9th February 2021 | Bezos | Extinction

The unbearable weight of Jeff Bezos; Singing the natural world

Welcome to Just Two Things, which I try to publish daily, five days a week. Some links may also appear on my blog from time to time. Links to the main articles are in cross-heads as well as the story.

#1: The unbearable weight of Jeff Bezos (longish)

The news last week that Amazon CEO Jeff Bezos planned to step away from his role —albeit to the new post of Executive Chairman—after announcing fourth quarter sales of $125 billion, prompted a long article by the tech blogger Ben Thompson that sat somewhere between panegyric and eulogy, with occasional flashes of hagiography:

He is arguably the greatest CEO in tech history, in large part because he created three massive businesses, all of which generate enormous consumer surplus and enjoy impregnable moats: Amazon.com, AWS, and the Amazon platform… These three businesses are the result of Bezos’ rare combination of strategic thinking, boldness, and drive.

Although the FAANG stocks tend to get lumped together, Amazon, Apple and Netflix are different from Facebook and Google: they have actual customers, rather than packaging up their users and selling them on. This was initially a problem for Amazon (compared to say, Google, which started around the same time):

Amazon had to actually pay for the products it sold! To effectively pursue a tech economics strategy, i.e. bet everything on volume in an attempt to gain leverage on huge fixed costs, was exceptionally risky in an arena with inescapable marginal costs.

One of Bezos’ strengths is that he is curious. Early on he noticed Jim Collins’ concept of the ‘flywheel,’ and got him to spend a few days working with his fledgling executive team. I like the idea of the flywheel—a virtuous circle in which each element of the strategy strengthens the whole. I’ve sometimes used it with clients to summarise the implications from futures projects. Thompson murders the Amazon flywheel in his article. Jim Collins’ version (which I’ve redrawn) looks like this:

Obviously this speaks both to Amazon’s obsessive consumer focus, but also to some of the conflicts of interest that sits in the business model. And, of course, the most lucrative part of Amazon, the software platform AWS, isn’t really part of this circle—it was created to underpin all of this, although not everyone would have had the insight to open it up to customers, which built scale and reduced costs. And costs are still, I think, potentially an Achilles Heel for the business.

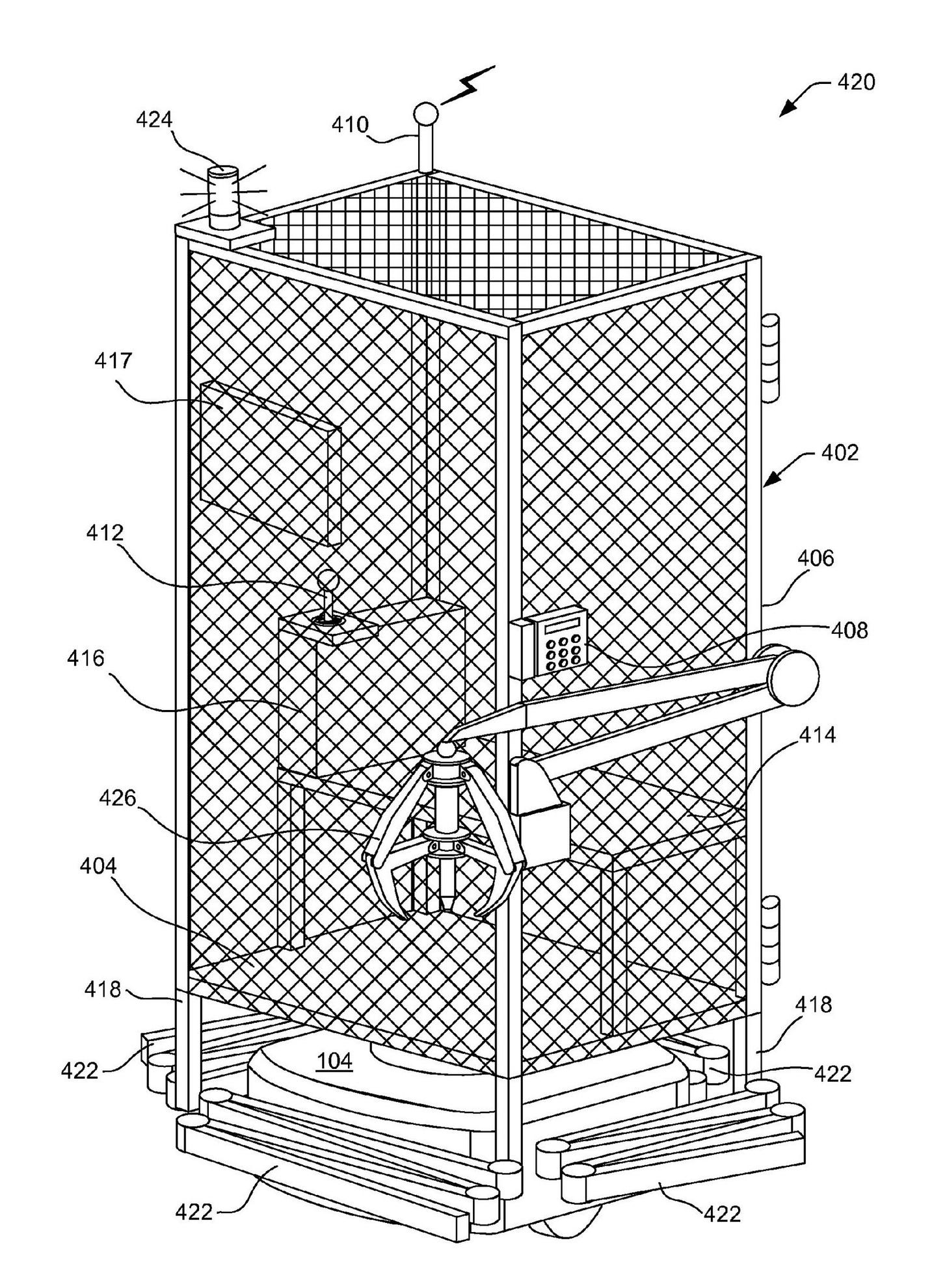

In an unmissable article on Bezos in the Guardian, the writer Mark O’Connell spent more time than was good for him delving into the Bezos story. For him the Amazon patent for ‘The Cage’, never implemented, but referenced in an art and research project that explored the extractive processes that sit behind the Amazon Echo, goes to the heart of Amazon. Yes: this patent would have put workers inside this, apparently for safer stock-picking purposes.

The cage suggests a way of thinking about what distinguishes Amazon as a business, and Bezos as an innovator: the use of technology to push harder and farther than any previous company toward removing, at both ends of the supply chain, the human limitations to capital’s efficiency.

Sometimes when CEOs step away, it is just because they want to spend more time with their money. But sometimes it is because they know that the business is never going to hit the same heights again. (Think Bill Gates at Microsoft or Terry Leahy at Tesco).

So it is worth asking: what grit is out there that might clog up Amazon’s wheel?

Well, there are a few things.

Ben Evans mentions a couple of them in his long presentation “The Great Unbundling”. The first is that big customers abandon the Amazon Market and do their own thing, as Nike has done. The second is that we’re moving into an era of tech industry regulation, in both Europe and the US.

Amazon has a clear history of predatory pricing, as Jacobin noted last week in its account of how the company forced Diapers.Com to agree to being acquired. The current EU case against Amazon is in a similar space: that Amazon uses the information it gains from its Amazon Market platform to compete against third-party sellers as a retailer. The House of Representatives’ tech report comes to a similar conclusion. In most markets where this happens, this is a clear conflict of interest—it’s not inconceivable that the EU will force the company to choose between them if it wants to do business legally in the EU.

Corporate tax is likely to push its way up the public agenda as governments wrestle with lockdown debts. Amazon’s tax behaviour, according to Fair Tax Mark, is even worse than the other Big Tech companies.

Then there is the issue of the corporate culture, which is toxic even for those in the head office, but far worse for those in the warehouses. The National Law Employment Project noted in 2020 that “Amazon has topped the National Center for Occupational Safety and Health’s (NCOSH) “Dirty Dozen” list of employers who put workers and communities at risk for two years straight”. The company did raise minimum wages in the US and the UK, likely for self-interested reasons, but 4,000 Amazon workers across nine states in the US are on food stamps.

The company is well-known for its anti-union activities, perhaps because as one former executive has said, unionisation was “likely the single biggest threat to the business model.” The company’s done everything it can to prevent or delay an impending vote on unionisation in an Alabama warehouse. But then again: companies that care about employment standards don’t feel the need to retain the notorious agency Pinkerton’s to counter workers who are trying to organise. That kind of thing comes from the top.

Amazon seems to push down local wages when it opens new warehouses or distribution centres in your area, which may become more significant as local politicos become more sophisticated in thinking how best to build local economies.

One of the quotes that Bezos is famous for is the things that aren’t going to change. He’s said versions of this on multiple occasions:

Bezos said people often ask him to predict what will change over the next decade, but asking what won't change over 10 years can offer potentially more valuable insight… For Amazon, the obvious answer is that customers will always want low prices, fast shipping and a large selection.

Amazon is dependent on a huge logistics infrastructure, and one racing certainty is that the carbon cost of this is going to increase over the next decade, possibly quite quickly. Transport always has a higher emissions cost when it’s faster and more complex, and especially when planes are involved. It’s possible Amazon will end up with trade-offs between speed and price, or two-tier delivery systems.

In other words, there are externalities everywhere. When we look back at Jeff Bezos’ career, we’ll see someone who spotted the internet early, and rode it brilliantly. But we’ll also see an old-fashioned 20th century American tycoon who did whatever he could to make sure that the costs his businesses generated ended up being paid by other people. There are good reasons to think this might be coming to an end. Maybe it’s a perfect moment to kick yourself upstairs.

#2: Singing the natural world

Music to Save Earth’s Songs is a cultural project by Oregon State University which asks writers and musicians to collaborate to mark the songs (actual and metaphorical) of species that are threatened with extinction. Over the coming weeks they are releasing to their youtube channel and elsewhere a range of short pieces that in different ways try to address the speed of species extinction going on around us at the moment.

The series is inspired by the work of the nature writer Kathleen Dean Moore. As the introductory page reminds us,

In the 50 years that Kathleen has been writing about nature, roughly 60 percent of all individual mammals have been erased from the face of the Earth—six of every 10. The total population of North American birds, the red-winged blackbirds and robins, has been cut by a third. Half of grassland birds have been lost. Half of butterflies and moths. We are "laying waste the sky," as Thoreau warned.

There will be a series of live events and 20 short video pieces released over the life of the project. Some are already up, including the premiere of a new piece caslled “Extinction Variations”.

j2t#027

If you are enjoying Just Two Things, please do send it on to a friend or colleague.