Welcome to Just Two Things, which I try to publish daily, five days a week. Some links may also appear on my blog from time to time. Links to the main articles are in cross-heads as well as the story.

#1: Reinventing engineering

Peter Curry writes: Human beings are generally quite bad at solving problems in a way that doesn’t involve just adding money and complexity to them. This is a known neurological concept—give people a grid of squares with a pattern, and ask them to make it symmetrical, and they’re more likely to add squares than to take them away.

But this type of engineering is relatively one-dimensional. Firing more money and people at problems can (often!) be helpful, but is also likely not to change the underlying system dynamics. You can end up with ever-more complicated problems with myriad side-effects, and end up missing a cost- and time-effective solution which requires some lateral thinking.

Tega Brain (or Mega Brain, as her fan club calls her) is an artist and engineer. She worked on water drainage and engineering problems before realising that engineering as a discipline had a paradigmatic problem—the technical fix in isolation.

I continue to feel quite frustrated with the way that engineering as a discipline tends to frame problems as technical challenges. You’re supposed to scope out the political and social forces that are causing an environmental problem, and just slap a technical fix on the end of it.

Even the work I was doing — that really nice, innovative, environmental work — was facilitating terrible housing developments full of huge McMansions. It seemed like my job was to make these wildly unsustainable projects just a little bit less bad.

One of Brain’s art projects is called Coin-Operated Wetland.

(Image by Alex Davies, from tegabrain.com)

This features a series of washing machines, which pump the water into an ecosystem containing some plant life, which then use the water, before pumping it back to the washing machines.

What if you show people that there is no downstream? What if you’re confronted with the life forms that are directly impacted by your actions?

‘There is no downstream’ deserves to be the title of a book about systemic thinking, or at least the title of an Enya song or a documentary about sewage or something. I just hope someone uses it.

There’s a caveat - the machine was less efficient than an industrial washing machine, and could only be used once per day. But it did the job. The T-shirts came out clean.

That balancing act reminds me of something engineer and professor Deb Chachra wrote in one of her newsletters. She wrote, “Sustainability always looks like underutilization when compared to resource extraction.”

Now this isn’t necessarily up to the standards of the washing police, who, inspired by Donald Trump, want every dishwasher to go back to blasting dishes with the power of the Niagara Falls. But it is up to the standards of not causing massive water shortage issues in the future. Tough call.

Brain’s other big point about water is about leakage. Water distribution systems leak 10-30% of their water, and because they leak so much water, they actually end up recharging underground aquifers. Brain doesn’t source this claim, so I did some digging, and this article makes a similar claim:

Water transmission pipelines periodically lose an average of 20% to 30% of the water transmitted through them, and those numbers can escalate above 50% in old systems, especially ones that have suffered from inefficient maintenance.

Here’s the battle of ‘engineering as technical fix’ versus ‘engineering as political and social tool’, pitched once more.

Of course, there’s also research going on at MIT and all these engineering schools on how to to develop little autonomous robots that go into the pipes and find the leaks and plug them up. From the perspective of design and engineering, the system is not supposed to be porous; leaks are a problem, an inefficiency.

But it actually takes more than just humans to make the city. What about the street trees and groundwater aquifers that depend on those leaks? So then the question becomes: is there a way we can share resources with other species rather than completely monopolising them?

Tega is a really interesting artist, and I may revisit her work in the future, particularly the stuff about leaks. If you’re interested now, she pioneered ‘smell dating’ and she and Surya Mattu created a project called “Unfit Bits” in order to game the gamification of health insurance.

#2: Stopping coal

Burning coal is still the largest single source of CO2, and China is the world’s biggest user of coal. According to China Dialogue, coal accounts for three-fifths of China’s current electricity consumption, and the country operates half of the world’s coal-fired power plants.

It continues to commission new coal-fired power stations—and these account for half of the coal-fired power plants that are planned or under development worldwide. China also exports coal-fired power plants across Asia.

At this point in the discussion there’s usually a collective shrug, because it’s generally thought that it’s not possible to influence China’s internal energy policy.

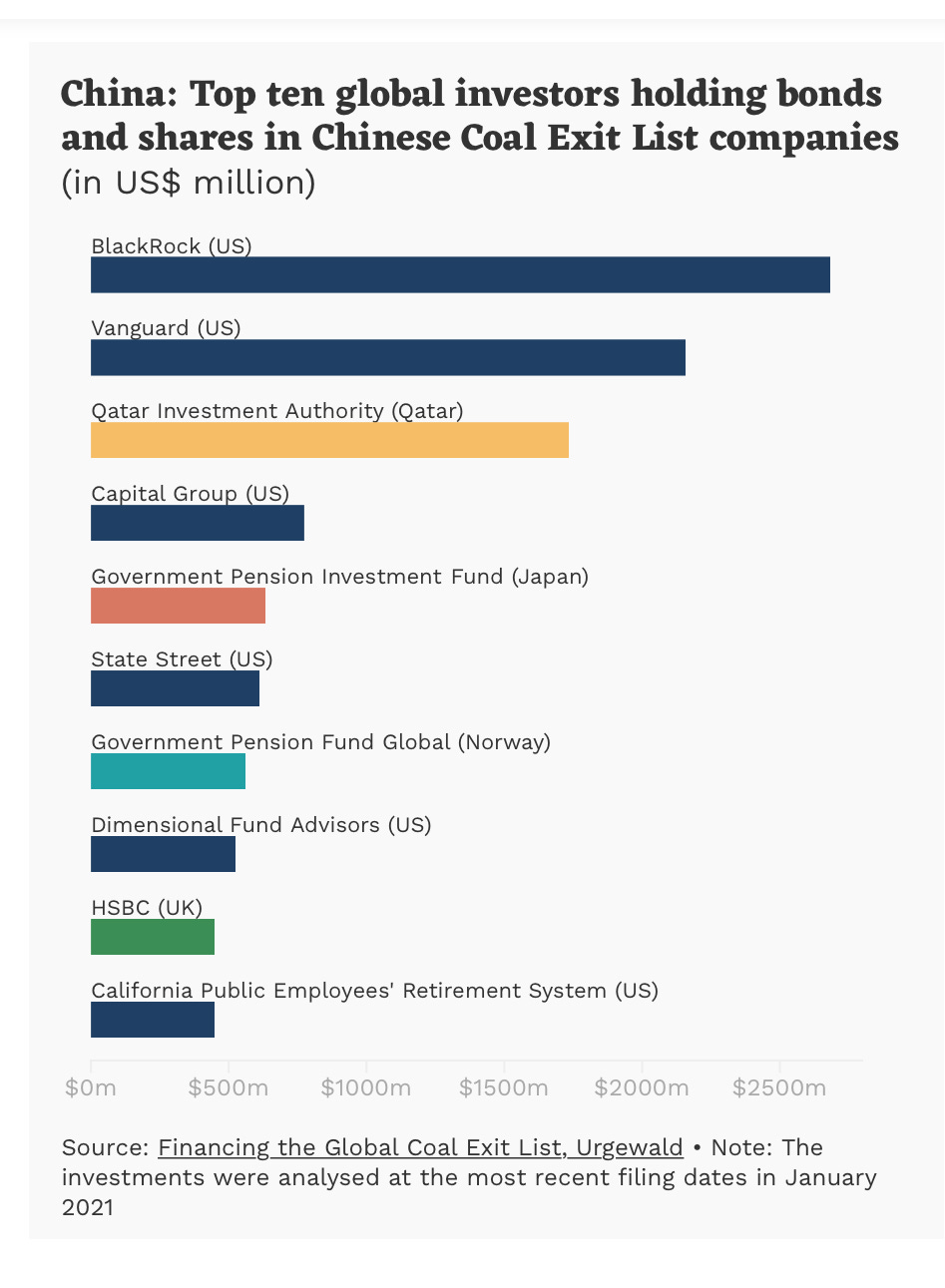

Not so fast, though. The Global Coal Exit List, run by a German environmental non-profit, tracks the investment that goes into financing the worldwide coal industry. It turns out that—over the last two years—10% of the financing of China’s coal plants comes from international banks and investors, with American and British companies right at the head of the queue:

English banks such as HSBC and Standard Chartered have lent $5 billion and US banks such as JPMorgan Chase and Citigroup follow closely behind with $4.9 billion.

Banks from Japan, Switzerland and France have also sunk over $2 billion each into the Chinese coal sector.

Global investors also have big stakes in China’s leading energy companies, through share ownership and bonds. In fact, foreign investment in the Chinese companies on the Global Coal Exit list exceeds Chinese investment.

And right at the top of this list is Blackrock, the very same Blackrock whose Chief Executive keeps writing circular letters about the importance of sustainable investment. There’s also whole slew of European pension funds, and the Japanese Government Pension funds, whose pensioners might be worried about these investments becoming stranded assets.

As might quite a lot of the G7’s central bankers.

j2t#114

If you are enjoying Just Two Things, please do send it on to a friend or colleague.