14 February 2025. Oligarchs | Trends

The steps to an American oligarchy // The trouble with trends reports [#630]

Welcome to Just Two Things, which I try to publish a couple of times a week. Some links may also appear on my blog from time to time. Links to the main articles are in cross-heads as well as the story. A reminder that if you don’t see Just Two Things in your inbox, it might have been routed to your spam filter. Comments are open.

1: The steps to an American oligarchy

On US election day in November I posted a piece here discussing a long interview that Fiona Hill had given to Politico on the subject of autocrats, in the United States and elsewhere in the world. Hill, who was born in the north-east of England, worked for the first Trump Administration, although I think it is fair to say that she’s no longer a fan.

Part of that interview—which I didn’t have space for then—was about the rise of oligarchy in the United States. It seems like a good moment to come back to it:

What we’ve seen in a host of other countries is that where you get an oligarchy in control, you also have a more autocratic leadership. You start to see the chipping away of the rule of law. You start to see the squeezing of the economy, as there’s deregulation in favor of particular interests and then a much more reduced space for other people to enter into the economy.

The American oligarchy

(Source: Deviant Art. CC BY 3.0)

The interviewer, Maura Reynolds, seems slightly surprised to hear Hill suggest in the interview that Elon Musk is an oligarch, and asks:

Does that mean you see oligarchy as something that’s emerging in the United States?

It’s a useful question, because it gives Hill a chance to lay out an argument that says that the United States has been on this path for a while. She suggests that between the financial crisis and the pandemic, smaller or weaker businesses went under or were bought out, resulting in greater business consolidation.1

(It’s worth pausing here to say that critics of monopolies, such as Cory Doctorow and Matt Taibbi, would also argue that weak or even compliant oversight and regulation waved all of this through, at least until Lina Khan arrived at the Federal Trade Commission.)

The billionaire owners, she notes, tend to dominate their sectors, and although this is seen as a feature of the tech sector in particular, we have also seen consolidation in sectors like food as well. Monopolies are about economic power, and although the ‘greedflation’ argument that Hill nods to is contested, there is evidence that monopolies are not good for innovation or competition.

Reynolds pushes Hill on this a bit:

People admire the business skills of Musk and Trump. Where’s the danger in having people like that holding powerful positions in government?

And since this is an argument about oligarchy, Hill makes the obvious point that in an oligarchic system power and profits become linked together.2

You get a shrinking of the economic system, and also the political system, when everything is centered around a very small class of very powerful business people and political people who are essentially fused together. The rest of us are incidental to that class of people.

There’s a bit more to all of this, and I’m going to skate over it here because I want to move on to some theory, but she also discusses the ways in which we’re seeing patterns that emerged in Russia and other oligarchies play out in the USA.

The courts get stacked in favour of the powerful; newspapers get taken over by the oligarchs and become vehicles for political influence; and that means that the media is vulnerable because those oligarchs also have contracts with the government. As we saw in the United States in the run-up to the election, even before Trump won.

From neoliberalism to plutocracy

Over the holiday period, the British economist Simon Wren-Lewis wrote a long post on his Mainly Macro blog discussing the way in which neoliberalism had morphed into plutocracy.3

Neoliberalism comes with different definitions, and Wren-Lewis’s capsule definition is this:

a collection of ideas that helps existing capital in general (e.g. reducing union power), or at least some parts of capital without harming others (privatisation).

It probably needs to be expanded slightly since these ideas are also being enforced through state agency of different kinds.

He’s interested in the post in why “why neoliberalism encourages plutocracy, and how the political right that championed neoliberalism has become plutocratic.” The way he approaches this in the piece is by examining a number of dynamics at play in this process.

Dynamic 1 is about the increasing unpopularity of neoliberalism and therefore the weaponisation of culture wars as a political strategy. Neoliberalism became unpopular because voters didn’t like the endless reductions to public services. Culture wars are a ‘look over there’ strategy designed to appeal to socially conservative voters.

But culture wars clashed with business interests—notably in the area of immigration, which led to new forms of right-wing politics, seen everywhere in the rise of hard-right populism.

Dynamic 2 is about a growing dependence on wealth and the media. Perhaps paradoxically, when the right splits, the wealthy, and media owners, who are often the same people, have more chance to play different groups off each other to get the policy outcomes they want.

Dynamic 3 is the drift of centre and centre-left parties away from neoliberalism, albeit too slowly for their own good. Unlike the shift in Dynamic 1, this is for economic reasons, to do with the failure of neoliberal economics to deliver good economic outcomes, as well as political reasons (their voters also hate endless reductions in public services).

Wren-Lewis suggests that:

In this new landscape, the central political fight is between right wing socially conservative populists serving the interests of a select plutocracy, and more traditional centre or centre/left parties generally triangulating on culture wars but pursuing an economic policy that is a blend between neoliberalism and more traditional social democracy.

All the same he is puzzled as to why centre/left parties don’t make more of the plutocracy that sits behind populist parties.

At an economic level, as we’re seeing in the United States, this makes policy unpredictable—deregulation and tax cuts, certainly, but not in ways that enable the kind of stable environment that most business prefers.

One of the costs of this, though, is that it turns politics into a competition for the support of different fractions of capital, as we see with the Democrats in the United States and the stuttering obsession of the British Labour party with ‘growth’, whatever that is supposed to mean, and of not offending business interests. The public interest somehow gets lost in this competition, and this means that their political base becomes increasingly fragile—and vulnerable to the populist right.

Reactionary tech bros

This question of where different sections of capital place their bets is the subject of an article by John Ganz at Unpopular Front which takes a more or less Marxist view of the emergence of Silicon Valley’s more reactionary billionaires as Trump’s financial vanguard. This is, as he says, the key difference between Trump 2016 and Trump 2024. His piece has, I think, quite a lot of explanatory power, so I’m going to give it some air here:

[H]ere’s what I believe happened: In the process of accumulating enormous wealth, the tech-oligarchs created the conditions for their loss of social power and, when they realized this, they got a big dose of class consciousness and turned furiously reactionary.

Capitalism always creates its own contradictions. It’s a long piece, and quite dense in places, and I’m not going to be able to do more than sketch it out briefly here, but in this case, he argues that the contradiction worked like this.

As in the nineteenth century, new technology created new social relationships. In Ganz’s account, the internet accelerated the growth of progressive ideas among people whose work had been made more precarious by the same digital technologies:

the great demonstrations of early Trumpism, #MeToo, “wokeness,” the new wave of labor activism, the shifting nature of gender relations, and, ultimately, the big one, the George Floyd protests were all different articulations of the progressive counter-thrust.

And the labour force of the big technology companies were more radical than their owners were.

We don’t don’t need to take Ganz’s word for it. As he points out, the tech billionaire Marc Andreesen told Ross Douhat exactly the same story on a podcast recently:

[T]he kids turned on capitalism in a very fundamental way. They came out as some version of radical Marxist, and the fundamental valence went from “Capitalism is good and an enabler of the good society” to “Capitalism is evil and should be torn down.” And then the other part was social revolution and the social revolution, of course, was the Great Awokening, and then those conjoined.

You can feel his pain. But when people say things on the record to sympathetic interviewers, they are as likely to be telling the truth as lying.

The result of this was a change in the worldview of Silicon Valley. Their business models have changed as well—away from consumer-oriented social and digital media to industrial and military technology.4

This isn’t just politics. If you’re a fan of Carlota Perez’s techo-financial long waves model, these companies are at the end of their 50-60 year wave, and it is getting harder for them to make money. Hence “enshittification”, a word of the year in 2023.

And so, their espoused politics have shifted through 180 degrees, as Ganz describes (emphasis in the original):

To save themselves, the tech-oligarchs must attack the very notion of universality as such—hence their abandonment of liberal universalism for racism, nationalism, masculine domination, etc., because they represent a conspiracy, a shrinking, exclusive interest against a larger one. They are attacking first and foremost the State and the Bureaucracy, the civil servants: everything that Hegel identified in The Philosophy of Right with the universal, general interest of the whole society.

(Guerrilla Girls, ‘President Trump Announces New Commemorative Months!’, 2016. Photo: Hrag Vartanian. Via Hyperallergic.)

Elon Musk and Peter Thiel are the obvious exemplars here. Their politics have always been a long way to the right—despite Musk’s fortune being founded on large public subsidies. But it is also striking how quickly the mask slipped elsewhere. Zuckerberg goes on Joe Rogan’s show and blahs about ‘masculine energy’, while some poor Google spokeswoman has to dissemble on why Black History Month, Women’s History Month and Pride Month are being removed from its calendar, and still look at herself in the mirror in the morning. As Ganz observes:

Musk’s total idiocy is structural: it goes back to the very origin of the Greek term idiotes, a person who cannot understand the shared political life of the city.These people cannot understand that their wealth and power are not their sovereign creations but the shared product of the wider state and society that supports and sustains them. [Emphasis in original).

The question about counter-revolutions such as this is: will they stick? This was probably the last chance they have to stage such a counter-revolution—the circumstances of Trump’s Teflon candidacy and his second Presidency are unlikely to be repeated. But Ganz thinks they have struck too soon. Maybe the spectacle of automated everything through AGI is more than just a fable.

Because right now, the forces of technology production still need people to help accumulate their wealth, as we see from the cheap back office labour that props up large language models and their regular insistence that their staff need to be physically in the office five days a week.

One of the things that all of this reveals is that the dystopian world in which AIs have taken our jobs and left us all destitute is not so much a scenario which needs endless public policy discussion. Instead it is the return of the repressed. It’s the story that our tech billionaires wish for, but still have to pretend that they don’t.

2: The trouble with trends reports

Matt Klein spent some time for a product he calls METATrends analysing a lot of trends reports, and in an entertaining and trenchant article he calls many of them as bullshit. In fact, he’s not that keen on the whole cult of trends at all. They are supposed to help reduce uncertainty, he argues, and offer “a map, a compass, and a thermometer”. But:

the vast majority of our trend fodder today does not help us in our pursuit of judiciously navigating change. Instead it pumps hype and entertains us, dialing up the existing, deafening noise which we’re tasked with listening to. As cultural researcher Victoria Buchanan points out, perhaps this is reflective of the much larger shift in the “junk-ification of our information.”

In fact, the number of trends reports published has doubled in five years, to around 250, which is clearly a trend in itself. But less than half of these have a published methodology, and fewer have a methodology that you’d want to defend. Most of them serve as corporate advertising. It’s also hard to tell what’s new:

Last year I asked 200 strategists around the world if they could distinguish between trends published from 2018 or 2024. Turns out you were better off guessing 50-50 than actually trying to discern the difference. The experts can’t tell when something was published six years apart.

Trends reports tend to come out every year. But as Klein observes, culture has a clock speed that is slower than that. So we end up with a “cult of the new” (my phrase, not his) rather than trying to understand what’s actually changing. Trends reports end up repeating themselves.

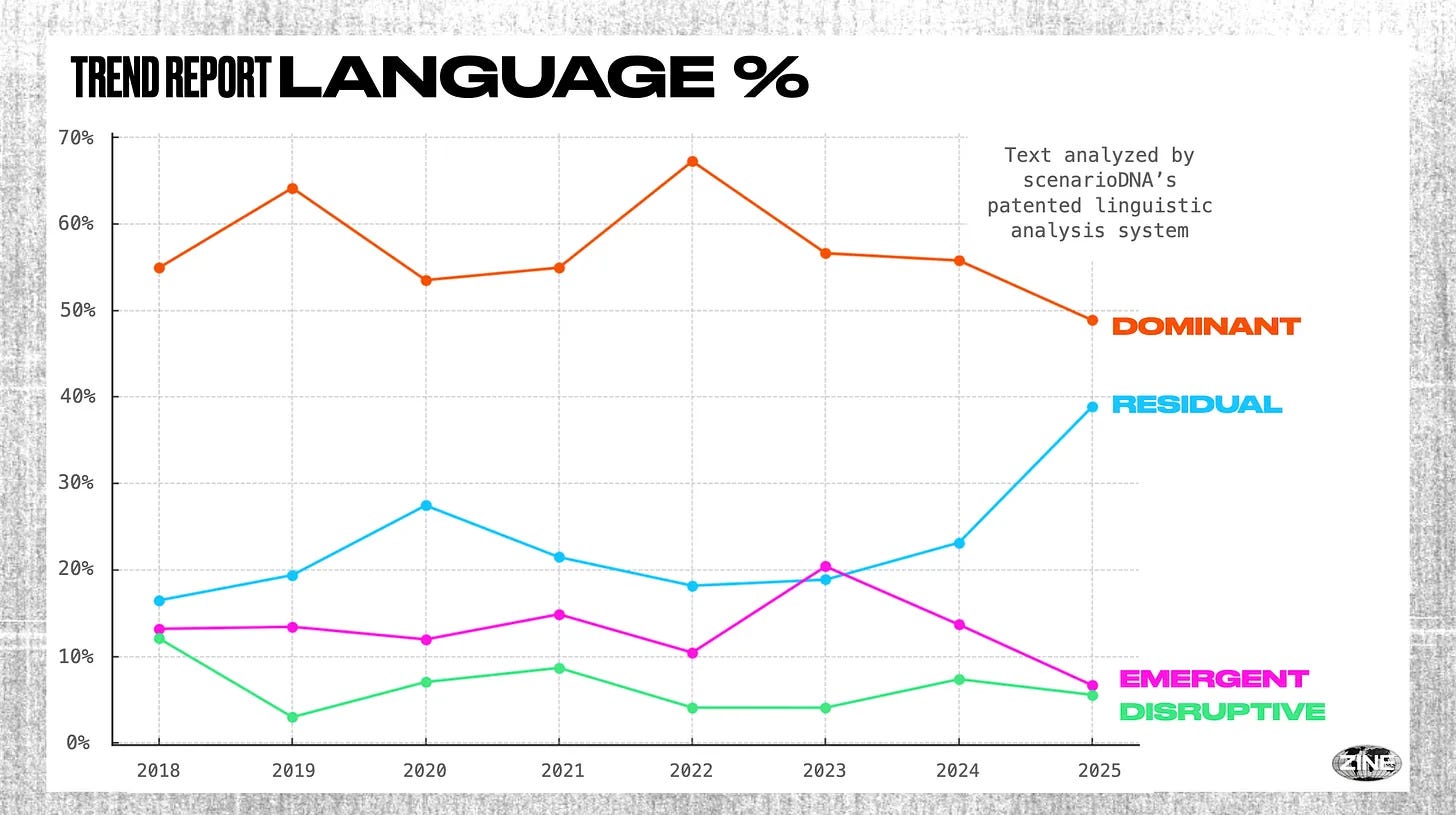

He did some research to test this hypothesis, partnering with a cultural analysis agency, scenarioDNA, and feeding eight years of trends data into their Culture Mapping tool, which uses semiotic analysis to map phrases into one of four language quadrants. These are: Residual, Dominant, Emergent or Disruptive.

Most of the several thousands of pages they fed in came out as ‘Dominant’ or ‘Residual’, as seen in the chart. It looks to me as if, broadly, the share of Emergent and Disruptive is trending down slightly. This might be a reflection of new entrants with nothing to say. Because: it is hard to say much that is interesting about trends. I worked for a business that did a regular trends report in the early 2000s, and identifying material that was both new and interesting was difficult work.

(Source: Matt Klein)

He has another theory. Most trends reports cover only 10 cities worldwide, and they are exactly the cities you’d expect: London, New York, Tokyo, Paris, Shanghai, Los Angeles, Amsterdam, Berlin, São Paulo and Seoul. It sounds like an 80s electropop track.

This grim, uninspiring lack of global representation, in combination with a lack of rigorous let alone quantitative analysis or external collaboration + toxic positivity + fear of risk, reflection, and realism + industry peacocking + commercial bias, ultimately prevents trend reports from ever reaching their fullest potential value: judiciously navigating our change.

Does it matter? Does anyone take trends reports seriously? Mostly they’re read by marketing professionals who need to look a bit smarter in meetings.

Klein thinks it does. Partly because he has a data point from an agency that says that 150 trends reports got 14 billion online impressions globally. Although I’m not sure what the time period is there, that’s a lot of time and attention on sub-standard products.

He does have three tips on how to get more interesting perspectives on emerging futures, which I think I can summarise as “get out more”, “think a bit harder”, and “get some skin in the game”.

I’ll pull three quick quotes from this part of the article:

01. Talk to Others

We need to get out of our own heads and into conversation with others. When I advise “fringes are the future and we must seek the overlooked,” that’s not just the underground, subversive and unknown, but — more simply — voices and markets not represented.

02. Seek Edges & Narratives

In network theory, diagrams visualize dots (“nodes”) and the lines which connect them (“edges”). Combined, they create maps: What’s connected to what?

In our work, these clusters of nodes are our “trends.” The more clusters of signals of change we collect, the more clear our view is...

Lines are our narratives — stories of change.

He quotes the cultural anthropologist Grant McCracken:

We want a concept of change, a theory of change, a search for the meaning and mechanics of change. Only thus can we get better at reading change.

03. Pollinate & Seed Futures (Responsibly)

When you’re an active participant in the interests of those you hope to resonate with, you don’t need to decode what’s trending. You’ll know. Therefore, you — especially you with an interest in trends — have a responsibility to play, crafting what you believe is needed.

But that responsibility also comes with a responsibility. If you’re going to insert yourself into systems—which is what you’re doing when you craft “what you believe is needed”—you have become part of that system. And doing that also requires ethics.

All the same, doing any of these things, let’s face it, is better than reading a trends report.

j2t#630

If you are enjoying Just Two Things, please do send it on to a friend or colleague.

The legal groundwork was laid in 2010: “We’ve got an American system that because of Citizens United — which I think is one of the most consequential Supreme Court decisions in our lifetimes — has become a political system that’s driven by money.”

Robert Reich has spelled out how this has worked for Musk since Trump became president. Musk is $270 billion richer (this is not a typo) than he was before the election because dozens of Federal investigations into wrongdoing at his companies have been closed down.

Or this, from Heather Cox Richardson’s now essential daily blog on 12th February: “As both the New York Times and the Washington Postreported today, the big winner from all the cuts to the government has been Musk himself, who has eliminated the agencies that were scrutinizing his businesses.” The $250 million he paid to finance Trump and other GOP candidates during the election suddenly looks like chump change.

Wren-Lewis has a footnote on the distinction between plutocracy and oligarchy: “I prefer plutocracy to oligarchy because it stresses the key point that political leaders are either very wealthy themselves, or answer to those who are.” If you’re on the receiving end of either of these the distinction may seem less important.

Incidentally, one of the things about consumer-facing businesses is that they need to some extent to reflect the people who are their users and customers—they don’t wander too far from the mainstream.

Agree on the trend report diagnosis and I appreciate the proposed remedies. Increasingly, I wonder whether the foundational assumption of futures studies—that the future is embedded in the present—is in fact all that useful (or is just banal), because the hard part is figuring out how to act in complex contexts where, depending on your aperture, the signal is nearly impossible to discern from the noise.

Brilliant - both components quite brilliant. Thank you