9 May 2022. Net Zero | Copyright

Voters are concerned about climate change and strongly support Net Zero. Musical difference and a musical commons.

Welcome to Just Two Things, which I try to publish daily, five days a week. Some links may also appear on my blog from time to time. Links to the main articles are in cross-heads as well as the story. Recent editions are archived and searchable on Wordpress.

1: Voters are concerned about climate change and strongly support Net Zero.

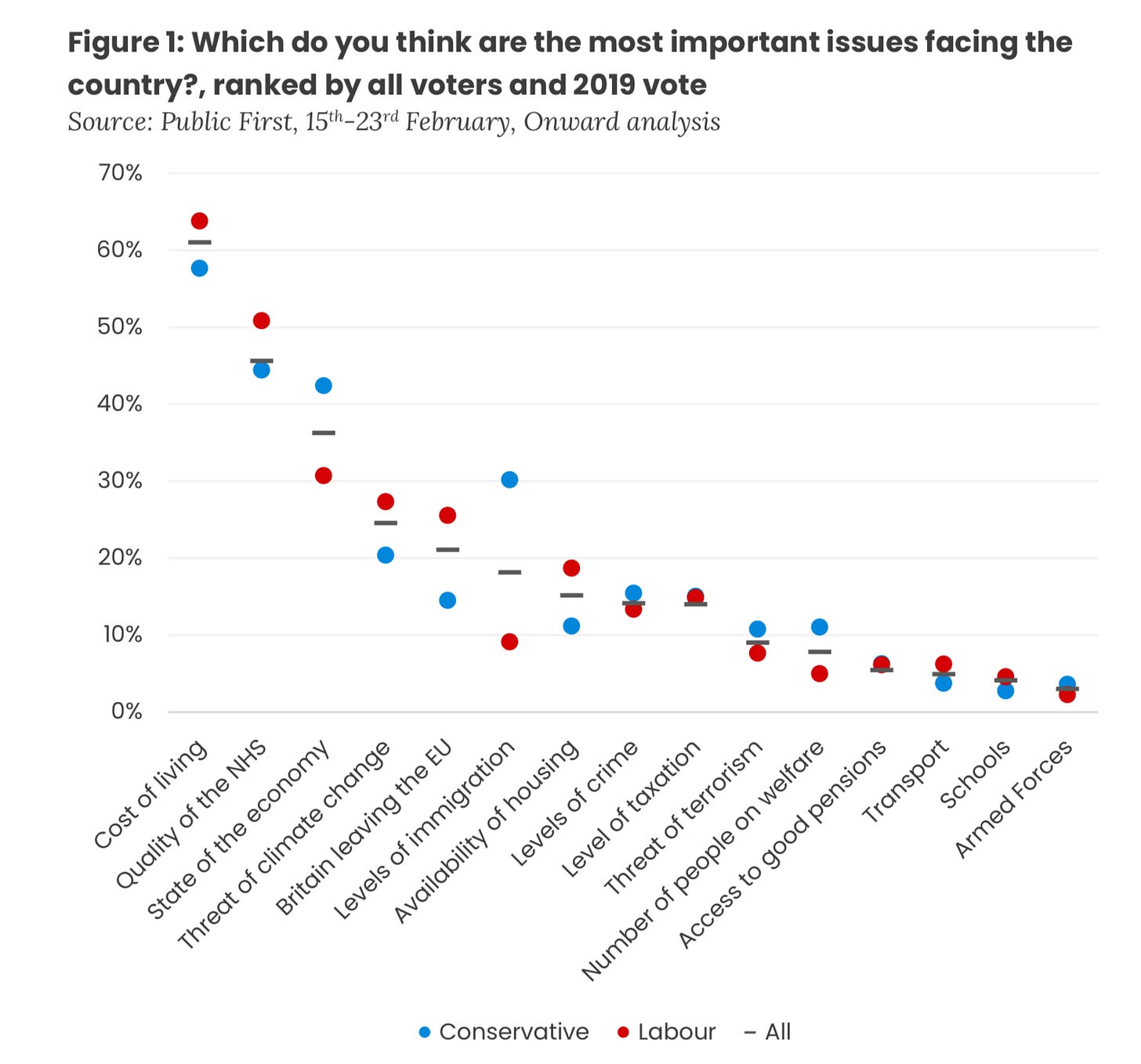

There are a couple of interesting pieces of recent polling research on British attitudes to net zero and climate change, which both suggest that the public is further ahead on climate change than politicians are.

The first is from the right-leaning UK thinktank Onward, and is based on two rounds of opinion polling—the first in the third week of February with a representative sample of more than 4,000, the second in early April (just over 2,000). These are decent samples, especially the first one.

For those who don’t follow British politics, the reason that this is topical is that members of the governing Conservative party have been making noises in the face of a cost-of-living crisis and the war in Ukraine to suggest that they might scrap the Net Zero targets that are currently enshrined in British law.

The conclusion from the Onward report is that this would be politically unwise:

Three fifths (60%) of voters support the UK’s plan to reach Net Zero by 2050. This is six times the share (10%) who say they oppose the policy. And 55% of people agree that “The UK should keep its plan to reach Net Zero by 2050, even if it’s going to be expensive, as we need to stop damaging the environment”, more than double the level (25%) who think the UK should scrap the plan if it is too expensive.

In fact, to spell this out, it seems clear that abandoning Net Zero is a vote-loser:

Nearly half (46%) of voters say they would be less likely to vote for a party that pledged to get rid of the Net Zero target. Only 15% say it would make them more likely to vote for such a party. Ditching Net Zero is unlikely to win back those 2019 Conservatives who say they no longer support the party. Among this group, 51% say they would not vote for a party that got rid of the Net Zero target; only 18% said they would vote for such a party.

And there’s an interesting note on messaging. Focusing on language about the long-term (for example talking about the world we leave for our grandchildren) resonates strongly with both Labour and Conservative votes, both in the high 70s. Language about ‘climate action’ or ‘going green’ means something to younger graduates, but not so much other groups.

Almost all groups rank climate change among the top six issues they are concerned about—even groups for whom climate change is less important. Overall, it is fourth most important, after the cost of living, the state of the NHS, and the state of the economy.

(Source: Onward)

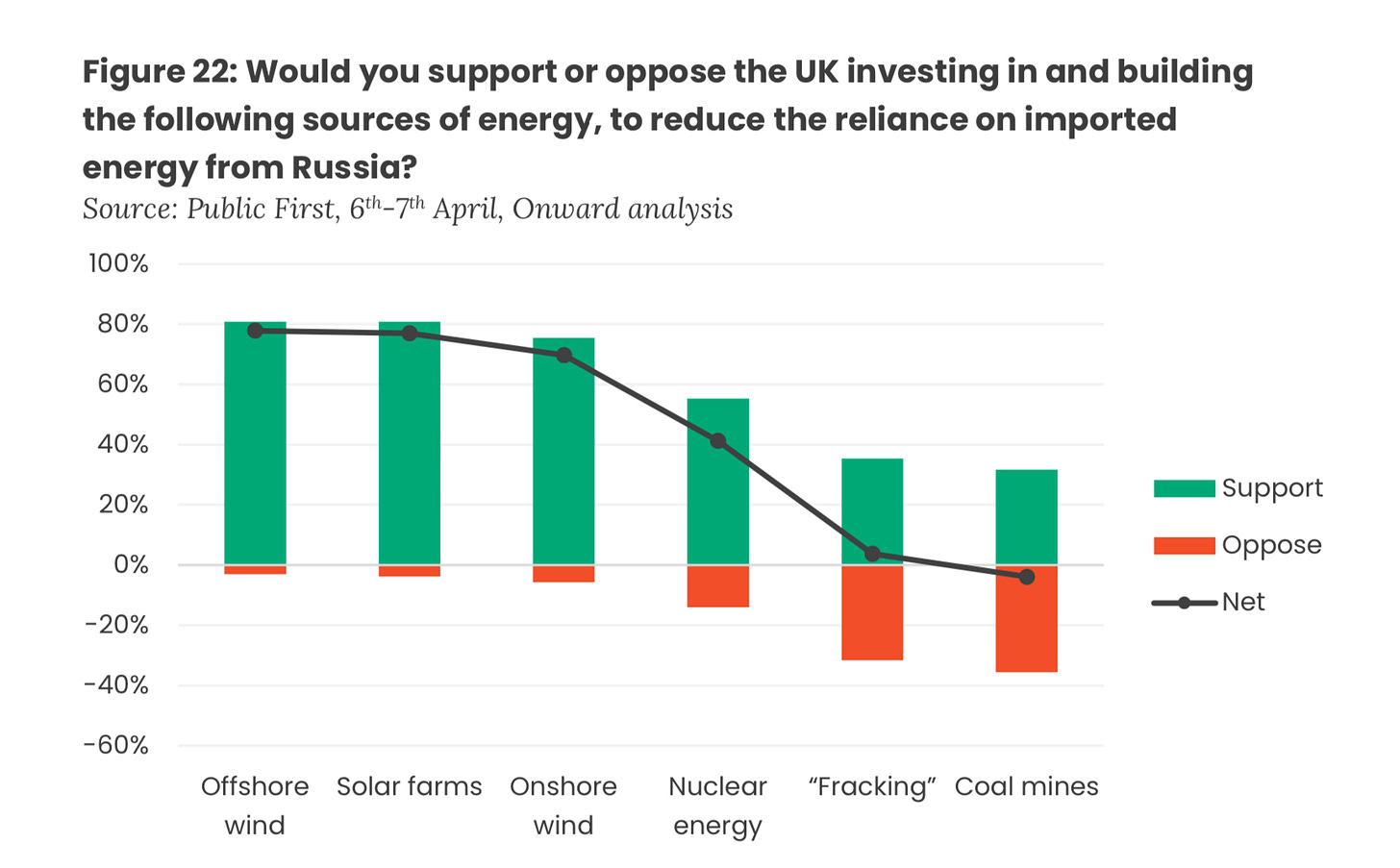

The second poll, in April, was designed to test whether the Ukraine war had influenced attitudes (there’s nothing like a badly timed war to damage a thinktank’s best laid plans.)

The proportion of people who said that the UK should accelerate its plans for Net Zero because of the war was twice as large (55%) as the proportion who said it should slow it down (28%), and when asked about what energy sources we should be investing in to improve UK energy security, renewables are at the top of the list, and by some margin, and fracking and coal at the bottom. Worth noting that the opposition to onward wind—about which there’s endless political noise in the UK—seems pretty trivial here.

(Source: Onward)

On the other piece of polling, a couple of quick paragraphs: The research was done by You Gov for the Social Change Lab, and tracked attitudes to the Just Stop Oil protests over the first three weeks of the protests. The same on each occasion was a nationally representative sample of more than 2,000 adults.

58% of respondents said they supported the aims of Just Stop Oil (23% were against, 19% neutral). (Awareness climbed from close to zero to 63% over the three weeks.) This support might be related to another data point: 26% agreed the government was doing enough on climate change, while 46% disagreed.

It’s also worth noting that while people supported the aims of Just Stop Oil, they didn’t support Just Stop Oil itself (18% support, 57% against). Nonetheless, all of this data seems consistent with the piece I shared here recently on the difficulties in getting juries to convict Extinction Rebellion protesters.

H/t for these links to Jeremy Williams’ Earthbound blog.

2: Musical differences and musical commons

I’m not a fan of British copyright law—the term (70 years after death) is far too long, and the effect of this is to favour music companies and disadvantage innovation and creativity. There’s a reason why early copyright terms ran for 14 to 28 years, depending on where you were.

All the same, as law lecturer Hayleigh Bosher explains in a recent article in The Conversation a recent copyright case involving Ed Sheeran over his song ‘Shape of You’, streamed 3 billion times on Spotify and played 5 billion times on YouTube (and commented on 1.1 million times), has cleared up some of the blurry bits.

(Photo of Ed Sheeran by Harald Krichel, via Wikipedia. CC BY-SA 3.0)

The case was brought by Sam Chokri, who claimed that Sheeran had copied his song ‘Oh Why’.

There have been increasing cases over copyright in recent years (and I couldn’t help wonder if this might have something to do with the way that music has become a ‘winners take all’ market in the online age. Sheeran, for his part, now says he records his songwriting sessions “so that he can prove how he came up with his own song.”

The test for copyright involves two parts. The first part is establishing whether the person accused of copying has heard the other song. Of course, it’s almost impossible to say this for certain in the age of streaming and music everywhere:

Sheeran said that to the best of his knowledge he had never heard Chokri’s song before, but when questioned in court, he couldn’t completely rule out the possibility. “That is why we are here,” he said.

But the second part is about how similar the songs are:

(C)opyright law is not supposed to protect ideas; it only protects original expressions of ideas. Essentially this means that common musical elements are freely available for everyone to use and draw upon, allowing the creative process to flow. But this has to be carefully balanced against giving copyright protection to artists for their original creations so that they can protect, control and be paid for their work.

As is standard for this type of case, both sides called on musicologists to talk about similarities and differences. At the end of the case, the judge decided that the similarities were the ‘commonplace elements’:

Commonplace elements are not – and should not be – protected by copyright, so cannot be infringed.

Bosher’s assessment is that the case improves the balance in copyright law:

Copyright is supposed to encourage artistic endeavour, not stifle it. Thankfully, the outcome of this case puts the balance back where it belongs, only protecting original expressions of creativity.

And you have to like a legal academic who has made a Spotify playlist to illustrate music copyright disputes:

j2t#311

If you are enjoying Just Two Things, please do send it on to a friend or colleague.