8 March 2024. Literary futures | Innovation

Using literary futures to open up imagination // How Apple blew $10 billion on a prototype car [#550]

Welcome to Just Two Things, which I try to publish three days a week. Some links may also appear on my blog from time to time. Links to the main articles are in cross-heads as well as the story. A reminder that if you don’t see Just Two Things in your inbox, it might have been routed to your spam filter. Comments are open. And—have a good weekend!

1: Using literary futures to open up imagination

I’ve been aware of the concept of “literary futures” since I attended a workshop at Lancaster University’s then Institute for Social Futures in early 2020. Emily Spiers ran a narrative futures component in an all-day workshop that was, presciently, about biohazards. That work has been taken further by Emily’s former colleague Rebecca Braun, now at the University of Galway, and she has just published a paper called ‘Literary Futures: Harnessing fiction for futures work’ with two Galway colleagues.

It’s an interesting approach, and I am going to point to some highlights here. The whole paper is in front of the Futures paywall. But a bunch of disclosures here: I have worked with Rebecca and met her two colleagues; I reviewed an early draft of this paper, and made a modest methodological suggestion, generously credited in the paper, as the approach was starting to evolve.

The paper documents the approach and has some quantitative analysis of some of the workshops involved in developing the method. I’m going to focus on the first part of this here.

But let’s start with the core claim of literary futures:

Central to the Literary Futures method is the notion that literature itself – as both an object of study and a process of creative engagement – should be considered a core tool for imagining and acting upon social futures.

In doing this, it is positioning itself in the group of futures methods that has emerged into the mainstream since the 1990s, which are informed by culture, values, politics, and, come to that, agency, as against the more technocratic and positivist futures of the business and military world.

But: it’s not about using science fiction or other futures-oriented texts. Instead:

(I)t is grounded in those formal and structural features of literary texts that underpin the fundamental activity involved in imagining alternative worlds from various perspectives, and in applying these in a practical way to engage in futures thinking: telling a story in a linguistically and conceptually engaging way that uses the power of metaphor, imagery, character and plot to allow both projection into an alternative time and place and reflection back on the reader’s contemporary reality.

(Don Quijote, by Honoré Daumier, circa 1868)

And so the Literary Futures method has, in effect, headed in exactly the opposite direction from science fiction, to texts that are part of the Western canon. (I imagine that people using it in other cultures could draw on their canon instead). In fact, the example given in the article is Cervantes’ Don Quixote.

(Quixote’s) world is not bound by traditional linear chronology, offering the reader instead space to imagine alternative (social) worlds, holding a variety of perspectives in view simultaneously. On multiple levels, then, Don Quixote in fact acts as a meta-narrative for foregrounding both the challenges and the opportunities of doing futures work.

The paper describes a workshop approach to using literary futures, and there’s probably just enough here to encourage people to try this at home, or at least in a pilot workshop of their own. It unfolds in three stages:

Character development

Worldbuilding

Integrating futures techniques

Character development

The literary futures method starts with character, not with worldbuilding. The rationale for this is both theoretical and practical. Theoretical:

characters play an important role in enabling the reader to engage with diverse and multiple perspectives and with the felt experiences of others and their interpretations of the world. This offer of “inner dimensions” makes literary fiction a rich resource for experiential approaches to futuring.

In practice, it works like this:

This is designed to be an empowering experience that involves making a series of quick decisions... The characters are developed through an open process, with a set of standard character development questions acting as a template to get started as opposed to a rigid set of instructions. These characters are not being designed to a specific end or in relation to a pre-determined future scenario. Rather, the emphasis is on creating a well-rounded character, shaped by a backstory and values, and an understanding of how they behave with and interact with others.

From a process point of view, it is worth noting that the characters are built individually by the participants, not in discussion with the other members of their group.

Worldbuilding

The worldbuilding stage then uses the characters and their interaction to build the world(s).

Participants are asked to consider where their characters are, what they are doing, who they are with and what interactions are taking place. This activity is supported by a prompt that involves putting a group of characters together (c. five characters/participants) at a given point in the future and providing one significant piece of information about this future world.

The prompt is broad: the example given in the article is: “It is 2040 (or date 20 years into the future), and the world is wholly reliant on renewable energy”. It is then down to the characters to find their way in this world together.

Both as a participant in Emily Spiers workshop and running a workshop based on the method—building images of Piccadilly in 2100—I found this approach profoundly liberating. You can get some genuinely open futures as the characters start to mesh into their worlds. In the Piccadilly workshop, we had a baby with super-cognitive powers that had escaped from its parents, for example. Perhaps this is because:

At this point in the workshop, an ‘anything goes’ approach is adopted and participants are encouraged to think creatively around any apparent stumbling blocks in their story (for example having created a medieval character or having a set of characters scattered around the globe).

Integrating futures techniques

The final step is trying to bring the worlds to life in practical terms. The method uses Lum and Bowman’s Verge framework, which is an ethnographic approach to building out how a world works in practice. You can read that at the link, so I won’t expand on it here, except to quote the article briefly:

Of particular value here is the focus on (human) experience under six domains: Define, Relate, Connect, Create, Consume, and Destroy... Incorporating this futures technique moves the Literary Futures method from an exercise in pure imagination to one that offers insights into the concrete and practical nature of the worlds that are developed. This makes these worlds more tangible, bringing them to life through the eyes of multiple characters.

The second futures tool that gets deployed is backcasting, to work back from their emerging future world to the present and visualise some of the things that might have happened on the road to this particular future. Again, this opens up discussions about the topic under consideration from a range of different perspectives.

My experience of the method suggests that it produces vignettes—stories with a clear centre of gravity that allows the world to come into focus—rather than full scenarios. Equally, though, that also means that people think more freely about the future, and starting from the characters before dropping them into the future is particularly liberating here.

When Emily Spiers ran the workshop in 2020, she opened with a quick game of Consequences, with a starting prompt for each table based on the workshop theme, with each sheet going round the room. This created energy in the room, built up a repertoire of ideas, and freed up thinking. When I ran my Piccadilly workshop, I repeated the trick and it had the same effect.

2: How Apple blew $10 billion on a prototype car

I’ve been trying to get my head around the idea that Apple spent about $1 billion a year for about ten years on trying to develop a self-driving car, never got close, and then—without ever having admitted that they were working on such a thing, shut the project down. And let’s face it: there are a lot of other things you could spend $10 billion dollars on.

But the story seems to be a lesson in how not to manage an innovation project. Because in ten years, and with $10 billion, they never managed to get a prototype to drive on a public road.

There’s a long—perhaps too long—piece at Bloomberg trying to understand what happened. (Thanks to Charles Arthur’s daily tech blog for pointing me to this archived version.)

So trying to get past the tedious detail of the internal politics, the story seems to have gone like this. Once upon a time Steve Jobs mused that Apple should think about cars, but gave up on the idea to focus on the iPhone. (Apparently Apple considered buying General Motors after the financial crisis for cents on the dollar, but decided that the optics wouldn’t be good.)

In 2014, Tim Cook, now Apple CEO, came back to the idea. Apple was looking for new long-term revenue streams it could apply its technologies to. One of the attractions, apparently, was that they thought the car sector was poorly managed, mixed with a quite a lot of hubris:

Apple executives weighing whether to enter the market joked with one another that they’d rather take on Detroit than a fellow tech giant: “Would you rather compete against Samsung or General Motors?” ... To its supporters, the idea of getting into automobiles had the potential to be, as one Apple executive puts it, “one more example of Apple entering a market very late and vanquishing it.”

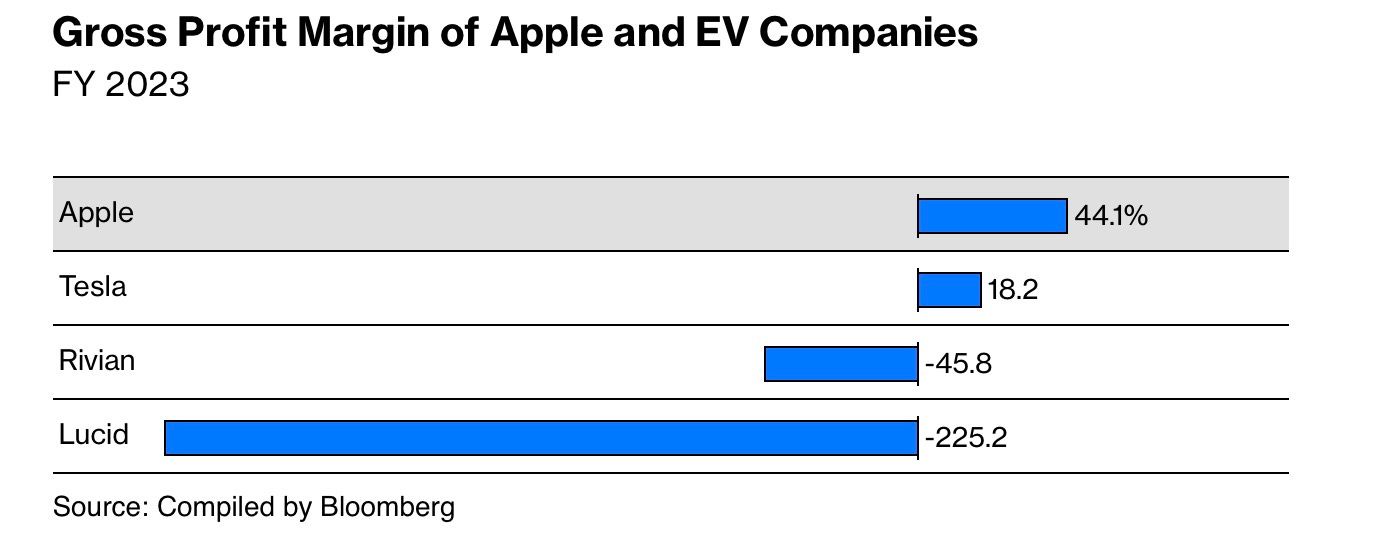

Before they started their own car project, they considered buying Tesla, then valued at around $30 billion, or a thirtieth of its current value. Apple’s Chief Financial Officer, Luca Maestri, who had previously been the CFO of General Motors in Europe, was sceptical. The car industry was a much lower margin business than Apple was, and he didn’t see that changing.

(Source: Bloomberg)

Anyway, the car project proceeded as an internal project. It was given a codename and talent was hired:

Apple’s newly minted hardware chief, Dan Riccio, received approval to start building a car engineering team, and he hired hundreds of engineers from the auto industry for what came to be known as Project Titan. The team working on the car was called the Special Projects Group.

All the same, there were internal disagreements from the start. Some of these were about whether Apple should be bothering at all, and the resources involved, but others were about if the company should try to reinvent the entire idea of the car around full self-driving autonomy, or build something that looked and felt more like a car.

Apple’s then chief designer, Jonny Ive, seemed to be on both sides of the argument, but couldn’t resist the opportunity to design the full self-driving version:

Under Ive, the microbus design emerged. The interior would be covered in stainless steel, wood and white fabric. Ive wanted to sell the car only in white and in a single configuration so it would be instantly recognizable, like the original iPod he’d designed. At one point, the group briefly discussed a more traditional SUV-like design, as well.

Only in white... you can have any colour you want. And, say the Bloomberg reporters, Mark Gurman and Drake Bennett, the team kept having ever wilder ideas, redesigning the interior, realising they weren’t good ideas, and abandoning their redesigns.

Here the company cultute probably didn’t help. The article quotes a senior exec who who tell the team that

the company should build “the first bird,” not “the last dinosaur.”

(From Jonny Ive Parody on Twitter via Know Your Meme)

By 2016, they hadn’t got far, and Bob Mansfield, in semi-retirement, was persuaded to come back into the company to sort it out. Mansfield had led the hardware development of the MacBook and iPad.

He decided to focus Apple’s effort on the autonomous software system, and leave the dirty business of building cars to other people. There were layoffs from the project team. But Mansfield also persuaded Doug Field, a former Tesla executive, to come in and take over the project.

By 2020, Field was able to run a demo of an autonomous vehicle to Apple’s senior executives at a former Chrysler test track in Arizona that Apple had acquired.

The prototype, a white minivan with rounded sides, an all-glass roof, sliding doors and whitewall tires, was designed to comfortably seat four people and inspired by the classic flower-power Volkswagen microbus. The design was referred to within Apple, not always affectionately, as the Bread Loaf.

This was designed as a fully autonomous vehicle—Level 5, in the scale of these things. (The current Tesla vehicles are at Level 2). It would drive

entirely on its own using a revolutionary onboard computer, a new operating system and cloud software developed in-house. There would be no steering wheel and no pedals, just a video-game-style controller or iPhone app for driving at low speed as a backup.

It worked well on the test track, and Cook and the others loved it. But there was a catch. Field told them that there was a lot of work to be done before the vehicle could run autonomously on the road. He proposed scaling back the company’s ambition to Level 3, in which

“The vehicle can perform most driving tasks, but human override is still required.”

But Apple wanted Level 5, and a year later Field moved on to Ford. Work continued under Kevin Lynch, and the design kept changing. At some point, the company decided to scale back their ambition to Level 2. A steering wheel and pedals were added to the prototype. On February 27, Cook finally killed the project.

(T)he company had ended up where it began a decade earlier, with a product little different from what was already on the market and a basic, not-great self-driving system... When asked, he (Lynch) made clear that true autonomy might be another decade off. He seems to have finally convinced Apple’s leadership that that was a problem without an affordable or reliable solution in the foreseeable future.

Reading the whole piece, it seems that Apple’s real problem here was a combination of technological over-confidence, not enough focus on what they were trying to do and why, and too much money.

“There are a lot of roads you can take when you have a lot of really smart people and a very big budget,” says Reilly Brennan, a partner at the transportation technology venture fund Trucks VC. “But Apple never had the ability to make a bunch of specific decisions to lead them one way or the other.”

j2t#550

If you are enjoying Just Two Things, please do send it on to a friend or colleague.