9 May 2023. Millionaires | Knowledge

Millionaires are just terrible for the the climate. // Helping knowledge to move around

Welcome to Just Two Things, which I try to publish three days a week. Some links may also appear on my blog from time to time. Links to the main articles are in cross-heads as well as the story. A reminder that if you don’t see Just Two Things in your inbox, it might have been routed to your spam filter. Comments are open.

1: Millionaires are a huge climate policy problem

As the Canadian writer and activist Cory Doctorow insists, every billionaire is both a policy mistake and also a policy problem. And we know already that billionaires are bad for climate change.

But research from Stefan Gössling and Andreas Humpe, published initially at the end of last year in Cleaner Production Letter (open access) suggests that when it comes to climate change, millionairesare just as much of a problem. They don’t have so much money, of course, but there are a lot more of them, and our largely laisser-faire economic policies mean that more are being created all the time.

And Gossling and Humpe’s research suggests that we can try to limit emissions to a level compatible with 1.5 degree warming, or we can have economic policies that tolerate the generation of more millionaires at present rates of growth, but we can’t have both. From the abstract:

(W)e present a model that extrapolates observed growth in millionaire numbers (1990–2020) and associated changes in emissions to 2050. Our findings suggest that the share of US$(2020)-millionaires in the world population will grow from 0.7% today to 3.3% in 2050, and cause accumulated emissions of 286 Gt CO2. This is equivalent to 72% of the remaining carbon budget.

The implications of this are spelled out:

Continued growth in emissions at the top makes a low-carbon transition less likely, as the acceleration of energy consumption by the wealthiest is likely beyond the system's capacity to decarbonize.

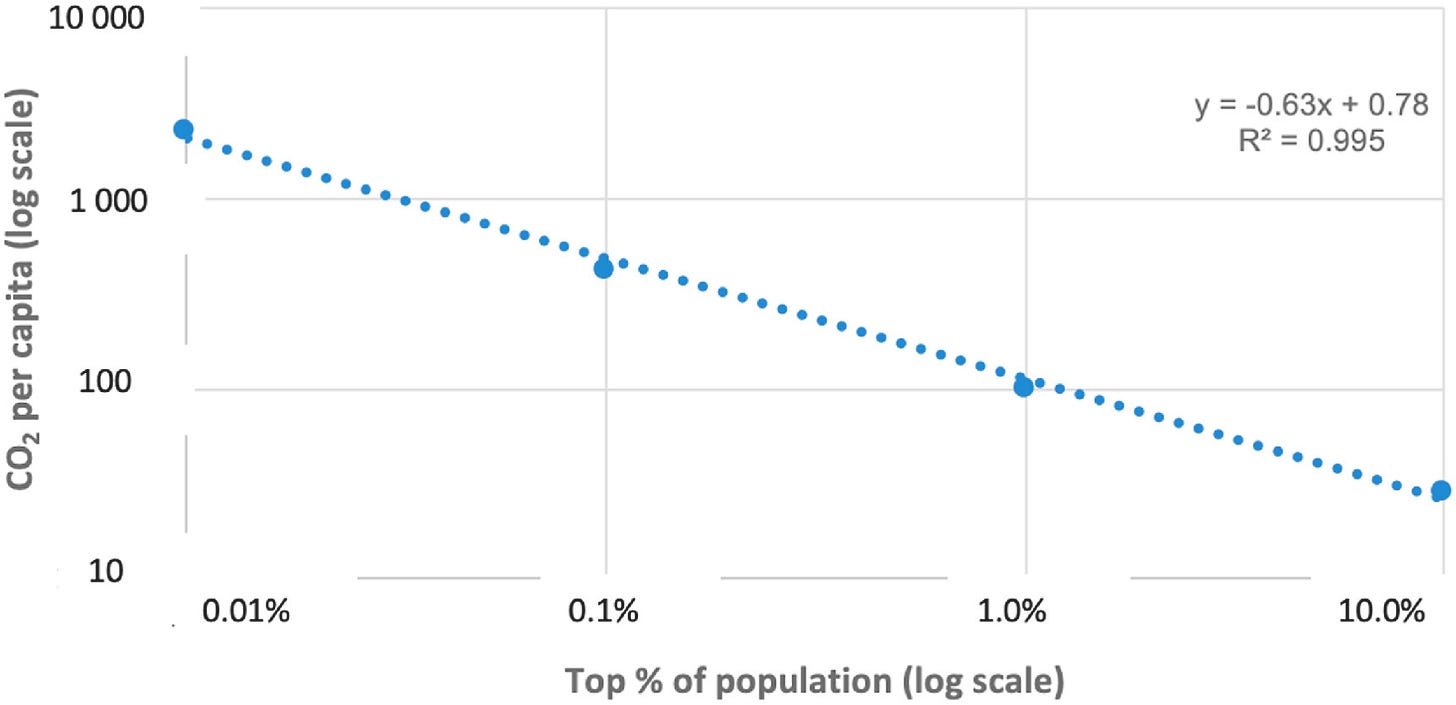

It’s well known that wealthier people contribute a greater share of emissions than poorer people do, and even among the top 10% of the world’s population the differences between the fairly rich and the extremely rich in terms of emissions are striking.

This relationship turns out to be logarithmic. As people get exponentially richer, so their emissions go up exponentially as well:

(Global emission inequality in 2019. Source: illustration by authors, based on Chancel, 2022a, Chancel, 2022b data.)

The layout here is a bit confusing, by the way, since on the horizontal axis people get richer as the line heads to the left.

The second building block here is about the number of millionaires. The authors use data from 2010 to 2020 from Credit Suisse, which shows a 7.9% growth rate year on year over that time. It’s hard to know if it is possible to extrapolate that figure, which is what they do with it, since some of the other wealth trends were accelerated in that time by the impact of quantitative easing on assets prices worldwide.

But it seems unlikely under current prevailing economic policies that the number is going to shrink, given the reluctance of governments to impose any form of wealth tax, the ineffectiveness of inheritance taxation, the amount of the world’s wealth held offshore, and so on.

The other part of this calculation, of course, is about the carbon-intensity of millionaire spending. None of this would be a problem if there were evidence of a (radical) decoupling of emissions from top end spend. The researchers have a go at assessing this, although their data is more from the billionaire end of the market (yacht emissions and so on) but this shows, if anything, that the carbon intensity of this is increasing rather than decreasing.

Similarly, private jet usage among the wealthy is increasing faster than commercial jet usage (there’s separate information on this elsewhere), and this is far more carbon intensive. 14 times as carbon intensive, in fact. All the same, their model assumes that there are some efficiency gains in millionaire consumption between now and 2050, but that this has a relatively low impact on total millionaire emissions because of the increase in total worldwide millionaire numbers.

Which gets us to the killer chart:

(Remaining carbon budget and millionaire emission growth, 2022–2050, under the 1.5 °C scenario.)

What this chart says is that when you look at the planet’s remaining carbon budget under a 1.5% warming scenario, millionaires will consume 72% of it. By 2037, they will be using up all of the global carbon budget.

If we’re giving up on 1.5 degrees and settling for 2 degrees, millionaires will still take up 25% of the global carbon budget.

What this says for me is that even if their projected millionaire numbers are on the high side (for example, if the relatively rapid increase over the last decade wasn’t typical and starts to decline) this is still a problem.

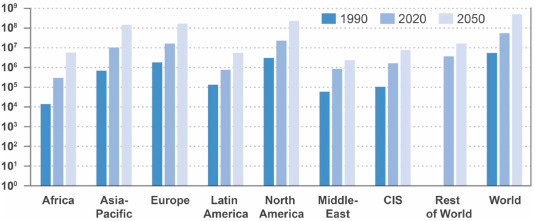

It becomes something of a wicked problem quite quickly after that. Inequality is a greater problem within countries than between them now, and (although they don’t say this) in most countries elites have captured political processes to their advantage. So what this regional chart of millionaire growth rates—actuals 1990 to 2020, extrapolations to 2050–also tells us is that it is going to get harder to take any meaningful action to address this problem:

(Millionaire numbers (nominal) by region: 1990, 2020, 2050. Source: Credit Suisse (2021).)

Their results are also based on direct emissions, and these increase, of course, if embedded emissions are taken into account. So, just to spell out their conclusion:

Our findings suggest that there is a very limited chance of changing emission trajectories to net zero over the next 30 years, if growth in millionaires and their emission patterns continues. Notably, results are based on an assessment of direct energy consumption. Adding embedded emissions, for instance for the construction of superyachts, further emphasizes the importance of climate governance for the wealthy.

They don’t really have a go at what that climate governance might look like if it were translated into policy, instead discussing barriers to policy:

The first barrier is the very realization among policy makers that the wealthy have to be limited in their energy use and guided in their investment decisions. In most countries, wealth accumulation continues to be seen as desirable and beneficial for overall economic growth. The second barrier is represented by increasingly polarized political environments, in which mitigation policies may not be proposed, let alone be implemented.

There’s a third barrier mentioned as well: although the notion that the wealthiest and wealthier contribute disproportionately to climate change is commonplace in media coverage and among NGOs, it hasn’t reached politicians yet. So the policy proposals that do emerge (such as small increases in carbon prices) don’t start to deal with the scale of the issue—or the systemic nature of the relationship between wealth and emissions.

2: Helping knowledge to move around

The Corporate Rebels guys are generating a useful set of resources and information on what it takes to run a modern flat decentralised organisation, even if they can be a bit earnest about it sometimes. I’m also not a fan of their ‘Bucket List’ of organisations they feel they need to visit, if only for the emissions impacts of the travel it seems to involve.

But I was struck by a recent piece they did on ways to share knowledge, which also came with one of their characteristic social/shareable graphics.

(Source: Corporate Rebels)

One recent visit, to foryouandyourcustomers, was typical of the type of company they are interested in. They are a back office digital services company, with 237 employees based in 20 autonomous cells or units; no unit is allowed to grow beyond 25 people:

There is no headquarters, no centralized decision-making, and no overall company strategy.

Of course such a radically decentralised structure can mean that it is hard to share knowledge across the business, and the Corporate Rebels’ trip report focussed specifically on this aspect of the business.

They do this in four ways:

Trust: let good things spread organically

Knowledge moves around by word of mouth. If it doesn’t, it’s probably not good enough, because people aren’t bothering to share it.

CR’s Pim de Morree, who wrote the post, connected this to some related research that says that knowledge moves around better when social ties within a network are weaker rather than stronger:

the research suggests that complex tasks are much easier to tackle when differing teams are only marginally connected. This approach allows for the moderation of information flow, empowering team members to explore unconventional solutions and ideas without being constrained by the limitations of other teams.

Open space: Encourage knowledge sharing through passion

Of course, everyone is passionate about everything these days, aren’t they? (“Passionate about petfood”, etc). Maybe enthusiasm is a better word for this. But foryouandyourcustomers organises an annual multi-day meeting based on Open Space Technology . People are encouraged to share the things they are ‘passionate’ about, and people are free to join the sessions that they are interested in.

Weekly CEO meeting: Share resources and information

The leaders of each of the cells join a weekly call with the CEO where resources are shared. Others can join if they wish. Apparently:

There's no agenda, so the most interesting topics will emerge naturally.

I understand the theory here, which is that people end up talking about the things that are current sources of energy in the business, although I suspect you might need some dialogue rules, and some shared culture, to make sure that you were sharing useful things rather than getting sucked into things that didn’t need everyone’s attention.

Communities of passion: Bring people together around specific interests

The P-word again. I suspect these are what I would call “communities of interest”:

people can voluntarily come together around specific passions or interests, such as design or product development.

But the point is to follow expertise and energy, and do that horizontally across the organisation—and be led by expertise not seniority.

And generally these are driven by these three Es: expertise, energy, and enthusiasm.

j2t#453

If you are enjoying Just Two Things, please do send it on to a friend or colleague.