9 August 2022. Cities | Economics

The illusion of the Saudi city in the desert.// The economics of social justice

Welcome to Just Two Things, which I try to publish daily, five days a week. Some links may also appear on my blog from time to time. Links to the main articles are in cross-heads as well as the story. A reminder that if you don’t see Just Two Things in your inbox, it might have been routed to your spam filter.

1: The grand illusion of the Saudi city in the desert

There have been reports floating around for a while now of the 100-mile linear futuristic city planned for the Saudi desert, and last week the plans were officially revealed when Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman opened an exhibition in Jeddah. The city is as described:

THE LINE... is 200 meters wide, 170 kilometers long, and 500 meters tall. It will eventually house 9 million people and have a 34-square-kilometer footprint... THE LINE imagines a future without streets, cars, or emissions. It will be powered entirely by renewable energy and prioritize health and well-being over transportation and infrastructure.

It is bin Salman’s private project. The name Neom—the over-arching name for the project—comes from the first three letters from the Ancient Greek prefix neo-meaning "new"—while the fourth letter is from the abbreviation of Mostaqbal, an arabic word meaning "future". This all reminds me of the complaint made in the 1920s that nothing good would come from television, because the word was half Greek and half Latin.

(Source: Neom)

But there’s a bigger problem than that. There’s a reason why—over the course of 6,000 years or so of human history—that cities have tended to take a circular shape. Broadly, that reason is about reducing distance and therefore energy use. A city that is 170 kilometres long and only 200 metres wide is going to be hard to move around, despite the promise of high speed trains.

And it is fair to say that now the plans have been published, pretty much everyone hates it. Or, more accurately, everyone who lives outside of Saudi Arabia, since this is very much Mohammed bin Salman’s pet project, and he’s not fond of critics. In this post, I’m just going to pick out some highlights from the coverage, from a range of different magazines.

Fast Company spoke to Brenda Case Scheer, an American urban planning professor:

Scheer is skeptical of much of that vision, particularly the prospect of humans occupying the deep reaches of a city measuring just 650 feet wide.

“It’s an extremely dark vision. I mean that both literally and figuratively,” Scheer says. “You can’t have a breath of fresh air, you can’t grow a daisy on your front porch, you can’t even have weeds in the cracks of the sidewalk. It’s like an airport.”

Some of the promotional material suggests that some light will get in, but that one benefit of the enclosed space are that it enables the climate to be controlled.

Despite the claims about sustainability, the embodied carbon in a new city on this scale is colossal:

Scheer argues that the embodied carbon required to build such a project would vastly outweigh whatever sustainability elements it implements, also noting that such a project would be unlikely to last long enough to even live up to its goal of becoming a city. “It’s a building, and buildings don’t last that long,” she says. “The bigger the building, the faster it becomes obsolete.”

Some of Fast Company’s interviewees located Neom in the history of architecture—there have been linear urban schemes before, if not on such a scale—and The Architect’s Newspaper went into this history in more detail:

Many commented on the formal and visual similarity the megalomanic vision has to an array of linear-city precedents in the history of architecture, from Michael Graves and Peter Eisenman’s proposal for a linear New Jersey in 1965; to Rem Koolhaas’s infamous graduation thesis, “Exodus, or the Voluntary Prisoners of Architecture” from 1972; or, most obviously, to Superstudio’s late 1960s critique in the form of the Continuous Monument.

In this context the writer of this article, the architectural historian and architect Eliyahu Keller, reminded his readers of Marx’s famous line about history repeating itself first as tragedy, then as farce. His piece discusses the whole project as a form of futures—summarising brutally, he characterises it as what I’d call a ‘used future’ presenting itself as utopianism.1

It’s quite an academic piece, but it conjures up a complex tension between Neom’s promise of sustainability and the facts of the climate crisis. It also challenges the claim that the city is somehow going to leave nature ‘untouched’.

“For too long,” (the Neom presentation) goes, “humanity has existed within dysfunctional and polluted cities that ignored nature.” In response, NEOM offers not only to “protect” nature but to “enhance” it. This nature, we should note, is the Rub’ al Khali, or the “empty quarter”—one the largest sand deserts in the world: a landscape that is anything but empty, which is in fact inhabited by various tribes as well as plants and animals.

Already, people living in the path of the city have been displaced, one even killed.

Bloomberg, as you’d expect, prefers to follow the money. It compares the project to the distressed Chinese property developer Evergrande. The comparison isn’t far-fetched. Neom is supposed to house nine to ten million people”: Evergrande says it has already housed 12 million.

It’s spent $89 billion doing this, compared to Neom’s projected budget of $320 billion. But since Chinese construction costs run at about 40% of Saudi costs, the orders of magnitude are about right.

Of course, Evergrande is currently in default:

if you were to choose a model for Saudi Arabia’s future it would probably not be a distressed developer from a Chinese property sector that S&P Global Ratings thinks may be headed as a whole toward insolvency.

But the reason for the comparison was that for much of its history Evergrande was an efficient user of capital and had a successful business model, effectively underwritten by pre-sales. The reason it ended up in default was that it followed government directives to build more extensively in China’s Tier 3 cities, where people largely don’t want to live.

If a property developer focused on Chinese Tier-3 cities can turn into a disaster, though, how should one rate the prospects of a brand-new city in a desert distant from both oilfields and the unique pilgrimage destinations of Mecca and Medina? Neom’s vision of zero-carbon living for the 21st century is seductive — but if it is achieved, the economic prospects of the nation that’s using billions in oil money to build it are grim indeed... If Neom is intended more as a rebranding exercise for a country determined to sell every last drop of its crude, there are far cheaper ways to recalibrate your public image.

At best, it seems like a vast multi-billion bet on Saudi’s oil revenues, and an ego-driven one, just before they become stranded assets. And when you put it like that, says the Bloomberg columnist David Fickling, there are better infrastructure projects to spend the money on:

The lesson Saudi Arabia should draw from Evergrande is that infrastructure and property development work best when they follow the people, rather than trying to lead them... Mohammed bin Salman has his work cut out fixing his country’s sprawling, congested cities for a population of some 36 million expected to grow by a third by 2050.That task is hard enough amid signs that oil demand may go into decline, even as Saudi Arabia’s supply potential appears to be maxing out. That would be a far better use of the kingdom’s cashflows than a vast folly in the desert.

2: Economics and social justice

The economist Diane Coyle reads voraciously and seems to take good notes, since she posts frequent short reviews of much of her reading on her blog. A recent post is about A Political Economy of Justice, a collection of essays based on a conference, edited by Danielle Allen, Yochai Benkler, Leah Downey, Rebecca Henderson and Josh Simons. As she says, that’s an impressive group of editors.

The intro makes the case for considering capitalism as a multi-level system whose economy is institutionally embedded, reflects power relations, depends on social norms and instantiates certain values. It thus argues that neoliberalism as an economic ideology ignores these contextual aspects, claiming an impossible universalism... The editors also argue strongly for the discussion of social justice and the values of the capitalist economy to focus on the organization of production as well as – or rather than – the distribution of income and consumption.

The essays range from ‘beyond GDP’ to ‘the US prison-industrial complex’, and have a strong US focus. She also notes that “there’s a clear progressive slant”—although given how far right neoliberal economics and politics has taken our societies, certainly compared to much of the 20th century, it would be hard not to have a progressive slant.

One section, however, pulled me up:

There’s also some discussion – interesting to me! – of the implications of economic measurement, the definitions and metrics particularly GDP, for social justice: “Contemporary theories of justice have given these questions little sustained attention.”... The chapter on this issue (by Julie Rose) takes the perspective of a history of thought about idea of the stationary state, invoking Mill, Keynes and Rawls. It argues for an alternative aim: “To fairly and reliably expand people’s opportunities,” and paints GDP growth as a subsidiary aim.

Her concern with this is that it’s not “actionable”, although I’d disagree with that from a policy point of view. But the sentence that pulled me up was this:

I must say I’d expected a traditional ‘degrowth’ argument and was relieved to find Rose doesn’t fall in to that trap.

The reason it had this effect on me was twofold. The first is that Coyle is one of the most reflective economists writing at the moment. Her book on the limits of GDP is first rate; she was writing about “the economics of enough” more than a decade ago, a long way ahead of the crowd.

The second is that if you’re going to discuss degrowth in this context, I think you need to spell it out rather than batting it into the corner in this pejorative way.

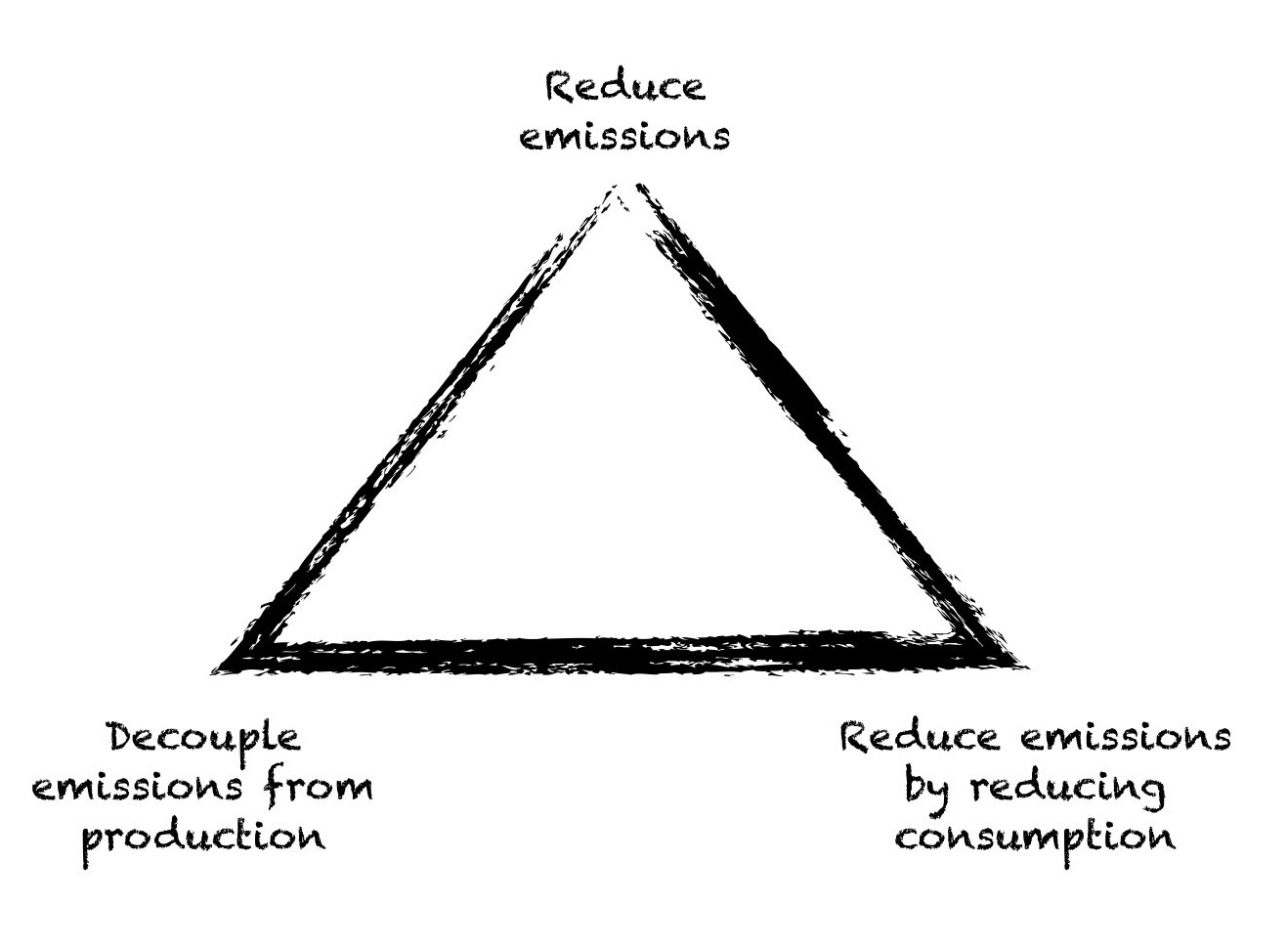

Because: there’s a kind of triangle here. At the top, we need to reduce carbon emissions rapidly. At one leg, we could, maybe, decouple emissions from production, in the affluent world (which enables growth to continue). Or, at the other leg, we could reduce consumption, and therefore production, which is essentially the degrowth argument.

(Source: Andrew Curry. CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

Politicians (and some economists) like the decoupling argument, because nothing has to change. Unfortunately, so far the evidence that it works is thin. It’s technology as magic bullet. There are some small effects, but nowhere near enough to reduce emissions at the scale or speed we need to avoid catastrophic climate change.

So we need to reduce consumption. Actually, there are arguments that suggests that this is good for us, in a number of ways, including our mental health, especially if it is accompanied by some redistribution. That’s probably a piece for another time (I have recently bought Jason Hickel’s book on this theme, so will maybe review it here in due course).

But it did make me think that just as the title Limits to Growth produced a poisonous and uninformed ideological attack—a defensive response mechanism from the system, perhaps—that one of the problems of the idea of “degrowth” is actually the name.

We are living in a system that has been predicated on the idea of economic growth for 200 years, and which has had it formally baked into its political economy, through measures such as GDP, for 75 years. If you’re trying to change a system, it’s best not to attack its core belief system. Time for branding people to do something useful and come up with a new framing for the idea of the rich world consuming less, I think.

j2t#357

If you are enjoying Just Two Things, please do send it on to a friend or colleague.

Jose Ramos suggests the used future is “an image or idea of the future that someone else created in some other context, but to which we are unconsciously holding on to, blinding us to other more authentic and empowering ideas of the future.”