13 March 2023. Tech | Refugees

The ‘enshittification’ of the corporate world. // Letting refugees work.

Welcome to Just Two Things, which I try to publish three days a week. Some links may also appear on my blog from time to time. Links to the main articles are in cross-heads as well as the story. A reminder that if you don’t see Just Two Things in your inbox, it might have been routed to your spam filter. Comments are open.

1: The ‘enshittification’ of the corporate world

When it comes to regular newsletter writing, I am in awe of the Canadian writer, researcher and tech activist Cory Doctorow, who manages to produce long, detailed and carefully linked articles five days a week at his Pluralistic blog.

Now it seems that he has managed to add a neologism to the language, even if it is both ugly and memorable, to describe the business processes of tech companies over time. This is the word “enshittification”. Well, as I sad: ugly and memorable.

The phrase appeared first, I think, in a column that Doctorow wrote for Locus at the start of the year (it might have been earlier, since he is so prolific it is hard to keep track). The column dealt with the life cycle of technology companies. He was specifically interested in the exodus of users from Facebook and Twitter, although he has applied the model to TikTok and Amazon since then as well.

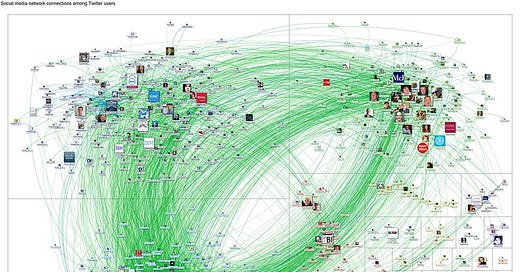

(Marc Smith, 20120227-NodeXL-Twitter-bigdata network graph, via Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

The argument goes like this. Successful social media companies enjoy network effects: the more people are on it, the more other people want to be, or need to be, on it. Network effects are exponential in their effects, because of the way the number of possible connections increases as more people join.1 But when people leave, this process goes into reverse.

One of the reasons why people don’t leave is because of ‘switching costs’. In social networks these costs are almost all social costs: you can’t access groups of friends you used to be able to access, for example. As social media companies have got more sophisticated (I don’t mean ‘sophisticated’ in a good way) they have learned new ways to make it more difficult to leave.

So, in short, the underlying logic of a social network is to make it as easy as possible for people to join—and as hard as possible to leave:

as Facebook and Twitter cemented their dominance, they steadily changed their services to capture more and more of the value that their users generated for them. At first, the companies shifted value from users to advertisers: engaging in more surveillance to enable finer-grained targeting and offering more intrusive forms of advertising that would fetch high prices from advertisers.

This is the process of ‘enshittification’. And in the process, the value proposition changes. The companies become takers rather than makers. In his later article in Wired, on TikTok and Amazon, he had got this story down to a crisp few lines:

Here is how platforms die: First, they are good to their users; then they abuse their users to make things better for their business customers; finally, they abuse those business customers to claw back all the value for themselves. Then, they die.

The particular business models that have underpinned the digital tech sector have sharpened this process. Venture capitalists don’t worry too much early on about profits, or even revenues: what matters is user numbers and user growth. But they do later. Or they want to get their money back through a sale or a stock market flotation (IPO).

Perhaps not by chance, Doctorow’s neologism has had some airplay elsewhere recently. John Naughton mentioned it in his tech column in the Observer. And Tim Harford discussed it in a recent Undercover Economist (paywalled?) Financial Times column. And this whole process may also reflect that the tech sector is now a mature sector, with limited (or no) opportunities for growth from acquiring new customers, and therefore it starts to behave more like the rest of the economy.

In Techdirt in January, Mike Masnick suggested that this was a problem that extended beyond the tech sector. He traced it back to Milton Friedman’s assertion that the only duty of a company was to return value to shareholders. As a business model we know that this isn’t sustainable:

maximizing revenue in the short term... often means sacrificing long term sustainability and long term profits. That’s because if you’re only looking at the next quarter (or, perhaps, the next two to four quarters if we’re being generous) then you’re going to be tempted to squeeze more of the value out of your customers, to “maximize revenue” or “maximize profits for shareholders.” That’s because “Wall Street” and the whole “fiduciary duty to your shareholders” argues that if you’re not squeezing your customers for more value — or more “average revenue per user” (ARPU) — then you’re somehow not living up to your fiduciary duty.

So this is about the conflict between companies with extractive business models, and companies with productive business models—locusts and bees, as Geoff Mulgan once called them.

Masnick quotes the tech publisher Tim O’Reilly in the same vein:

Tim O’Reilly has (correctly) argued that good companies should “create more value than they capture.” The idea here is pretty straightforward: if you have a surplus, and you share more of it with others (users and partners) that’s actually better for your long term viability, as there’s more and more of a reason for those users, partners, customers, etc. to keep doing business with you.

As Masnick and O’Reilly observe, this problem is more about the financialisation of the corporate sector than it is about particular characteristics of the tech sector (although the particular characteristics of the tech sector certainly help.)

I was reminded of Doctorow’s article because I was interested in the way that private equity companies squeeze the businesses they acquire to achieve efficiencies and increase returns, because I’d had a bad experience recently with a formerly family-owned business that had been acquired by private equity. It had become more interested in revenues and returns, and less interested in the quality of experience of its customers.

I might come back to private equity in another piece, since I think its significant role in the British economy (and the American) may be one of the reasons for productivity crisis in the UK. Because: if investors expect 5%-plus returns in a 1-2% growth economic environment, this is more likely to lead to extraction than investment. The reason: investing for growth is harder, less predictable, and takes longer to generate returns than cutting jobs and services.

In other words, the diagnosis of ‘enshittification’ is right on the money. But the disease is far more widespread, and goes far deeper, than Doctorow suggests.

2: Letting refugees work

At the New Humanitarian, Matai Muon, a South Sudanese refugee who has spent time in Kenya and is now studying for an M.Phil at Oxford, has a radical idea about improving outcomes for refugees: let them have access to work.

Because right now, more than half of refugees worldwide have their access to work restricted:

Refugees are often depicted as economic burdens on the communities where they have found safety, and on the international aid system. This overlooks the fact that 55% of refugees live in countries where their right to work and fully participate in society is restricted.

And just to be clear, Muon is writing about his experience in Kenya. But he might as well be writing about the UK:

This suppression of refugees’ economic freedom and potential forces many of us into a state of dependency, turning the narrative of economic burden into a self-fulfilling prophecy.

Unlike the UK, Kenya has more than half a million refugees, from Somalia, South Sudan, Ethiopia and Burundi, and most are housed in two large camps, Kakuma and Dadaab. These are largely dependent on international aid.

(Dadaab camp from the air. Oxfam International. CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

As it happens, Kenya changed the law last year to make it a bit easier for refugees to work. There are still obstacles: they need to travel to Nairobi, they need documentation, they need to have their qualifications recognised by the relevant Kenyan bodies, for example. But it’s a step in the right direction:

My own experiences and my work with urban refugee entrepreneurs in Kenya’s capital, Nairobi, have shown me that a different reality is possible: Many refugees are brimming with creative ideas, energy, and a desire to be active economic agents – able to provide for ourselves while contributing to our host country’s economy – if only we are given the chance.

Muon tells the story of his own difficulties in getting access to education in Kenya, which involved staying outside of the camps and being harassed by police. Even when he was close, he needed to be able to get a South Sudanese passport at a time when South Sudan was not independent:

All of these complications, I believe, were a deliberate way of trying to discourage refugees from coming to Kenya. And they were just a small sample of the barriers refugees face in day-to-day life... But the fact that Kenya’s laws and bureaucracy have historically excluded refugees from the labour market does not mean that refugees do not have economic potential.

Of course, Britain has a tiny refugee population compared to Kenya, and has much stricter laws that prevent those from seeking asylum from working. This is a consequence of the former Home Secretary Theresa May’s notion of the ‘hostile environment’, which at a rhetorical level pretends to discourage refugees from coming to the UK. Who knows? Perhaps she dreamt it up while walking to church one Sunday.

One of the problems with all of this discourse is that it is driven by a zero-sum view of economics, that migrants take jobs rather than helping to lift the tide so that all the boats rise.

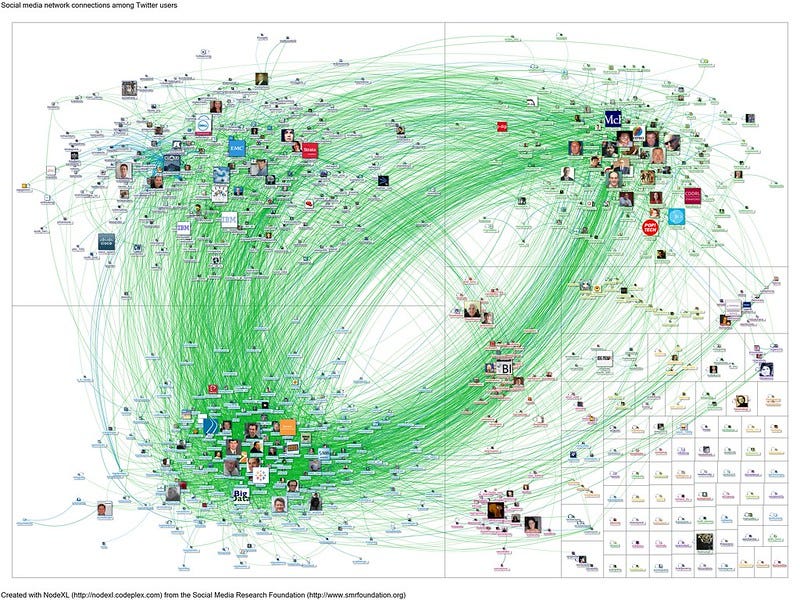

As it happens, I was going to write about this piece before the row broke at the end of last week about Gary Lineker’s twitter criticism of the British government’s new and probably unlawful Illegal Migration Bill. (For non-UK readers, Gary Lineker is a presenter of the BBC’s flagship football—soccer—programme, and formerly an outstanding player. If you want to skip the local British section that follows, please do).

(The Illegal Migration Bill. Annotated by Robert Peston on Twitter)

As a result Lineker was, in effect, suspended from presenting Match of the Day by a BBC management that said he had breached its impartiality guidelines, but is also too close to the government for its own good. (The current BBC chairman had donated £400,000 to the Conservative Party, and helped to arrange an £800,000 loan to the former Prime Minister, Boris Johnson: the current Director-General was the deputy chair of a local Conservative party in the 1990s and stood as a councillor.)

Lineker has some history in speaking out on behalf of refugees. A couple of years ago he fronted an entertaining short video about the British staple, fish and chips, for the International Rescue Committee UK:

But that didn’t involve speaking out against some high profile and controversial Government legislation. All the same the BBC was completely wrong-footed by the response to its suspension decision, which involved pretty much all of his colleagues involved in the BBC’s football coverage declining to work on Saturday.

So what’s going on here?

From the BBC point of view, for all its complex arms-length funding relationship with the government, it has always been close to governments of the day. This goes back to the General Strike in 1926, when it was still the British Broadcasting Company, when the BBC was not impartial between government and strikers. As the Managing Director John Reith said in his diary:

The Cabinet... want to be able to say that they did not commandeer us, but they know they can trust us not to be really impartial.

Reith was certainly a Conservative, but he understood the importance of appearances. With a current chairman who is so close to the Government this has vanished.

But the second part of this is the expression of solidarity among other sports presenters. This seems to have astonished the BBC’s management. If they thought it through—and they might not have thought it through—I think they saw this well-paid group as atomised individuals who would look after their self-interest, even their financial interest. But most of them come from working class backgrounds, and many of them are black. It’s possible that their experience of the hostile environment, in policing and the Border Force, is different from that of the affluent white men at the top of the BBC.

But this whole story also tells us something of the state of contemporary Conservatism. It has no story any more, certainly no positive story. All that is left is othering, performative gestures, and the politics of culture wars.

((C) Cold War Steve)

j2t#435

If you are enjoying Just Two Things, please do send it on to a friend or colleague.

The best mathematical description is n(n-1)/2, which is the number of connections or vertices in a network with n nodes.

re: topic 1, Chris Dillow wrote this today: https://stumblingandmumbling.typepad.com/stumbling_and_mumbling/2023/03/technical-regress.html about how it applies more generally to the UK economy