12 October 2024. Weather | Law

Cleaning up after hurricanes //. Understanding the Nakba through a legal lens. [#607]

Welcome to Just Two Things, which I try to publish two or three times a week. Some links may also appear on my blog from time to time. Links to the main articles are in cross-heads as well as the story. A reminder that if you don’t see Just Two Things in your inbox, it might have been routed to your spam filter. Comments are open.

1: Cleaning up after hurricanes

As Hurricane Milton follows hard on the heels of Hurricane Helene, it’s worth noting some of what’s happening here in terms of the change in the weather. We’re not getting more hurricanes because of climate change, but they are becoming more intense because of climate change.

The Verge analysed why Helene became so powerful. The hurricane has killed more than a hundred people, and devastated some inland parts of North Carolina. It took power out for millions of people:

[I]t’s clear that the storm was disastrous because of its unusual size, intensity, and speed. The perfect conditions were in place to supercharge the storm.

In the first place Helene was unusually large.

At its maximum, tropical storm-force winds extended nearly 350 miles away from Helene’s center. That enormous reach put Helene in the 90th percentile for storm size, according to the National Hurricane Center.

This meant that when the storm hit landfall, its effects were felt over an unusually wide area.

Second, it was much stronger than most hurricanes. Helene had a small eye that intensified rapidly. Windspeeds were 140 miles an hour (225kph) when it reached the coast, and the storm was travelling at 20-30 miles an hour (30-45kph) across the ground, twice as fast as aa average hurricane. This also meant that it travelled further inland.

And third, it picked up a lot of water:

When it hit Florida’s Big Bend region, it brought a massive storm surge, inundating the coastline with up to 15 feet of seawater. The underwater topography off Florida’s west coast, with a more gradual incline, acted like a ramp, making it easier for the storm to bring a taller wall of water with it. The sheer size of the hurricane also meant that the storm surge flooded a wider area.

We won’t know for a while how much of this impact is down to climate change, but there are already some clues.

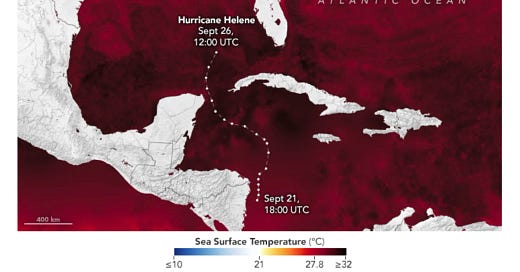

Rising global temperatures create conditions conducive to more intense storms that can gain strength quickly and stay more powerful onshore... Waters along the storm’s early path got as high as 31 degrees Celsius (87.8 degrees Fahrenheit), providing ample fuel. The atmosphere’s ability to hold moisture is increasing because of greenhouse gas emissions from fossil fuels, allowing for more severe downpours.

(Sea surface temperatures on September 23rd. Image: NASA Earth Observatory)

Karthik Balaguru, a climate scientist at the Pacific Northwest National Laboratory,

likens the effect of climate change to the world having a weakened immune system. “It doesn’t mean that you will become sick. It just increases your tendency to become sick,” Balaguru says.

In summary, then, as explained by John Knox of the Atmospheric Sciences Program at the University of Georgia:

“The storm started big, which was bad, it went over hot water, which was bad, it hit a place that is prone to high storm surge, and then it accelerated and went into populated areas and took wind and rainwater to those populated areas,” Knox says. “You don’t want to see much worse.”

At the Naked Capitalism blog, Yves Smith pointed out some revealing comments from an interview with the former FEMA [Federal Emergency Management Agency] director Brock Long, as quoted in the Atlantic. And not in a good way.

Long basically said that when the communications networks were down FEMA didn’t know what to do because it wasn’t getting information from the affected communities. Smith was surprised by this:

The model is officials wait for demands for help and complaints to come in?!??! That might have been the best you could do 20 years ago, but has no one heard of drones?

Long also suggested that FEMA represented ‘top-up’ response capability, covering where local and state jurisdictions didn’t have enough capacity. Yves Smith was surprised by this as well, since people affected by the storm clearly expected FEMA to take the lead.

The same Naked Capitalism blog post included a firsthand account from a friend in North Carolina on the experience of responding to the damage caused by Helene. There was some improvisation: without power in the house he discovered that he could charge his phone from his car by letting the engine run in ten-minute bursts.

The storm hit on Thursday and Friday, and downed trees along many of the roads. But by the weekend local people had been out with power saws to remove the fallen trees.

The weekend also saw neighbors, church groups and everybody else jump into action. Two of our elderly church members had a generator and started feeding their neighborhood. One of their neighbors had cisterns filled with rainwater, so our friends made 5 pots of coffee for their neighbors. One guy was a generator expert, and he offered to accompany me home to try to get a generator started for our next door neighbor and best friend here. People were out in the streets, helping wherever they could. It was inspiring to see.

Access to water was also a huge priority in the aftermath of the storm.

Initially, we used a drainage ditch to fill plastic jugs with water for toilet tanks. When the ditch ran dry, a neighbor escorted me to a springfed pool in our community. The water is beautiful, and he gave me some cheesecloth to use for straining, saying it could be boiled and would be suitable for drinking... Ingle’s [a regional supermarket chain] set up a drive-through system and refilled a gallon jug per person early in the week, just to get people by. Ingle’s and FEMA volunteers also handed out food, toilet paper, baby diapers, and all sorts of supplies, again free of charge. Cars snaked through the parking lots, and dozens of volunteers assessed needs and then gathered the items.

Local churches also stepped in:

First Presbyterian starting providing hot lunches to hundreds of people. Mail service resumed on Tuesday, much to our amazement.

Finally, the power failure meant that fridges had to be emptied, but there was no operating refuse service. Rubbish can’t be left outside because of the bears. Again, people helped out: a neighbour stopped by to say that her sister had arrived with a pickup and would haul their rubbish into Georgia, where refuse facilities were working fine.

Power was restored by Tuesday in Black Mountain, where he lives, and phone and internet by Thursday, a week after the hurricane hit.

One of the things that all of this reminds me is that one of the myths about crises is that communities become lawless and fall apart. In fact, as Rebecca Solnit discovered when writing A Paradise Built in Hell, the opposite happens:

In the wake of an earthquake, a bombing, or a major storm, most people are altruistic, urgently engaged in caring for themselves and those around them, strangers and neighbors as well as friends and loved ones. The image of the selfish, panicky, or regressively savage human being in times of disaster has little truth to it. Decades of meticulous sociological research on behavior in disasters, from the bombings of World War II to floods, tornadoes, earthquakes, and storms across the continent and around the world, have demonstrated this.

As I’m writing this, the state of Florida is busy cleaning up after Hurricane Milton, which, like Hurricane Helene, was more intense because of a confluence of conditions caused by climate change.1

Meanwhile, Florida’s lawmakers spent time earlier this year expunging references to “climate” from new state energy laws as they reversed earlier green energy commitments. It’s almost as if Governor de Santis had read the story of Canute and not realised that it was a parable about the limits of human power in the face of the natural world.

(Source: @GovRonDeSantis on X: 15th May 2024.)

2: Understanding the Nakba through a legal lens

I read Philippe Sands' book East West Street earlier this year, which tells the story of the invention of both human rights law and the law on genocide in the middle of the twentieth century. The book is partly biographical.

The development of human rights law was mostly the work of Hersch Lauterpacht; the law on genocide mostly the work of Raphael Lemkin. Curiously, both men were Jews born in Lviv, in eastern Europe (now part of the Ukraine), within three years of each other, and studied under the same professor, who seemed antipathetic to their developing ideas as students but brought the best out of them in his teaching.Sands, of course, is a distinguished human rights lawyer, and wraps the legal history around biographies of both men, and some of his own family history, for his grandfather was also born in Lviv around the same time. The histories of Lauterpacht and Lemkin—which are inevitably associated with the Holocaust—are very similar to Sands' family history.

Sands, of course, is a distinguished human rights lawyer, and wraps the legal history around biographies of both men, and some of his own family history, for his grandfather was also born in Lviv around the same time. The histories of Lauterpacht and Lemkin—which are inevitably associated with the Holocaust—are very similar to Sands' family history.

The important point here, though, is that neither of these branches of law existed before they were developed by these legal scholars. And, onc developed, both needed to be tested in legal settings. This is how new law develops. I don't have the book to hand as I write, but I recall that the case for human rights law was easier to develop--it had greater consonance with existing bodies of law.

Hersh Lauterpacht was also a figure who was more comfortable in the legal establishment. He settled in Cambridge University, and became an eminent member of the British legal establishment. He advised the British judges at the Nuremberg trials, and drafted some of their arguments for them, as well as meeting the American lawyer Robert Jackson--the US Chief Prosecutor at Nuremberg--ahead of the trials to discuss legal strategy.

The legal arguments for a law on genocide were harder to make, and Lemkin was always less well-established than Lauterpacht, and had to work harder to get acceptance for his idea. He was, frankly, a bit of a hustler, turning up univited at Nuremberg, for example, to press his case. Eventually, he got to draft the United Nations Genocide Convention.

(Raphael Lemkin)

This is a long way in to a story in The Intercept from June about an article in Columbia Law Review's May edition that made the case for understanding the Nakba in a legal sense as a series of overlapping legal frameworks. Nakba means “catastrophe in Arabic, and is used in the context of Palestine, according to Wikipedia, to refer to

“the ethnic cleansing of Palestinian Arabs through their violent displacement and dispossession of land, property, and belongings, along with the destruction of their society and the suppression of their culture, identity, political rights, and national aspirations.”

The article had been written by a Palestinian legal scholar, Rabea Eghbariah, and finalised only after months of editing, review, and revision.2 The Columbia Law Review is run by law students (I had not been aware of this before) and when the article was published, the journal's Board responded by shutting the entire website. It remained shut for three days.

Of course, the politics of this are almost as interesting as the legal arguments. It follows a pattern of conflict between students and university administrations, in the US and elsewhere, over the war in Gaza.

The Board's justifications for their actions included claims that the article had not gone through the journal's normal editorial processes—strongly denied by the student editors—among other persiflage.3 The website was reinstated, according to a later Intercept story, after the editors threatened to stop work on future editions of the Columbia Law Review because they thought the Board’s intervention amounted to censorship. Eghbariah’s article can be found online, but the website's usual page link to a pdf of the full article still seems to be missing.

Eghbariah’s response to this standoff: it was an example of “the Palestine exception.”4 But there’s something about Palestine—this was true long before the war in Gaza—that means that mention of it immediately reveals the power relationships within an organisation. The eventual publication of the article meant that he became the first Palestinian scholar to publish in the Columbia Law Review.

I’m not going to be able to do justice to a hundred-page article in the space, and probably don’t have the legal expertise to do this either, but I can try to sketch out some of the lineaments of the argument. At its heart, Eghbaria is trying to identify the different legal structures that sit behind the components of Israel’s oppression of the Palestinian people:

[T]he Nakba has undergone a metamorphosis; it has evolved from a historical calamity into a brutally sophisticated structure of oppression.

Activists have compared this structure to the South African apartheid system over the years, and in the last year arguments that Israel’s attack on Gaza represents a form of genocide have been made by scholars of the law on genocide. Eghbaria suggests that each of these individual comparisons don’t do enough to understand the legalities involved:

[The article] positions displacement as the Nakba’s foundational violence, fragmentation as its structure, and the denial of self-determination as its purpose. Taken together, these elements give substance to a concept in the making that may prove useful in other contexts as well.

The value of identifying Nakba as a legal concept, says Eghbaria, is because it recognises a particular form of violence:

Naming certain manifestations of violence and oppression and assigning them legal meaning lies at the core idea of what law is... Consider, for example, the recognition of sexual harassment or hate crimes as distinctive legal categories that highlight crucial facets of a behavior which is often already prohibited. Underlying this notion is an understanding that violence committed against members of a particular group is regarded as especially heinous and therefore deserving of distinctive recognition in the legal domain.

The final sections of the paper (from p.972 onwards) analyse forms of violence (and beyond Palestine) in ways that will be of interest to those who are more generally involved in peacebuilding. This is the analytical distinction he makes—mentioned above—between the foundation of the violence; the structure that enables the violance to continue; and its purpose (the “beneficiaries”, if you are using Midgley’s soft systems categories).

Eghbaria’s underlying point here, which he makes in the conclusion, is that it is necessary to understand these legal frameworks as a first step before we can even think about how to start work on resolving the endless tragedy of Palestine. But, he says, there are also universalist lessons here as well:

If Apartheid taught us about the dangers of racialism and the possibility of reconciliation, and the Holocaust taught us about the banality of evil and warned “Never Again,” the Nakba can complicate our understanding of these lessons by reminding us that group victimhood is not a fixed category, and that a victimized group may easily become victimizers. That once the abuses of the Nakba are redressed, Palestinians will also have to transcend their own victimhood.

Having looked through the article, it is serious and considered. It locates its arguments within the history of international law. Its history of Palestine is measured and endlessly footnoted. The fact that the Columbia Law Review Board tried to suppress it is clearly about politics rather than scholarship. But in one way the student editors have had the last laugh. Precisely because the Board tried to prevent publication, the article has been much more widely read than it would have been otherwise.

j2t#607

If you are enjoying Just Two Things, please do send it on to a friend or colleague.

The US naming convention seems a little random, unlike the ‘storm names in alphabetical order’ preferred by the British Met Office.

Some of this shows in the article itself: on many pages the explanatory and clarificatory footnotes take up most of the page.

Given this response when a carefully argued, much reviewed article is published, I wouldn't have blamed the editors for revising their processes to enable the article to be published, given the response when it was published.

Indeed, one of the footnotes to the article reveals that he has previously had an article suppressed by the Harvard Law Review.