9 June 2022. Globalisation | Prostitution

The failure of globalisation. // The simple ugly truths about prostitution.

Welcome to Just Two Things, which I try to publish daily, five days a week. Some links may also appear on my blog from time to time. Links to the main articles are in cross-heads as well as the story. Recent editions are archived and searchable on Wordpress. And a reminder that if you don’t see Just Two Things in your inbox, it might have been routed to your spam filter.

1: The failure of globalisation

I’m on the record as being sceptical about the value of the meetings of the rich and powerful hosted at Davos by the World Economic Forum. Last month it held its first in-person meeting since the pandemic—in May rather than the customary January. So it’s interesting to see an article by the progressive economist Joseph Stiglitz suggesting that the recent meeting represented a deep challenge to the Davos worldview.

The article is behind the Project Syndicate paywall, but in the clear at Social Europe:

(A) forum traditionally committed to championing globalisation was primarily concerned with globalisation’s failures: broken supply chains, food- and energy-price inflation and an intellectual-property (IP) regime that left billions without Covid-19 vaccines just so that a few drug companies could earn billions in extra profits.

The policy talk about this is about ‘friend-shoring’—sourcing supply chains from political allies—and even industrial strategies designed to rebuild domestic capacity. This is a long way away from just-in-time deliveries from the most competitive provider, regardless of location. The result, as Stiglitz says, was ‘cognitive dissonance”:

Unable to reconcile friend-shoring with the principle of free and non-discriminatory trade, most of the business and political leaders at Davos resorted to platitudes. There was little soul-searching about how and why things had gone so wrong or about the flawed, hyper-optimistic reasoning that prevailed during globalisation’s heyday.

But as he points out, globalisation—or more exactly, the economic forms that globalisation took—was a symptom, not a cause. The cause was a lack of resilience:

Just-in-time inventory systems were marvellous innovations as long as the economy faced only minor perturbations, but they were a disaster in the face of Covid-19 shutdowns, creating supply-shortage cascades (such as when a dearth of microchips led to a dearth of new cars).

It’s also a reminder that markets are terrible at pricing risk.

But some of the issues about our lack of resilience aren’t to do with risk, but about monopoly; growing market concentration has gone hand in hand with globalisation ever since Reagan and Thatcher started their deregulation spree in the 1980s:

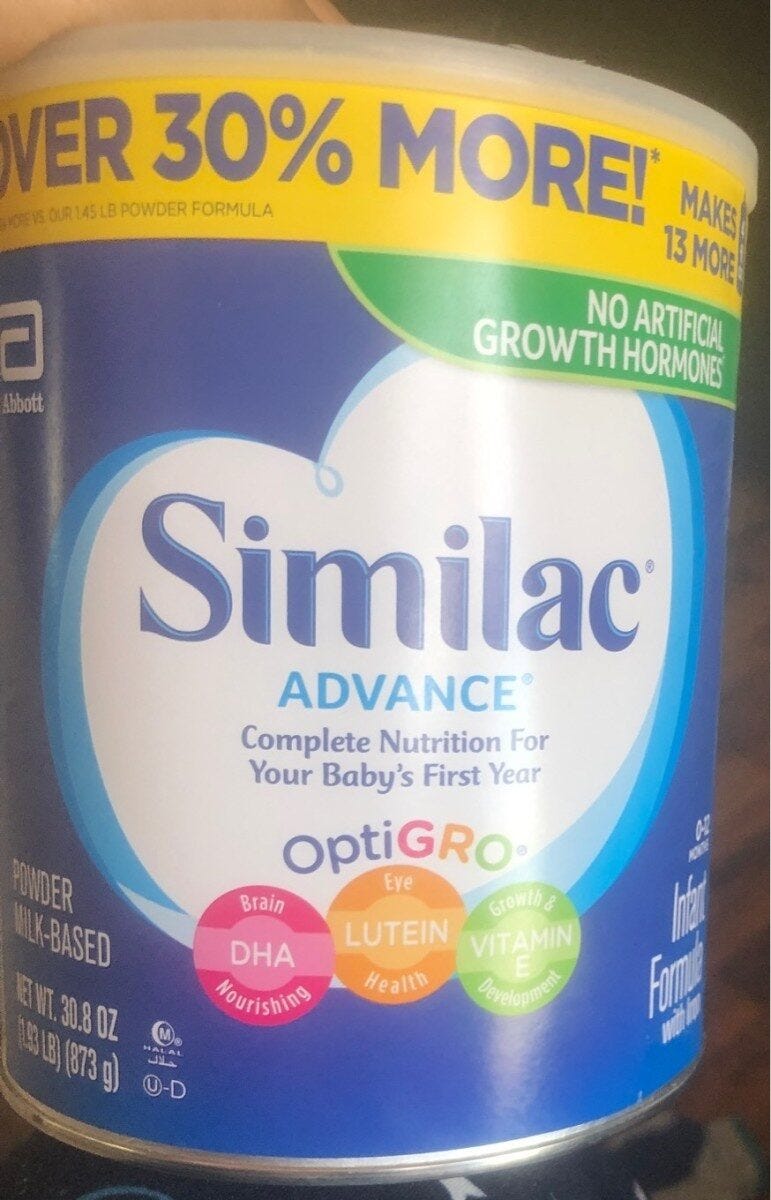

increasing market concentration has become the norm, and not just in high-profile sectors such as e-commerce and ‘social media’. The disastrous shortage of baby formula in the US this spring was itself the result of monopolisation. After Abbott was forced to suspend production over safety concerns, Americans soon realised that just one company accounted for almost half of US supply.

—

(Monopoly is bad for your baby. Image: Open Food Facts. CC BY-SA 3.0))

These problems dons’t get much sympathy from other parts of the world. The whole vaccine patents fiasco, for example, was driven by the World Trade Organisation’s IP rules, which have largely benefitted the corporations of the global North at the expense of the countries in the South.

After four decades of championing globalisation, it is clear that the Davos crowd mismanaged things. It promised prosperity for developed and developing countries alike. But while corporate giants in the global north grew rich, processes that could have made everyone better off instead made enemies everywhere.

Well, the same people you misuse on the way up, you might meet them on the way back down, in the words of Allen Toussaint’s great song. Not that you got any reflection about that at Davos this year, or were likely to. As Stiglitz concludes:

Now that globalisation has peaked, we can only hope that we do better at managing its decline than we did at managing its rise.

2: The simple ugly truths about prostitution

The activist and campaigner Rachel Moran has a direct article on Aeon suggesting that the issues around prostitution are a lot simpler than we pretend they are. She knows of what she speaks, having left home at 14 and spent seven years in prostitution before managing to get back into education again.

Her thesis is simple enough: given what we know about prostitution, and its effects on the women who work in it, there’s no way that we can regard it as ‘decent work’. From her piece, here’s her summary of the International Labour Organisation’s definition of decent work:

Decent work means dignity, equality, a fair income and safe working conditions. Decent work puts people at the centre of development; gives women, men and youth a voice in what they do; the rights to protect them from exploitation; and a future that is inclusive and sustainable.

Well, prostitution breaks these requirements in more ways than we can count, but as she points out, it fails at the most basic level of health and safety.

(Modligiani, ‘Prostitute’, 1918. Via Benoît Prieur/Wikiedia, CC-BY-SA)

And while there’s a whole discourse out there about the validity of sex work as work (even if this is well intentioned) most of the people who articulate this discourse don’t try it out for themselves in practice:

What’s always been particularly galling to me about socially privileged upper middle-class women who popularise these views is that, just like Marie Antoinette before them, they are so far removed from the experience that they cannot relate to it even at a conceptual level. That they are handsomely remunerated to opine on what’s good enough for desperate women is just the spit and polish on the insult.

Amia Srinivasan, for example, says in her book The Right to Sex that sex work “can be better work than the menial work undertaken by most women.’ I think the kindest way I can position Moran’s view of this is to say that she is impatient with it:

I wonder if she has reflected on what that really means: that the female cleaning staff who mop floors and scrub toilets in the University of Oxford, her place of employment, could be better off with their mouths and vaginas full of strangers’ penises.

As she acknowledges, there are women in prostitution who defend it as being work. Research suggests that this depends on whether you are still in prostitution or not. She suggests that thinking of it as work while doing it to make a living becomes “a psychological necessity”.

The truth is, there was no ‘work’ involved in what was done to us in prostitution. Prostitution is neither sex nor work. Sex does not just involve mutuality; it necessitates it. The sex of prostitution is devoid of mutuality, and cash is introduced to fill the breach. In prostitution, the cash is the coercive force, the evidence of the coercion, and the great silencer all at the same time.

It’s a long and compelling piece, and I’m only skating across the surface of it here. She also gives short shrift to the notion that prostitution is “the oldest profession in the world.”

This fiction ignores how incongruent prostitution is when measured against any profession one can think of. A woman who had spent 30 years in academia, for example, could expect incremental increases in salary, in job security, in professional credibility... Prostitution operates in exactly the opposite way. The longer a woman has been exploited in the system of prostitution, the less she is economically valued, the less she’s correspondingly paid, and the less she is esteemed more broadly, both inside and outside of prostitution.

Moran doesn’t offer solutions here, although I was reminded of some research I saw recently—can’t quite place it right now—that none of the measures that were designed to make prostitution “better”, such as regulating brothels or decriminalising women involved in it, but not men, had any good effect on the outcomes.

I think her purpose is different, though: it is, quite literally to shift the discourse so that glib phrases about sex “work” no longer resonate so comfortably on op-ed pages and elsewhere:

The truth for the prostituted woman, though, is that she has not only been sexually abused, but sexually abused too many times to count. The reality of prostitution has been hiding in plain sight for millennia. We all know it, instinctively. That’s why we don’t want our sisters and daughters and mothers in brothels... Controlling what people do sexually is inherently abusive.

j2t#327

If you are enjoying Just Two Things, please do send it on to a friend or colleague.

https://callystarforth.substack.com/p/she-knows-the-game