9 December 2021. Transport | Birdsong

Making transport people-centred | Recreating the lost landscapes of birdsong

Welcome to Just Two Things, which I try to publish daily, five days a week. Some links may also appear on my blog from time to time. Links to the main articles are in cross-heads as well as the story.

#1: Making transport people-centred

It was a surprise to find that Rory Sutherland—the behavioural science guru at advertising and marketing agency Ogilvy—had co-written a book on transport. He and co-author Pete Dyson write about it in Behavioural Science.

For centuries, transport has been a battle of ideologies: the utilitarians versus the romantics... We aim for a more balanced position. We argue that society’s present focus on utilitarian efficiency has run its course and that the romantic view of travel needs to be updated to make transport simpler, more inclusive, and sustainable

—

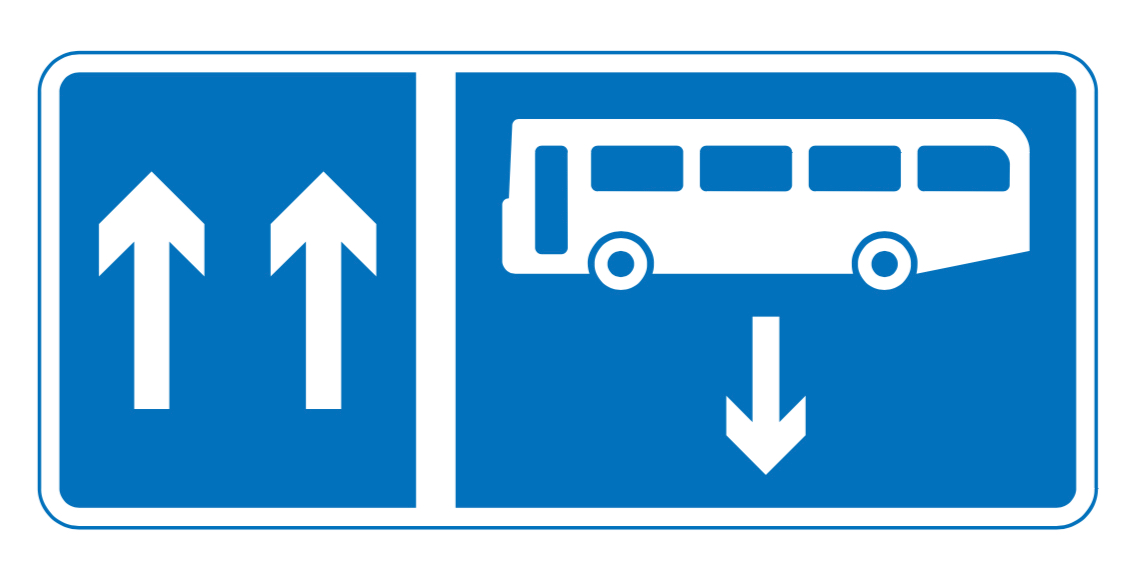

(UK traffic signs. gov.uk)

There’s a bit of a conceit in all of this. They construct a version of a traveller they call Homo transporticus—with an explicit nod to Home economicus, the rational calculator version of people that neo-classical economics requires to make some of its models work.

Homo transporticus is naturally selected to use modern transportation, with abilities that include a full awareness of the modes of travel available, an encyclopedic knowledge of routes and timetables, the ability to navigate them without hindrance, and the ability to compare two options and always choose between them in a way that a planner would consider to be rational.

This person, they say, is a construction of transport designers, which seems a bit off the mark. Transport designers actually spent the last forty years of the second half of the 20th century privileging car users over other travellers, before they started to notice all of the costs involved in doing this.

But we can let that slide by for the moment. They’re on much firmer ground when they look at the problems that modes of travel cause for many people:

Across the world there are more than one billion people living with severe or moderate disabilities. In the United Kingdom one in five people has a condition that makes travel challenging. This is more than just a physical problem in getting from A to B. In 2019, four in five people with a disability reported feeling stressed or anxious when traveling; half felt this way on every journey.

And as our populations age, we can expect the number of people with disabilities to increase.

Even pre-pandemic, travel behaviours were changing. The article has a list of bullet pointed UK data that suggests that we may be travelling less. Here’s a few of those bullet points:

The average household is traveling less. Total trips per person per year in the United Kingdom had declined 8 percent since 2002.

Are we past peak car? Vehicle mileage per capita has declined since 2012, and in the United Kingdom it has fallen 12 percent since 2002. Comparing 1995–99 with 2010–14 there has been a 36 percent drop in the number of car driver trips per person made by people aged 17–29...

Transport is not all work. Shopping and personal trips declined by 30 percent between 2011 and 2019, while leisure trips were down 20 percent...

Workers don’t take the train … season ticket sales in the United Kingdom declined by 17 percent from 2016 to 2019, while rail usage overall increased by 2.8 percent.

… or the plane. United Kingdom business travel has been stagnant for the past 10 years according to Department for Transport statistics.

But one thing that is increasing is emissions from transport, responsible in the UK for more than a quarter of all carbon emissions. The Prime Minister’s claim that we won’t need to change what we do to get to Net Zero, because it will be fixed by technology, unfortunately isn’t true. Electric cars still have embedded emissions. So something will have to change:

For transport, (getting to net zero) includes reducing the amount we travel and making choices to adopt less polluting alternatives. Unfortunately, swapping out old technologies for new is not sufficient: our lifestyles and travel choices will also need to change. Right now, these can be presented as choices to make a positive difference. Effective change now can avert a future in which many aspects of mobility may be constrained by laws and regulations governing everyday life.

And as it happens, I was involved in writing a set of long-term transport scenarios back in 2005 that included this as one possible future. It’s not a particularly attractive world. But:

Fortunately, when it comes to environmental change, transport has the time and the insight needed to prepare a more balanced set of people-friendly responses. This will involve upstream changes as old technologies are replaced, midstream changes involving regulations and requirements for organizations, and finally downstream changes to how individuals and communities are persuaded to update their travel choices.

That, in part, is where the behavioural science comes back in, as far as Sutherland and Dyson are concerned. I’m sure it will help. But there are deeper reasons why transport is so hard to fix. People can’t make better choices if the transport options don’t exist. And that close link between Home transporticus and Home economicus still exists in government, where it is encoded into the models that the Treasury uses to assess investment in transport schemes, as the recent history of UK rail investment demonstrates.

#2: Recreating the lost landscapes of birdsong

Researchers at the University of East Anglia have been busy reconstructing the soundscapes of birdsong, as a way of showing what we have lost as the number of birds has declined. Simon Butler and Catriona Morrison have an article in The Conversation on how they have set about doing this.

In general, we don’t have good recordings of previous soundscapes: they need to be reconstructed:

- They start with annual bird monitoring data collected by volunteers through European and American bird surveys in over 200,000 sites across Europe and North America.

- Then they translate the monitoring data into soundscapes by combining them with sound recordings for individual species downloaded from Xeno-canto, an online database of bird calls and songs.

- They assign a sound file for every bird that was counted in the surveys.

- This then constructs a composite soundscape for each site, which should represent what that location would have sounded like when the volunteers were there doing their annual bird count.

What this sounds like can be heard in this link: a 1998 soundscape from Bromsgrove, in the English Midlands.

https://cdn.theconversation.com/audio/2333/uk-bbs-square-1998.mp3

That’s not the end of the peocess. Finally, they assign ‘acoustic markers’ to show how the acoustic energy and diversity in a site has changed over time:

Our results reveal a clear, continuous fall in the acoustic diversity and intensity of soundscapes across Europe and North America over the past 25 years, suggesting that the soundtrack to our spring is becoming quieter and less varied.

In general, we found that sites that have experienced greater declines in the number of species or total number of individuals counted also show greater declines in acoustic diversity and intensity.

When you put it on a spectograph, it looks like this.

(A spectrogram of multiple bird species singing. Source: Butler and Morrison, via The Conversation)

There’s more to this: the loss of some species, such as the nightingale, has a much bigger impact on the soundscape than, say, a gull species.

They hope that this process will make the sense of biodiversity loss more tangible:

Nature’s orchestra is fast losing both players and instruments. By translating the hard facts on biodiversity loss into tangible images and recordings, we hope to heighten awareness of this tragedy and encourage support for conservation through protecting and restoring high-quality natural soundscapes: so people can access, enjoy, and benefit from nature again.

One of the problems about biodiversity loss is that it is a slow process, and humans aren’t that good at noticing slow losses. It’s a complex and apparently labour-intensive process. But it heightens awareness of the gaps that have appeared in our world with the Sixth Great Extinction. And it may also be a way of making solastalgia tangible, so we can quantify environmental loss rather than just sensing the gap.

Update: I wrote here recently about Apple and the right to repair. There was some scepticism about how genuine Apple’s announcement was. IEEE Spectrum has an interview on this with the co-founder of iFixit Kyle Wiens, who discusses some of the ways that Apple could still make repair difficult.

j2t#224