13 October 2021. Land | Cars

Returning land to indigenous peoples; the material impact of electric cars

Welcome to Just Two Things, which I try to publish daily, five days a week. (For the next few weeks this might be four days a week while I do a course: we’ll see how it goes). Some links may also appear on my blog from time to time. Links to the main articles are in cross-heads as well as the story.

#1: Returning land to indigenous peoples

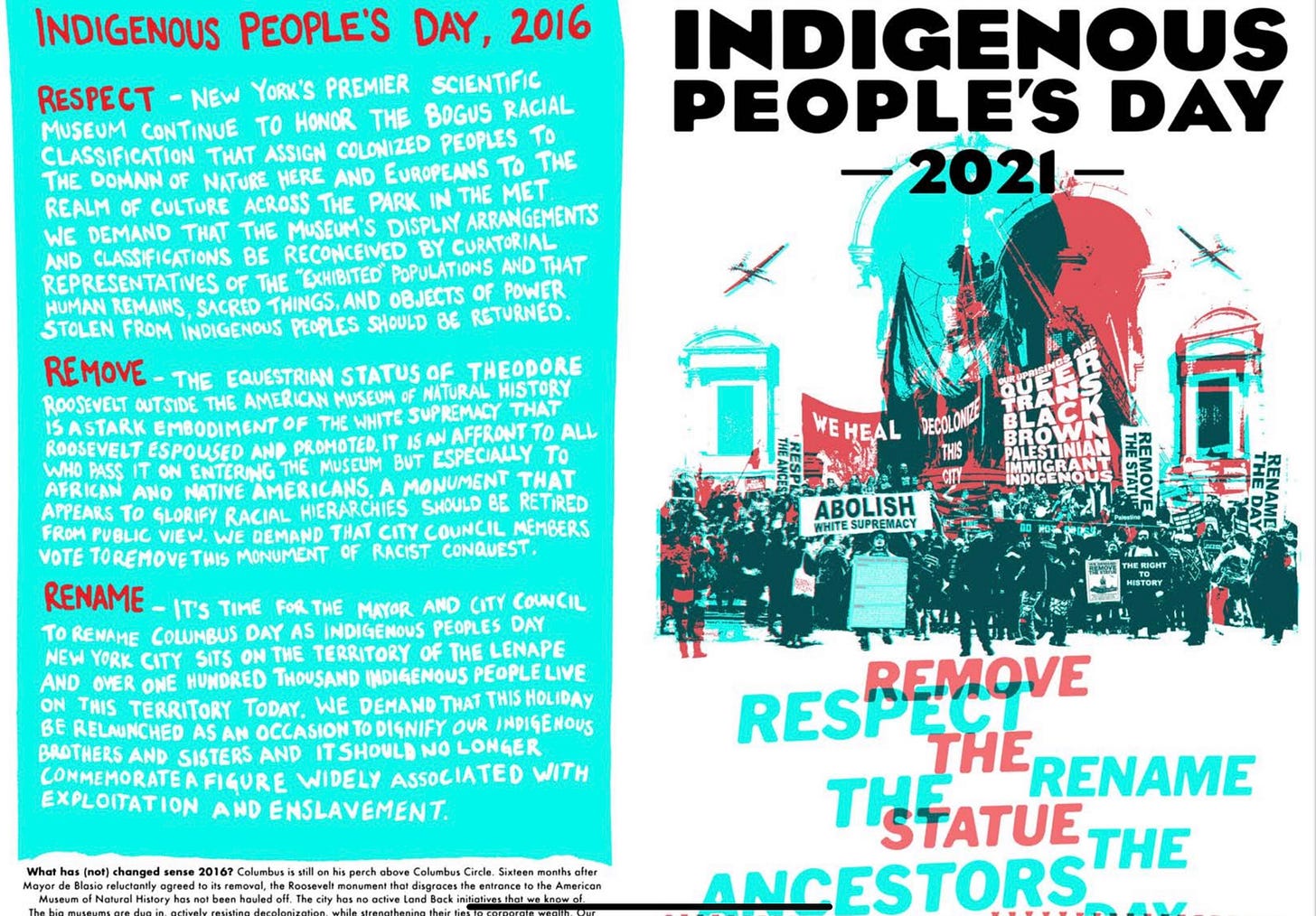

I’m short of time today, so I’m going to note quite quickly that Monday was Indigenous People’s Day in the United States, covered by the arts website Hyperallergic. The day is designed to honour the history, culture and indigenous struggles of the indigenous peoples of the USA, and as its impact rises, that of Columbus Day—which also falls on the second Monday in October—is in decline.

In some places in the US, states and public organisations are choosing not to honour Columbus Day, though not without some missteps.

To mark the occasion some statues were doused with red paint—including that of President Theodore Roosevelt flanked by subservient indigenous peoples. It sits outside New York’s Museum of American Natural History, and the museum has been promising to remove it for more than a year.

The arts activist group Decolonise This Place—responsible for the protests earlier this year at MOMA—published a zine to mark the day. These screenshots come from this, and I have to say I love the urgent screenprint aesthetic of all of these.

(Source: Decolonizethisplace.org)

One of the outcomes of these indigenous peoples’ protests has been to force organisations—notably museums—to acknowledge that they are built on land stolen from indigenous peoples. This is known as a ‘living land acknowledgement”, and the New Museum in New York became this week the most recent museum to make such an acknowledgement, that it was built on land that was unceded by the Lenape peoples.

This is probably best regarded as a step in the right direction. That seems to be the view of Joe Baker, the executive director of the Lenape Center, which helped the museum draft its statement:

It’s up to the organization to create their own living land acknowledgment but we encourage them to come up with actionable steps that they will take toward a more equitable future and addressing this genocide.

In all of this, as Hyperallergic notes, the US lags behind countries such as Canada, Australia, and New Zealand. Other views about the value of such statements are also available, as the article also points out:

But as long as these statements avoid addressing the issue of returning the land to its original owners, they will remain hollow and useless, according to Joseph Pierce, an associate professor in the Department of Hispanic Languages and Literature at Stony Brook University and a Cherokee Nation citizen...

“A statement that stops at a land acknowledgment is detrimental to the return of Indigenous people to their land,” Pierce explained. “Cultural institutions are trying to ride the decolonial wave but they’re missing one thing: decolonial practice is not about what you say and what you know — it’s about how you do things.”

#2: The material impact of electric cars

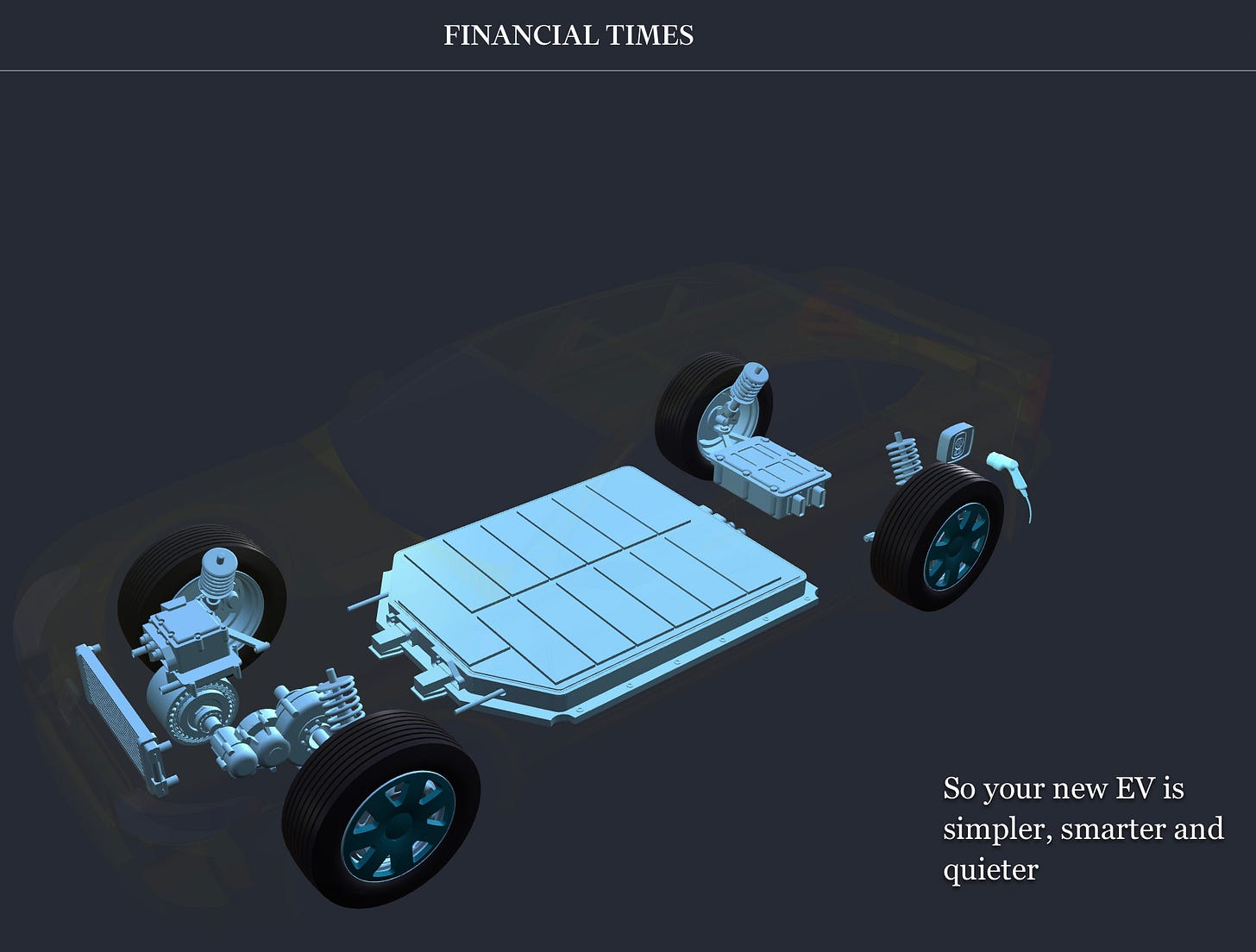

There’s a fabulous piece of visual storytelling in the Financial Times on the subject of electric vehicles that also seems to be outside of the paywall. (My thanks to Nick Wray for alerting me to it.) This screenshot conveys an idea of the style.

Given the format, it’s not easy to quote from the piece, but let me pull out some highlights about the environmental friendliness, or not, of electric vehicles:

- “Before it leaves the factory your new EV is responsible for a large volume of carbon dioxide emissions — far more, in fact, than the petrol car you just traded in

- “One study in China suggests the CO2 produced when making an EV is 60 per cent higher than from combustion models”

- A lot of this is down to the battery—which may be easier to make than a piston-driven petrol engine, but it uses some dirty materials. These have to be mined and smelted, sometimes in questionable conditions

- And mining produces a lot of CO2

- Then they have to be transported

- And then they have to be assembled, which is also energy-sapping: “Nissan’s new battery factory in Sunderland will require its own £80m power grid”

- All of that is before it leaves the dealer’s forecourt

- When you drive it, how green it is depends entirely on how green the electricity supply is

- And then there’s the question of what to do with the battery at the end of its life, although this might be a solution to a different transition question—of how to store electricity produced locally rather than overload the grid.

- Not forgetting the pollution from the tyres, which is greater than an equivalent petrol driven vehicle because EVs are a little heavier.

But despite all of that, EVs are already a lot cleaner than petrol driven vehicles across their whole lives:

A 2021 study by the International Council on Clean Transportation estimates that with today’s power plants providing the energy the emissions from an EV across its whole lifecycle — from manufacturing to miles on the road — are 66-69 per cent below those of petrol cars in Europe.

And this gap gets wider as renewable energy starts to produce more of our power.

j2t#186

If you are enjoying Just Two Things, please do send it on to a friend or colleague.