Welcome to Just Two Things, which I try to publish daily, five days a week. Some links may also appear on my blog from time to time. Links to the main articles are in cross-heads as well as the story.

#1: Making rewilding more visible

When I started Just Two Things I didn’t expect to see so much in my feeds on rewilding. But it’s definitely there, and this suggests that the biodiversity crisis—which has been overshadowed by the climate crisis—is starting to get the attention it needs, if belatedly.

At her Inkcap newsletter, Sophie Yeo reports on an imminent campaign to persuade the Royal Family, the Church, and Oxbridge colleges to rewild their lands. (Inkcap focusses on nature, ecology and conservation in the UK.) To be sure, these are all large landowners. But they have also been selected by the campaign, Wildcard, for their symbolic importance, as co-founder and artist Clarice Holt explains:

“The Royals have stewardship over land and people. The Church provides moral, religious and spiritual guidance. Oxbridge is bringing up the next group of people who are probably going to rule the country, and are supposed to shape young people’s ideas of how things are supposed to work,” she says. “If those household names were to shift their perspectives on rewilding, they would bring a lot of people with them and would set the gold standard for rewilding as a general concept.”

Wildcard, described as a group of campaigners, artists, and ecologists, seems to be drawing on other recent campaigning ideas in its approach—the less combative elements of Extinction Rebellion, on the one hand, and divestment campaigns on the other.

At the XR end of the spectrum:

From the students of Oxbridge and the parishioners of the Church, the co-founders of WildCard hope to recruit an army of volunteers that will persuade their institutions to rewild thousands of acres of degraded land. Its activism will be “as respectful as possible” and focus on “nice family-friendly stuff”, says Holt – she envisages people planting WildCard flags on degraded land, medieval parades and church choirs performing rewilding-themed songs.

But talking to owners also matters. Another co-founder, film-maker Josh Scott-Halkes, observes that when pension funds were approached by divestment campaigners, it was often the first time that anyone had asked them to consider the impact of their portfolios:

In targeting the Royals, Church and Oxbridge, WildCard has been guided by the tactics of divestment campaigners, who have sought to persuade big institutions – including universities, faith groups and pension funds – to drop their investments in fossil fuels. “They found that pension funds had never received a single email about climate change, even though they’re investing billions in it,” he says. Similarly, “big landowners are just not used to people requesting things en masse. A respectful, creative, inviting approach could achieve big change.”

I’m not sure how much change they’ll get out of the Royal Family, but the Church of England and some Oxbridge colleges have been responsive to climate divestment campaigns. And I like the way that their ‘family friendly’ campaign ideas would escape the constraints of Priti Patel’s repressive Police, Crime, Sentencing & Courts Bill.

Rewilding does affect existing employment, but is likely to create more rural jobs, and often better ones, and ecological campaigners need to find a way to talk about this. There should be more to moorland than grouse-shooting, as indie band The Lounge Society suggest in their song ‘Burn The Heather’.

One final thought: if you’re trying to engage with large landowners who are also pillars of the state, the Ministry of Defence owns around 500,000 acres and has rights over another 500,000. Although some of this is already fairly wild.

#2: Resisting the attention economy

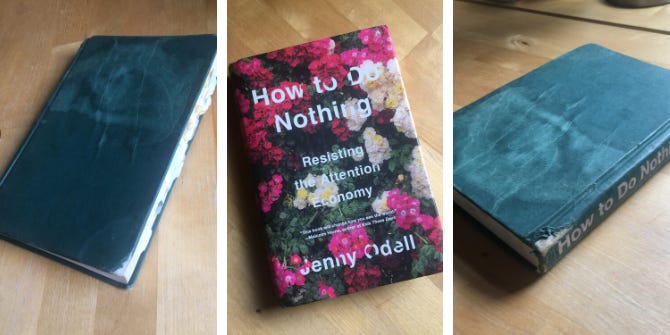

There is a self-deprecating review on the LSE Books Blog of Jenny Odell’s book How to do Nothing: Resisting the Attention Economy. The reviewer, Christine Sweeney, admits she is hopeless at doing nothing, and offers the fact that she agreed to review the book while also busy on other projects, rather than just reading it, as evidence of this. The review comes with images of the battering the book got from having been squeezed in among her other tasks.

(Image: Christine Sweeney)

Its author, Jenny Odell, is a Millennial, that generation born just as the internet became the dominant idea in society. She’s worked for digital businesses and lectured about them:

Having worked in digital marketing, her understanding of how data can be used to understand humans not as humans, but rather as consumers, informs her art, a desire to take stock of the rampant changes we have seen over the past decade and a half… From this position, she invites readers to consider the possibility that you can get a lot, potentially more, out of observing rather than adding to the world around us.

What gets in the way of observing, of letting the world come to us? Well, capitalism, of course:

‘A colonization of the self by capitalist ideas of productivity and efficiency’, this idea that ‘we should all be entrepreneurs’. Indeed, those who subscribe either by necessity or desire to the cult of hustle in this gig economy might respond: ‘why shouldn’t we all be entrepreneurs?’ Odell’s clear writing, asking us to question our unwitting acceptance of cultural and economic phenomena like mass-entrepreneurship, underscores its absurdity.

Sweeney has rather more time for this critique than she does for those of the prodigal former tech bros like Tristan Harris, who—having been heavily involved in creating the social media businesses that now dominate—now critique their effects without also critiquing their structure. And it is the structure of the attention economy distracts us from ourselves as people. In making this critique, Odell’s book hovers somewhere between philosophy, psychology, and self-help:

When we choose our attention over algorithms, by turning on the radio rather than our curated playlist, for example, ‘we decide who to hear, who to see, and who in our world has agency’. Redirecting our attention away from what the algorithms suggest for us, as perfect as those songs or matches might seem, we can welcome back context. Context allows for change, yet how one presents oneself on social media creates an inability to publicly change our minds. Think of the ways in which public figures are called out when they make statements that contrast with posts they made on social media from ten years ago. Without context, there is little space for the nuanced ways we change and evolve.

j2t#072

If you are enjoying Just Two Things, please do send it on to a friend or colleague.