed, famously by Lizzie Magie, a progressive woman who wanted to use games to promote the idea of Land Value Tax as a solution to landlordism.

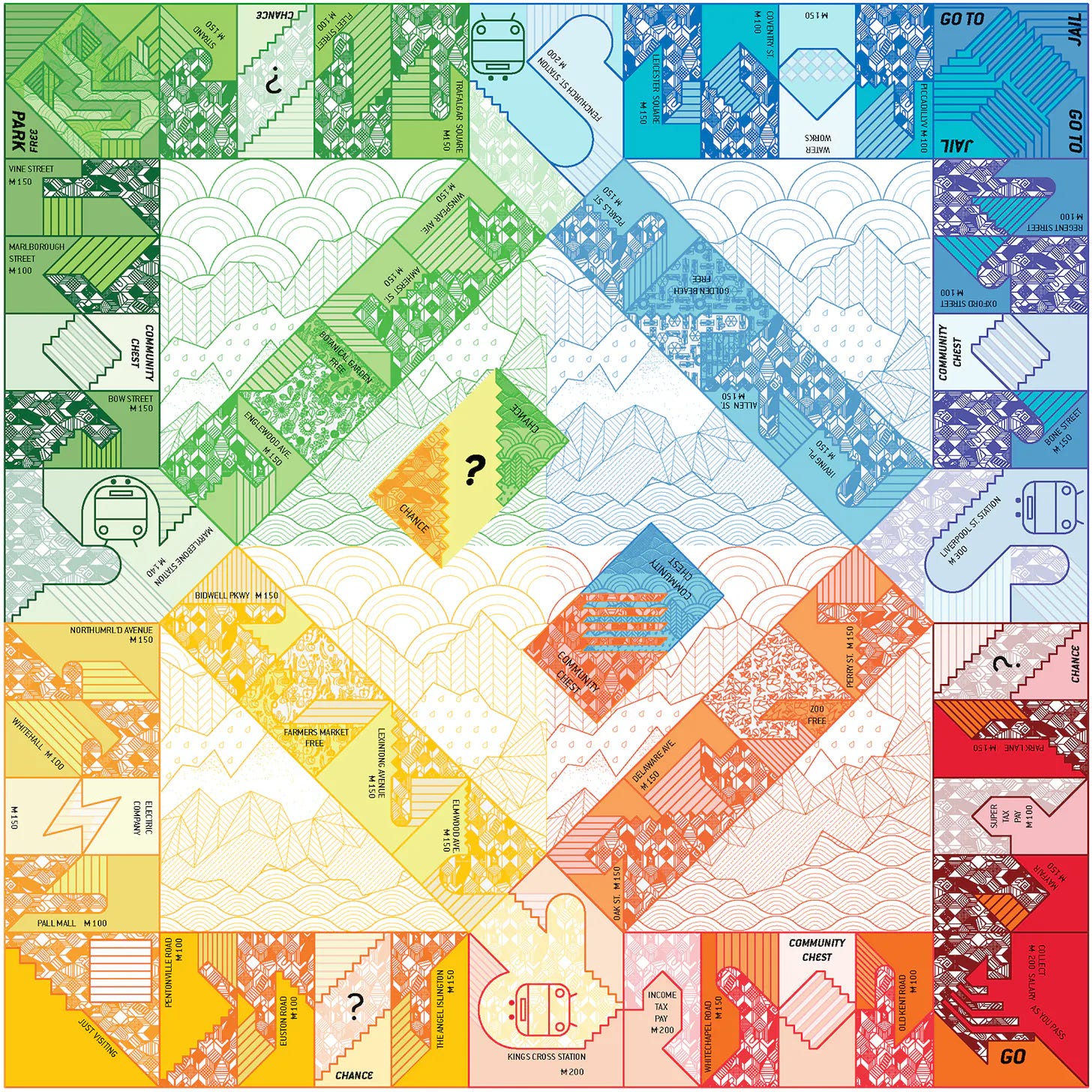

This submission by Jia Ma, styled as a kind of ecologically-conscious Monopoly, is won by creating a sustainable community, not a bankrupt one. Landlords aren't encouraged to gouge their tenants, but rather to create reasonably tiered pricing structures based on property types and their ecological amenities. As a result, properties near public transit have a higher value, and owners are encouraged to build structures that are in harmony with nature.

(ECO-MONOPOLY game board. Image: Jia Ma Source: Archinect)

In the article, Jia Ma explains the way that the game works.

Uses of a building on an owned property are no longer limited to houses and hotels. By erecting different uses of buildings on a property, the players have more choices to raise the rent. At the same time, the players should balance the benefits, and take investment risks carefully. There are four color-series on the game board and each contains three different color-groups. Like a community, every piece of property supports each other, and share benefit.

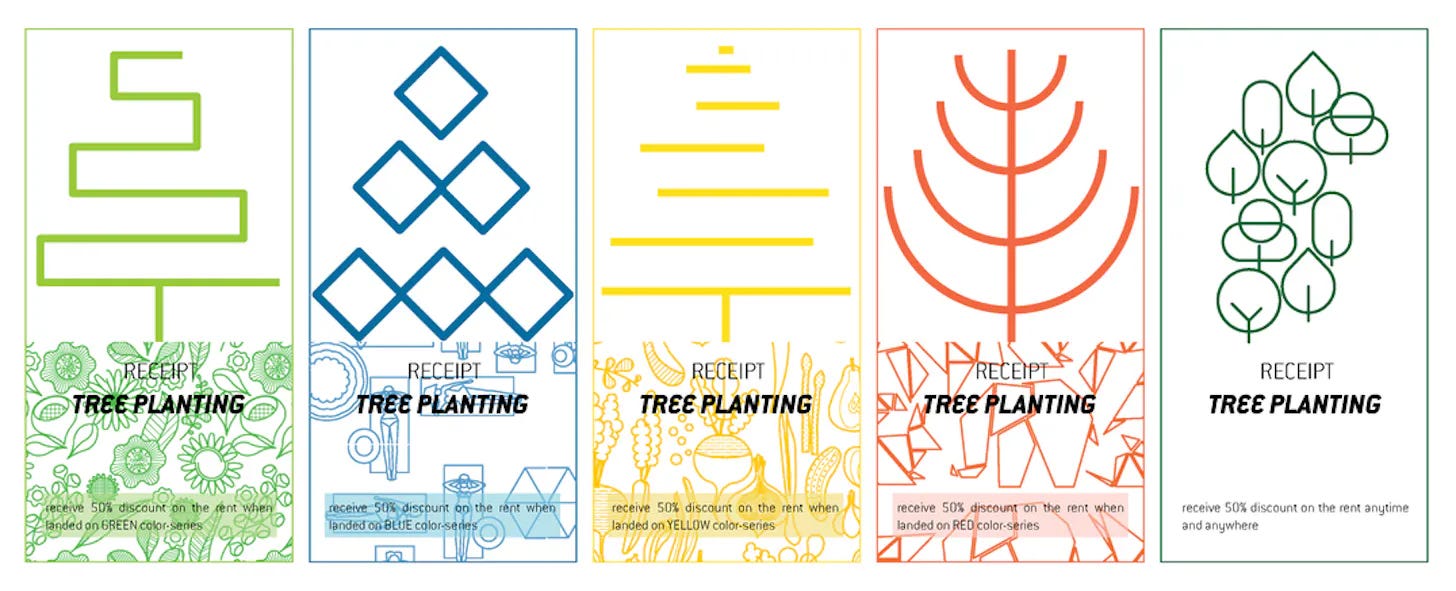

The game is designed so that houses near public transport gain in value, because of all the other benefits that brings. There are public areas of green space which are free to land on, and players get credits for planting trees. Sadly, it doesn’t seem to exist beyond her competition entry.

(ECO-MONOPOLY tree credits. Image: Jia Ma Source: Archinect)

Other writing: Red Team Blues

At my Around the Edges blog, I have a short piece about Cory Doctorow’s novel Red Team Blues. Here’s an extract:

When the plot does get properly started, Marty Hench is several hundred dollars richer, and on the run. There are people trying to kill him and Waterman Bates, from the US Department of Homeland Security, wants him to disappear with a new identity for his own safety.

And—no spoilers—the way he sorts this out is to disappear into a cash only world, living on the streets for a few days, and doing his sleuthing on the public wifi in San Francisco Public Library. But he does have a lot of cash on him.

j2t#504

If you are enjoying Just Two Things, please do send it on to a friend or colleague.

It is the Nobel Memorial Prize because the ‘Prize in Economic Sciences’ was not created by Alfred Nobel’s legacy in the late 19th century but by the Swedish Central Bank in 1968. So it is part of that process of normalising economics as a ‘science’ that has done so much damage to public policy down the years.