Welcome to Just Two Things, which I try to publish daily, five days a week. Some links may also appear on my blog from time to time. Links to the main articles are in cross-heads as well as the story.

One of the big questions—as the vaccines roll out—is the extent to which people in white-collar service and knowledge economy jobs will go back to working in the office again.

On the one hand, it seems unlikely that they’ll still be commuting to offices four or five days a week. Nobody likes commuting, after all. On the other hand, received wisdom says that the current knowledge-driven configuration of the city depends on proximity.

(Image: Dror Poleg)

And some of our more sociopathic businesses—Amazon, Goldman Sachs—have already said that they want their employees back at their desks after the pandemic.

In a recent edition of his newsletter, Dror Poleg has tried to evaluate how these two conflicting ideas are likely to play out: the sense that workers will be entirely happy going to the office a lot less, versus the imputed knowledge value of office proximity:

Over the past two decades, the working assumption was that large urban centers are more productive because:

They enable "knowledge spillovers" and spontaneous interactions between people, which, in turn, lead to new ideas… and

They have deep labor pools that facilitate better matching of candidates to jobs…

These two factors multiply one another. In-person interaction between well-matched employees produces better and faster economic growth. The post-Covid world puts these factors on a collision course.

In the piece, Poleg uses Amazzon as a small thought experiment. Once it had announced that it would return to "office-centric culture", some employees threatened to leave. Amazon engineers are well paid, so the company is probably confident that it could replace them. But, by insisting they show up every day, it is limiting its talent pool. In addition, this pool may have shrunk as a result of people moving away from expensive cities during the pandemic. So: “Amazon is doubling down on in-person interaction at the expense of access to a smaller talent pool.”

Twitter, in contrast, is making the opposite bet, and doubling-down on remote work—and access to a larger talent pool. Which one will win? Well, we don’t know yet. But Poleg works through the equation:

[The level of in-person interaction] multiplied by [the size of the talent pool] equals [The rate of innovation and financial success]. Amazon chose to maintain the level of in-person interaction and reduce the size of the talent pool. Twitter chose to dramatically reduce the level of in-person interaction and dramatically increase the size of the talent pool from which it hires…. But, all things being equal, I would bet on the size of the talent pool being much more important.

One of the reasons for believing this is that remote working technology has been getting better, and our knowledge about how to use it has accelerated during lockdown. So physical proximity may be becoming less important in terms of ensuring good interaction. There are also more examples of successful virtual organisations out there to learn from. (SOIF, where I work, is one of these: I have many good colleagues that I have never met in person).

A second reason is that, at the top end of the labor market, talent has a lot of power. Once some talent decides it wants to work in certain ways, more talent tends to follow. The growth in Europe of four-days-a-week working is a case in point.

My own instinct is that we will look back at the dense “knowledge city“, as per Edward Glaeser and others, as the last throw of an old urban model. It has too many externalities locked in to it to be sustainable, in terms of its environmental footprint and its costs of social reproduction.

But if you want the other view, the geographer Enrico Moretti is very happy to explain the logic, as he did recently in Vox.

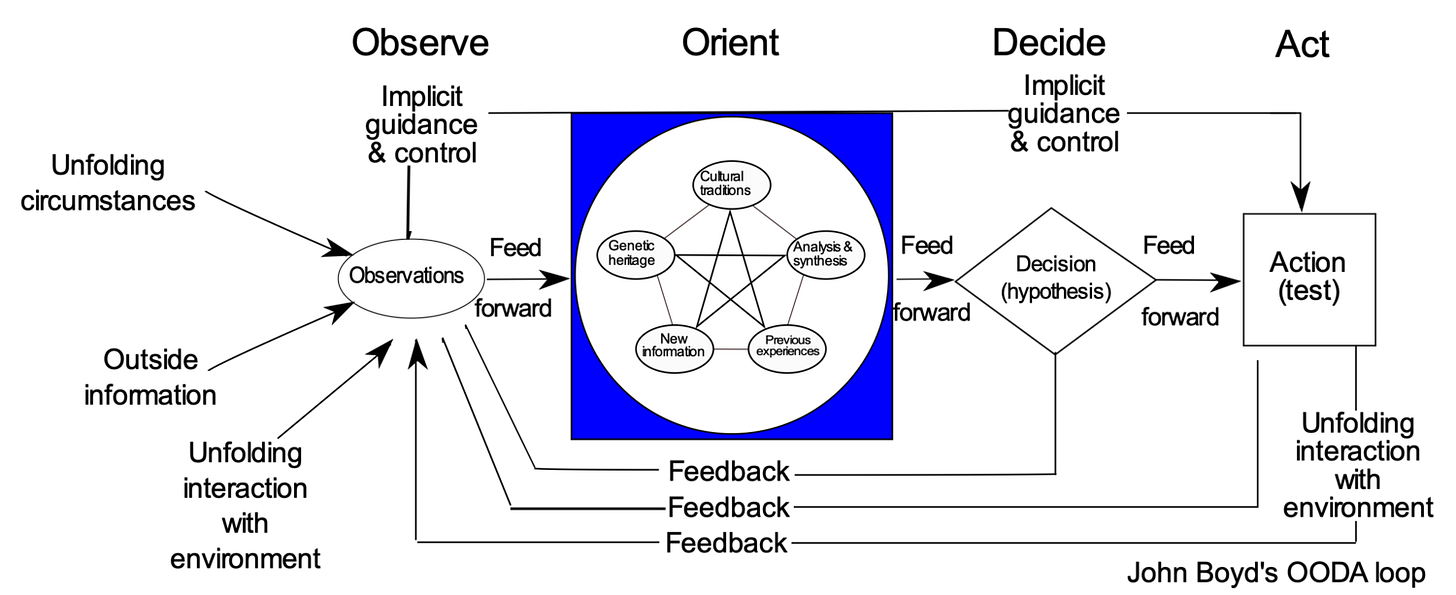

Readers probably know that OODA—an acronym for Observe-Orient-Decide-Act—is a military decision model. It was developed by an American Air Force Colonel, John Boyd, who added the second ‘O’, for ‘Orient’ to an existing military decision model.

His story, and the story of his decision model, was told in an edition of the BBC’s Sideways podcast, presented by Matthew Syed. (28 minutes)

Boyd was a combative man who was a bit of a loner (only one member of the USAF turned out for his funeral). But by all accounts, the addition of ‘Orient’ to the decision cycle was a revolutionary insight in terms of military strategy.

(Source: Patrick Edwin Moran, CC BY 3.0, via Wikipedia)

The OODA loop caught the eye of the then Defense Secretary, Dick Cheney, just before the first Gulf War. The podcast suggested that it was influential in shaping American tactics. True to character, Boyd didn’t write a book about his ideas, and the only way to learn it was on an intensive military course, with hundreds of ‘foils’.

But after his death, word did get out. One reader was Dominic Cummings, who ran the Brexit Leave Campaign using OODA as a template, and seems to have taken it into Downing Street when he became Prime Minister Johnson’s lead adviser.

However, there’s an important difference between military and political campaigns on the one hand, and governing on the other. The former are zero-sum games; the latter is not.

Cummings no longer works in government, but it’s hard not to think, watching British government stunts like the recent report on race, or the endless misrepresentations as to the status of the Brexit agreements, that the British government is still working from an OODA template. It still thinks that government is a zero-sum game which others have to lose if it is to win.

j2t#073

If you are enjoying Just Two Things, please do send it on to a friend or colleague.