8 June 2022. Climate | Stupidity

Getting unstuck from climate change. // Businesses are getting more stupid.

Welcome to Just Two Things, which I try to publish daily, five days a week. Some links may also appear on my blog from time to time. Links to the main articles are in cross-heads as well as the story. Recent editions are archived and searchable on Wordpress. And a reminder that if you don’t see Just Two Things in your inbox, it might have been routed to your spam filter.

1: Getting unstuck from climate change

I’ve been dipping into a recent collection by the theological think tank Theos reflecting on COP26 and its aftermath. It is edited by Theos’ head of research Madeleine Pennington and my sometimes colleague Ian Christie. It boasts an interesting collection of contributors, including some from indigenous perspectives.

The whole thing runs to 111 pages, at least in pdf, and I’m not going to note the whole thing here. But let me pick my way lightly through it.

In his piece, Ian Christie reflects on the tired metaphors that get wheeled out to describe the climate crisis. There is the ‘wake up call’, although this particular alarm clock seems completely ineffective. There is the ‘last chance saloon’—in which we may, or may not, be drinking—although this has been used so often about so many things that it is now a completely empty phrase. And then there is the ‘perfect storm’.:

This usually refers to an irresistible confluence of forces making for a disaster. In relation to climate inaction, there are three perfect storms to cope with: an ecological one, a political one and an ethical one, all paralysing in their effects. However, the perfect storm metaphor can also have a positive meaning: there can be a gathering of forces that prompt political, moral and economic breakthrough.

I don’t really have space to do Ian’s contribution justice here, but it’s worth mentioning here the two positive ‘perfect storms’ that might yet make a difference. The first is a storm of moral idealism, exemplied by Greta Thunberg and Extinction Rebellion, and other activist groups across the planet. The second is a storm of ‘political realism’:

First, the costs of climate action are looking ever more attractive when compared with the costs of damage from global heating... Second, the risks of fossil dependence have been hammered home by the Ukraine- Russian war. The crisis has made it suddenly possible to frame climate action and mass switching to renewables in the West as an urgent matter of national and collective energy security.

He concludes (I paraphrase) that we need more moral idealism to ratchet up the pressure on the political realism—to make the political realists more realistic:

(I)n reality system change and action by citizens and communities are closely linked.16 Systems can be changed by governments and corporations when they feel pressure from a critical mass of citizens and coalitions.

Alastair McIntosh is a writer whose books on community and spirituality I feel like I’ve been reading all my life. He reflects partly on the experience of living in Glasgow while COP26 was in town:

In advance of the conference, I saw waste ground being manicured in our area. Letterboxes were washed. And as I began to draft this reflection, two massive Chinook military helicopters flew low right past my window... You could say that they left a sense that ‘something’s in the air’.

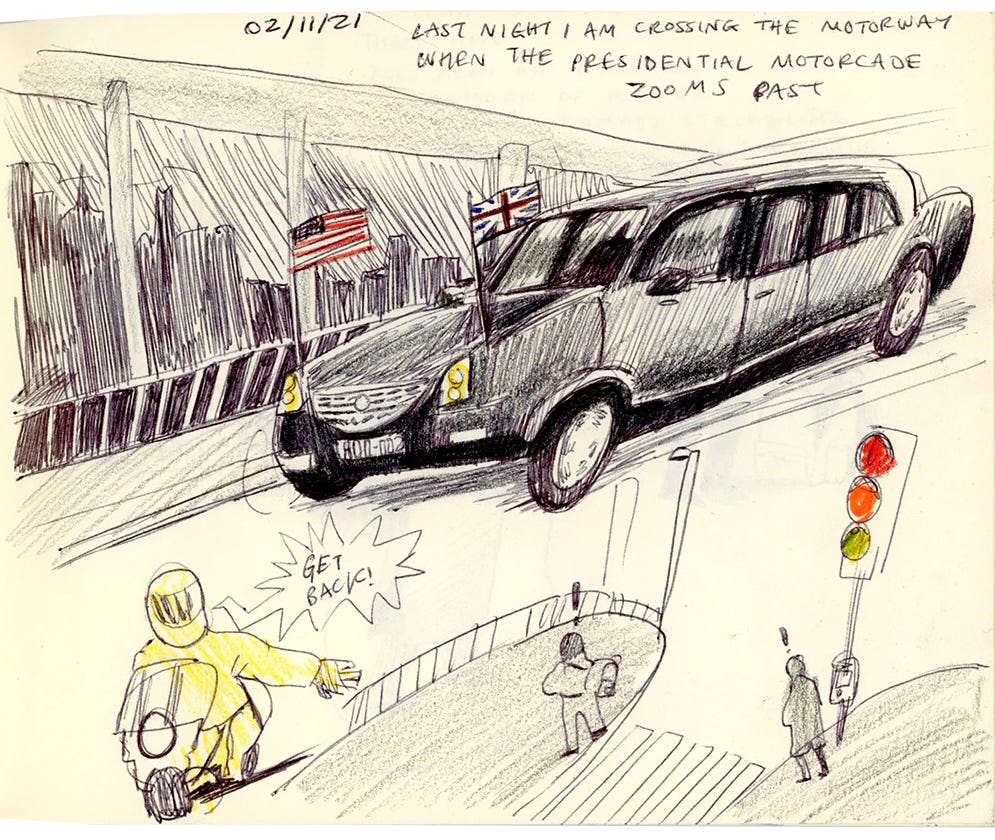

That reminded me of Rebecca Guthrie’s sketch of the Presidential limousine ploughing through the streets of the city, which I mentioned here at the time, and which deserves another outing.

(Illustration: copyright Rebecca Guthrie)

But McIntosh is more interested in what was happening at the edges of the event, where the fringe groups and activists—the ‘moral idealists’, perhaps—were hard at work. He describes this as a ‘ritual space’, while acknowledging that there might be some scepticism:

This sounds like a tall order, and it is. But I’ve noticed that when large events are well held, within a simple framework, people can experience a widening of their worldview. Such events create a cyclical rhythm of departure, initiation and return... In departure, we set out (perhaps unwittingly) on a journey of discovery. Through initiation, we hit the rapids of life, having to face near-crushing challenges – and, whether we succeed or fail, deepening in the heart. Finally, we return to where we started, but this time with new qualities that help us free up the blocked flows of life into our community.

He mentions testimony from those involved in the meetings that bear out his point:

Such openings of inner space, in ways that are anchored to the outer realities of life, are what ritual space can achieve at its best. Ritual unblocks avenues to higher consciousness, to deeper ways of seeing, being, and therefore, to more focussed and hopefully more effective ways of doing.

For me this connected to Maria A. Andrade V.’s essay, drawing on the indigenous traditions in her native Ecuador, about “returning to ancestral wisdom”. Specifically, she writes about four ancestral teachings from the Kichwa peoples, where she comes from:

All four derive from the concept of sumak kawsay, which translates as ‘good living’. The ethic of sumak kawsay nurtures Kichwa’s spirituality, which is reflected in many aspects of their daily life: in their way they up bring their children, in their work at the chakra (their land), in the ancestral use of sacred plants to heal, and in the way they fight to protect the water springs in Pachamama (Mother Earth).

The first is “relationality”, which is a common perspective among indigenous peoples, but not so much among the West:

If the modern world is founded on rationality (‘I think, therefore, I exist’), the Kichwa world is founded on relationality (‘I relate, therefore I exist’). In that sense, individuals are not conceived as beings outside of relationships.

The second teaching is about “common good”: an individual cannot enjoy a ‘good life’ unless their community enjoys it. (Oddly this seemed to resonate for me with some of Jason Stockwood’s reflections on Grimsby that I wrote about here yesterday). The third—connected to the first two—is about ‘good enough’ rather than ‘best’:

This principle has allowed indigenous communities to coexist with nature without destroying it, because, if they only take what they need, then they do not need to over-exploit, over-produce, over-consume and over-discard.

And the fourth is that nature is both alive and also divine—“because it carries the divine fingerprints of a divine God”. This is a sharp distinction from the Western view of nature as a thing (and a thing to be exploited), which I have written about endlessly here.

Some of the values shifts I see, at least around the edges of the rich global North, seem to me to be pointing back in this direction, if not fast enough or decisively enough.

Madeleine Pennington’s conclusion starts by noting the remarks of Queen Elizabeth to COP that:

It is sometimes observed that what leaders do for their people today is government and politics, but what they do for the people of tomorrow – that is statesmanship.

Certainly climate change is an issue for future generations, but it is also a live and pressing issue for many peoples now. Our leaders seem more short-termist than ever, with the political cycle oscillating to the speed of social media.

But whatever the shortcomings of politics are, we are also ‘stuck’ (as Jonathan Rowson notes in his contribution) and need to become ‘un-stuck’. That is going to take a deeper change, and she argues that this is where theology can help:

a theological outlook invites us – all of us – to a far deeper shift of our desires and perspectives. That is to say, it offers not only political incentives to look forwards, but the assurance that the deepest meaning really does lie beyond what is immediate.

I write this as an atheist, but we do need a deep shift in our understandings of the world if we are going to limit the worst effects of climate change and the Sixth Great Extinction. Theology will certainly help.

2: Businesses may be getting more stupid

You wait for ages for an article about stupidity to come along, and then two arrive more or less at the same time. (This was the last one). I don’t know if this is a trend or whether one has been influenced by the other—although there’s no sign of this.

I’ll keep this short, but Scott Galloway’s piece on ‘Big Stupid’ is blessed by an entertaining 2x2:

(Source: Carlo Cipollini via Scott Galloway)

The five laws of stupid—focussing on the bottom left box—are these:

1. Everyone underestimates the number of stupid individuals among us.

2. The probability that a certain person is stupid is independent of any other characteristic of that person.

3. A stupid person is a person who causes losses to another person while deriving no gain and even possibly incurring losses.

4. Non-stupid people always underestimate the damaging power of stupid individuals.

5. A stupid person is the most dangerous type of person.

But as with Ian Leslie’s earlier piece, Galloway wants to move this conversation beyond individuals to businesses:

Just as we underestimate the number of stupid people, we underestimate the business world’s, and seemingly successful people’s, ability to make stupid decisions that damage themselves and others. Success is literally an intoxicant that makes you more risk aggressive and impairs your peripheral vision to reality and risks.

He runs through a series of business decisions that he thinks are stupid, starting with Apple’s Virtual Reality headset, which they’ve been working on since 2015, and which, incidentally, their former Chief Designer Jonny Ive hated:

Mr. Ive argued: “VR alienated users from other people by cutting them off from the outside world, made users look unfashionable and lacked practical uses.”

He also takes aim at WeWork founder Adam Neumann’s latest venture, FlowCarbon, and the investment business RobinHood (the clue is in the first syllable). Coinbase gets slapped for introducing a staff rating scheme that appears designed to spread internal division and rancour:

Every employee gets a scorecard with a rating from 1-10. Those with lower ratings are deemed to have lower “believability,” which co-workers are expected to factor in when considering whether to listen to them. You can’t make this shit up. An organization is a means of leveraging one of our species’ superpowers: cooperation. This is a tool that encourages anti-cooperation, full stop.

It doesn’t maker it better, but Coinbase copied this from the hedge fund Bridgewater, whose HR nous is notorious:

At Bridgewater, 20% of employees leave within the first year. Employees are seen crying in bathrooms... Coinbase can take solace that they also have a great deal of tears in the bathroom, as the stock is 80% below its initial listing price.

I wasn’t completely joking when I wondered about whether it was a trend. Businesses—and especially their current dominant financialised model— are running up against all sorts of limits at the moment. Increasing stupidity might be another sign of these limits.

j2t#326

If you are enjoying Just Two Things, please do send it on to a friend or colleague.