Welcome to Just Two Things, which I try to publish three days a week. Some links may also appear on my blog from time to time. Links to the main articles are in cross-heads as well as the story. A reminder that if you don’t see Just Two Things in your inbox, it might have been routed to your spam filter. Comments are open.

1: The new shape of work

In my first post based on the talk I gave this week in Cardiff on the future of cities and work, I referenced the model that Geoffrey West developed in Scale to think about how cities work as a system. If you missed it:

In the pre-industrial age, humans would get through about 100 watts a day each. Now, they get through 11,000 watts. West’s model therefore starts from energy and infrastructure, which he says drives social connectivity and social capital. From the interaction between these comes economic opportunity.

And I also used a quote from Servigne and Stevens’ book How everything can collapse:

The paradox that characterises our era… is that the more powerful our civilization grows, the more vulnerable it becomes... To preserve ourselves from serious disruptions to the climate and the ecosystems... we need to turn off the engine.

And I concluded that for a range of reasons—environmental, economic, social—cities were no longer able to reproduce themselves.

When I was doing the research, I revisited West’s triple model, of energy and infrastructure, economic opportunity, and social connectivity, through the lens of what it would require to make this a sustainable system once again.

My version of this diagram looks like this:

(Geoffrey West/ Andrew Curry. CC SA-BY-NC 4.0)

In summary: The urban energy system is based on renewables, not fossil fuels, and this energy is increasingly produced locally. Time becomes more important in the way the economy works. Care—in all its aspects—becomes more important to social connection.

I’m going to expand a little on each of these points here.

Energy

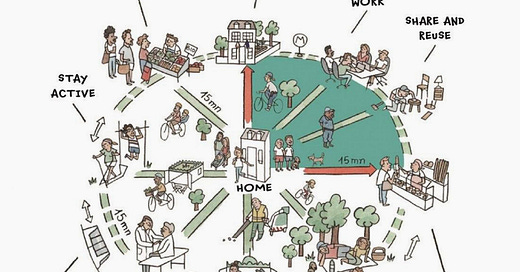

In this new model, energy moves from being globally produced and distributed to being more locally managed, and possibly more locally owned as well. Other current imports become more local as well (to reduce the vast urban footprint) such as food. I’ve heard that supermarkets, for example, are investigating how to use hyroponics in the UK to replace imports of crops currently grown in Spain. There are new types of infrastructure and investment to manage climate mitigation and adaptation. And there are social and political changes designed to reduce the city’s energy consumption—such as the ‘15 minute city’.

(The 15 minute city. Concept by Carlos Moreno/ illustration by (c) Micael)

Time

Time has been a battleground ever since the industrial revolution—‘not a minute on the day, not a penny off the pay’, as the old miners’ slogan put it. From memory, many of the gains in productivity in Europe are being translated into gains in leisure, not more income, and this was true in Britain when we still had productivity growth.

Ideas about the flexibility of the working week and working days have been accelerated by the pandemic, and there are trials of the four day week all over the place, even in Britain.

Time becomes an important element of care—and also enables people to volunteer and engage in other local activities. As mark Fisher wrote before he died,

Most political struggles at the present moment amount to a war over time.

Care

If cities want to be able to function, they need to make sure that care works. This means care for schools and children, health, transport, eldercare, improved mental wellbeing, and so on. Care was defined in a 2020 book by The Care Collective as

a social capacity and activity involving the nurturing of all that is necessary for the welfare and flourishing of life.

It’s striking if perhaps unsurprising how much of this literature is gendered—most of the innovative thinking is being done by women writers and researchers.

But if it is going to be effective, care—in all of its forms—needs to be disconnected from the market: the needs of one don’t align well with the incentives of the other. Things that should be done by ‘guardians’, in Jane Jacobs model, shouldn’t be put in the hands of ‘traders’ instead. In her book on work the sociologist Lynne Pettinger asks:

What would happen if care work, not industrial production, was the start of understanding work?

And it’s worth noting that almost all—perhaps all—of Britain’s current wave of strikes are actually fights about the importance of delivering care, or not. Perhaps that’s one reason why public opinion has largely remained supportive despite attempts by the government and the media to replay the 1970s.

Wot? No AI

I didn’t talk much, or at all about AI in my talk, and since much of the discourse on the future of work is obsessed with this, it’s worth explaining why. One of the issues here is that this conversation is still overshadowed by Frey and Osborne’s 2013 forecast that AI would have an effect on 47% of American jobs, which both missed new jobs that AI might create (as other technology changes have created new jobs), and had a simplistic binary model of how jobs are constructed—as opposed to bundles of tasks that evolve over time.

Generally estimates of impact have been falling ever since, while Frey and Osborne have been adding layers of nuance on this ever since. Osborne and his model was involved in a Pearson/IPPR project which did take account of new jobs found an adverse impact in the range of 5-10%. In a world where time is a new element in the economy, this is a modest impact.

The impact of technology on work is also a function of market power. Digital technology has already wrought destruction on labour markets in the restructuring at the end of the 20th century, when the rate of global population growth and globalisation meant that unions were at their weakest and most workers had little bargaining power.

From this perspective, augmented work—people plus AI—is the mostly likely future.

But there’s also a bigger picture story. Information and communications technologies are the fifth wave of economic transformation since the Industrial Revolution, in Carlota Perez’ model (which also draws lightly on Kondratiev), and it’s coming to an end.

But there’s always a messy overhang, when the innovation that lays the ground for the next technology wave has happened, but it hasn’t yet had market effects. In that phase a couple of things happen. The first is that the technology gets ‘normalised’ in everyday life—think about the equivalent period in the ‘70s and ‘80s around the car, when we saw the evolution of business parks and edge of town stores, a final significant wave of motorway building, and the development of ‘logistics’ as a critical business sector.

The evolution of AI should be read, I’d say, as the equivalent of this.

The other thing that happens is that regulators catch up with the technology, and are finally alert to the risks of adverse externalities.

It’s also worth noting that each of these new waves tends to be distinctively different from the previous one, and that it generates a huge amount of money for the businesses that are in the right place at the right time. There are real questions about where and how AI will make money, which I’m planning to come back to here at some point. But without that potential for rapid sectoral growth, you don’t get a technology wave. And AI is operating in a saturated market.

Living in this city

The city that emerges from this transition is more resilient to shocks. It’s more liveable. It uses data, but as a way to improve its services. It has a richer social and cultural life. It’s probably more decentralised and more distinctive, partly because people who spend more time at home are more invested in their local area. And it probably marks the end of the noisy hype about the ‘global city’.

There’s a fine quote from the 20th century urbanist Lewis Mumford, quoted by Geoffrey West in Scale, that talks about what cities are supposedto be for:

The chief function of the city is to convert power into form, energy into culture, dead matter into the living symbols of art, biological reproduction into social creativity (p373).

This is a much richer version of the idea of the city than the one we have got used to talking about in the past thirty years or so. The focus on GVA (gross value added) and all the other narrow markers of urban success is killing us all.

The slides from the talk can be seen here.

2: Amritsar 2019-1919

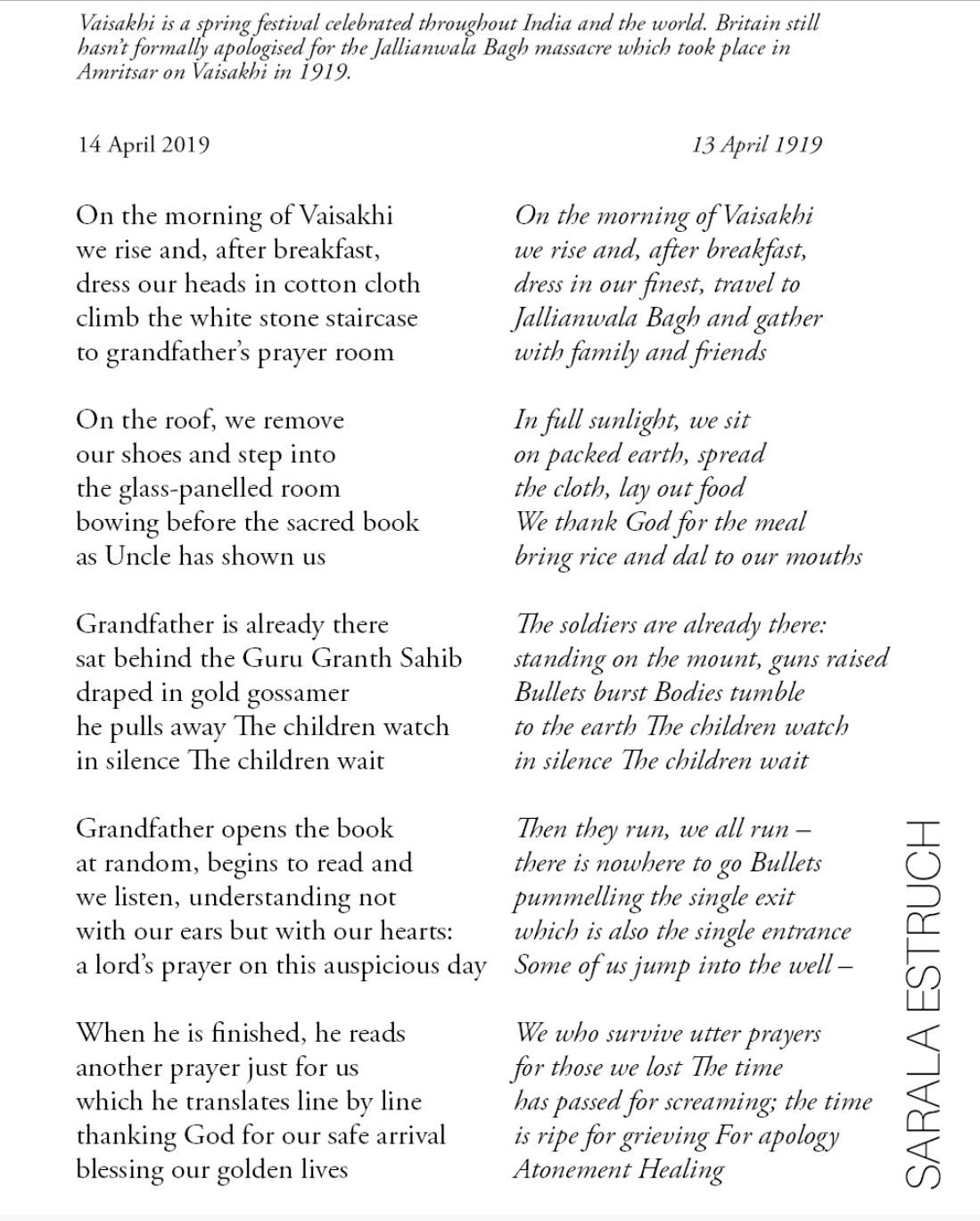

One of the things that futurists sometimes struggle with is conveying differences over time. So I was struck by this poem by Sarala Estruch, from her debut full-length collection After All We Have Travelled, written about the centenary of the Amritsar massacre by the British in India. It was shared by the Poetry Book Society recently.

The layout of the poem is distinctive, and I’ve read this both ways—down the left-hand column, then down the right, and then reading across a stanza at a time—and can’t quite decide which one works best. But I’d probably go down first.

I’ve put this in as an image because the layout makes it impossible to format in Substack.

j2t#422

If you are enjoying Just Two Things, please do send it on to a friend or colleague.