12 May 2023. Refugees | Eurovision

Breaking the Law of the Sea // The Eurovision Song Contest is politics by other means.

Welcome to Just Two Things, which I try to publish three days a week. Some links may also appear on my blog from time to time. Links to the main articles are in cross-heads as well as the story. A reminder that if you don’t see Just Two Things in your inbox, it might have been routed to your spam filter. Comments are open. And have a good weekend!

1: Breaking the Law of the Sea

The Mediterranean Sea is “the largest cemetery”, said Dr Tugba Basaran in a lunchtime talk at the Fitzwilliam Museum on Wednesday. (I was able to join virtually). 26,811 people have died or are missing at sea in the Mediterranean since 2014.

The talk was mostly about refugees and their rescuers (or not), but it didn’t start there. It started with Aeneas and The Aeneid. The Mediterranean, she reminded us, has always been a dangerous place, and some of its most famous stories are about refugees. Aeneas had to sail the Mediterranean looking for a home after the fall of Troy.

(The Shipwreck of Aeneas, 1602. Multiple artists. National Galleries of Scotland.)

Dr Barasan, who is the Director of Cambridge University’s Centre for the Study of Global Human Movement, didn’t make this connection explicit, but when she put like that it didn’t sound so different from, say, Syrian refugees escaping from the war there.

The second place she started was with the philosopher Peter Singer, and his famous shallow pond problem. This is Singer’s own version of the problem:

On your way to work, you pass a small pond. Children sometimes play in the pond, which is only about knee-deep... As you get closer, you see that it is a very young child, just a toddler, who is flailing about, unable to stay upright or walk out of the pond... If you don’t wade in and pull her out, she seems likely to drown.

Wading in is easy and safe, but you will ruin the new shoes you bought only a few days ago, and get your suit wet and muddy. By the time you hand the child over to someone responsible for her, and change your clothes, you’ll be late for work. What should you do?

Of course, when you try this out on people, they say you should save the child. It’s a shame about the shoes, and you’re sure that your boss will understand when you get to work.

Singer’s philosophical point is that it doesn’t really matter where the child is—that if you can save its life, without danger to yourself, then you should.1

Barasan’s point, though, wasn’t about the cost of shoes as against a child’s life. It was to underline that the same principle is encoded in the 1982 United Nations Law of the Sea. Article 98 imposes an unconditional obligation on all ships at sea of the duty of rescue, as long as can be done without putting your own ship in danger. Here’s the relevant text:

Every State shall require the master of a ship flying its flag, in so far as he can do so without serious danger to the ship, the crew or the passengers:

(a) to render assistance to any person found at sea in danger of being lost;

(b) to proceed with all possible speed to the rescue of persons in distress, if informed of their need of assistance, in so far as such action may reasonably be expected of him.

Despite this legal obligation, she reeled off a series of cases where either this obligation has been ignored, or people had been arrested for complying with it.

In 2011, 72 people left the North African coast, and their vessel got into difficulty. Nine people survived. They were ignored by trawlers and by a large military vessel. A helicopter dropped water and biscuits to them but did no more. The survivors have been trying to get this case taken up by the courts, without success.

In 2004, the Cap Anamur, a vessel run by an NGO that has the goal of helping refugees, picked up some refugees in distress, and landed in Italy. The ship was seized, and the director of the organisation, the captain and the first officer, were detained for aiding illegal immigration. After three years the case was dismissed.

Similarly, in 2019, Sea Watch-3 run by a German NGO, rescued 53 people in international waters, 60 miles off the Libyan coast, and the captain headed for Lampedusa in Italy as the nearest safe port. On entering Lampedusa, the captain was charged with aiding and abetting illegal immigration, failure to comply with the order not to enter Italian territorial waters, and arrested for resisting public officers and a warship. (It was later released).

Finally, in 2007, the crew of two Tunisian boats take 44 people shipwrecked near Lampeusa on board. They are detained on arrival, and their boats impounded. Both captains are found guity and fined and imprisoned, before later being freed by the Court of Appeal.

At this point, it’s worth checking the EU Directive on the Facilitation of Entry, Transit, or Stay, from 2002. This instructs members states “to adopt appropriate sanctions” on

(a) any person who intentionally assists a person who is not a national of a Member State to enter, or transit across, the territory of a Member State in breach of the laws of the State concerned on the entry or transit of aliens.

However, to try to cover itself on The Law of the Sea, it adds that:

Any Member State may decide not to impose sanctions with regard to the behaviour defined in paragraph 1(a) by applying its national law and practice for cases where the aim of the behaviour is to provide humanitarian assistance to the person concerned.

As Dr Barasan said, that shouldn’t read “may”:

This is not optional, this is mandatory.

So what’s going on here? Under the cover of laws about people smuggling, rescue has been criminalised, along with other forms of aid, such as providing food or shelter.

Barasan argued that states are using legal process as a form of punishment, even when they know from the outset that the people charged (as in the case of Cap Anamur or Sea Watch-3) that the boat is not smuggling people.

There are endless costs imposed by criminal proceedings. They can drag on for several years; they take time, they involve being detained, they carry financial costs, there are psychological costs. They also have to prove that they were not people smuggling.

Even in the absence of a guilty verdict, persecution is a sanction.

As she observed all of this undermines the legal duty to rescue—and thus the rule of law—as well as the normal moral duties that we have to strangers.

There’s a clear patina of racism, and not just among those who lose their lives. The Tunisian fishermen clearly got off worse than, say, Sea Watch-3, which has the resources and the lawyers to fight the Italian state, and even expects to have to do this.

She didn’t have time to expand on this point, but Dr. Barasan also observed that this comes down to the way that states have chosen to construct themselves and their moral worlds—to the point where they would rather break international law than rescue people who are dying. They are willing to undermine their own legitimacy as states, which are essentially legal entities, because their fear of the other is so strong. That’s what I take away from the language in the EU Directive.

And closer to home, it’s perhaps worth remembering this the next time a British Government minister threatens to criminalise the Royal National Lifeboat Institution for saving the lives of migrants in the English Channel.

2: The Eurovision Song Contest: politics by other means

It is the Eurovision Song Contest this weekend, being held in Liverpool as a surrogate for Kyiv after Ukraine won last year’s competition but for obvious reasons wasn’t able to host this year’s. And the last thing I expected to see in the Bulletin of Atomic Scientists—the organisation that also maintains the Doomsday Clock—was a long article about Eurovision as a form of soft power.

I’m not going to do a long piece but it’s certainly worth picking out a few highlights.

Some history: The Eurovision Song Contest was invented in 1956, by the European Broadcast Union (EBU) as television started to take off in Europe. The EBU is an organisation that exists to support public service broadcasters, which has evolved as Europe has evolved. Since then it has also become less geographically specific—hence the appearance of some fairly non-European competitors in Eurovision:

Over time, the contest has broadened its reach and also come to be associated with the larger efforts of European unification and solidarity, becoming a venue for pan-European artistic expression and evolving alongside the shifting borders of postwar Europe—despite membership from many non-European and non-EU nations.

Politics. Because the relationship between public service broadcasters and their states is never clearcut, Eurovision tends to have politics spilling out at the edges. Ben Wellings and Julie Kalman of Monash University say in an essay about Eurovision:

Eurovision matters in contemporary Europe because culture (legitimizes) political structures.

The article’s author, Erik English, has a whole lot of examples of how this works in practice. Here’s a couple of those:

Armenia withdrew from the 2012 contest hosted by Azerbaijanand in 2015 used its entry, “ Face the Shadow ,” to mark the centennial of the Armenian genocide at the end of the Ottoman Empire: “Don’t deny / Ever don’t deny/ Listen don’t deny.” Most of Europe recognizes the genocide, with the notable exceptions of Turkey and Azerbaijan.

In 2016, Ukraine’s entry “ 1944 ” was ostensibly about Stalin’s deportation of Tatars to Central Asia, and paralleled Vladimir Putin’s annexation of Crimea. “When strangers are coming … They come to your house / They kill you all and say / We’re not guilty, not guilty.”

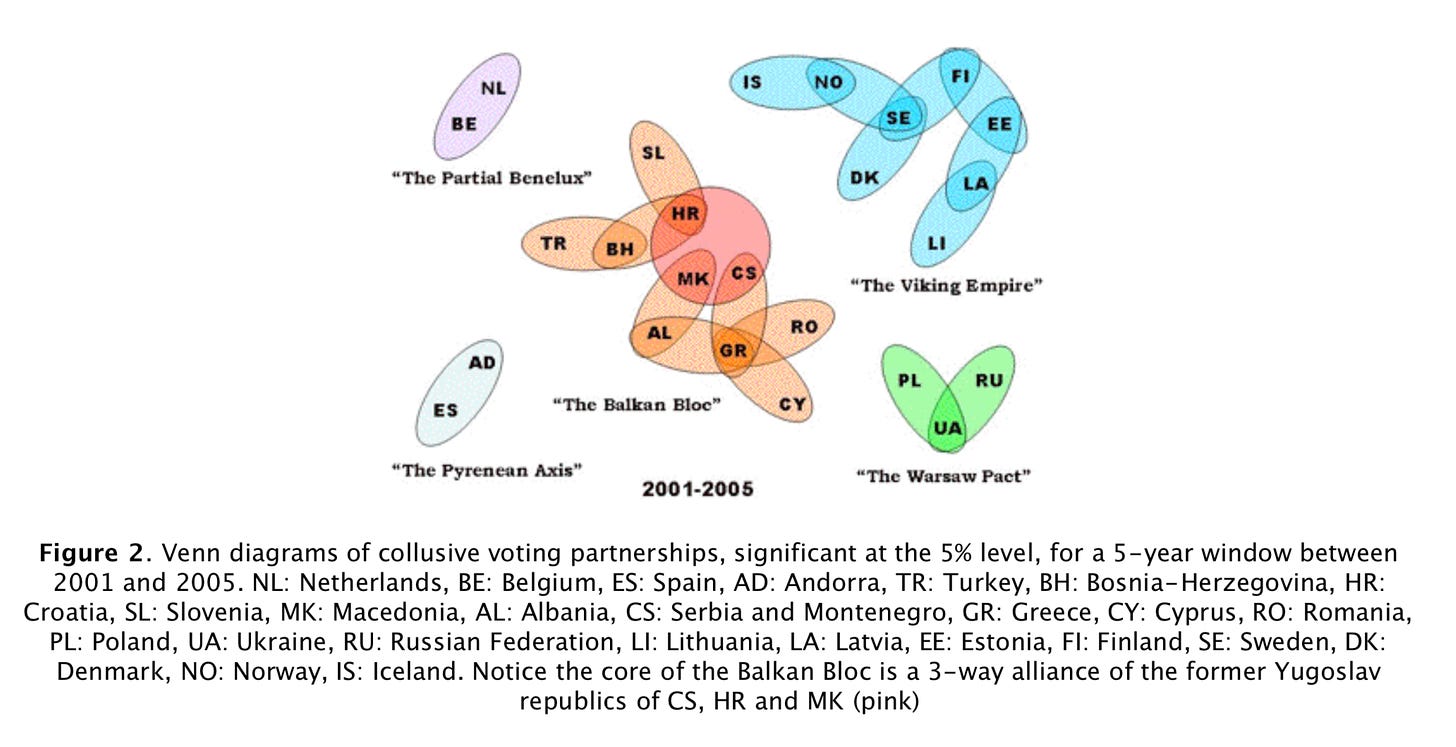

Regional alliances. In the semi-finals, the votes are just cast by viewers (countries can’t vote for themselves). In the final, the vote is split between viewers and national juries. It’s well known that some groups of countries tend to vote for each other, and there’s research on this. Derek Gatherer, who’s a geneticist at Lancaster University, studied voting patterns between 2001 and 2005 and concluded that there were five voting ‘blocs’:

The Viking Empire, the Balkan Bloc, the Warsaw Pact, the Partial Benelux, and the Pyrenean Axis.

These blocs have apparently changed and evolved over time. His article is outside of the paywall, so I went to have a look, partly because I have met Derek a few times and I was curious, and it contains this striking graphic visualising these patterns:

And without falling completely into this rabbit hole, these blocs had become stronger, not weaker, since viewer voting was introduced. Gatherer suggested that these collusive patterns are “a meme”, in Dawkins’ original use of the term:

a horizontally spreading cultural behaviour that has progressively colonised the contest.

Countries can get punished as well. The television presenter Terry Wogan thought that Britain got nil points in 2003 because of its role in the Iraq War, and of course, it got nilled again in 2021, post-Brexit. The songs may just have been rubbish, of course.

LGBTQ+. The show has also seen some interestingly contested gay politics play out, notably since 2013, when Russia passed its so-called “gay propaganda” law, and the following year, when Russia invaded Crimea:

It was in that context that in (2014’s) Eurovision, Conchita Wurst, a gay man and bearded drag queen, won the contest for Austria. Interestingly, jury votes from eastern European countries voiced their disapproval by giving Austria low points, but televoters in those countries awarded Austria high marks—a notable departure from the jury’s establishment perspective. In this way, close study of Eurovision’s public voting patterns can provide insights into changing public attitudes across Europe. Eurovision has a history of supporting the LGBTQ+ community. In fact, the first transgender winner of Eurovision was Dana International , representing Israel in 1998.

And some of this playing out again in this year’s competition. The Croatian entry, Mama ŠČ, attacks Vladimir Putin and Alexander Lukashenko in Belarus in a video that contrasts military imagery with members of the band as dictators wearing drag and playing with nuclear weapons. Spot the symbolism.

j2t#454

If you are enjoying Just Two Things, please do send it on to a friend or colleague.

Not everyone agrees with this, however, and the effective altruists sometimes get into arguments about how expensive the shoes are, although I can’t find the link at the moment.