8 July 2023. Climate | Metaverse

Underestimating the economic and financial risks of climate change // Why architects sold themselves to the idea of the metaverse [#476]

Welcome to Just Two Things, which I try to publish three days a week. Some links may also appear on my blog from time to time. Links to the main articles are in cross-heads as well as the story. A reminder that if you don’t see Just Two Things in your inbox, it might have been routed to your spam filter. Comments are open.

Apologies for the slightly slower publication schedule this week and next — caused by some extra work and some family commitments. The next edition will be on Tuesday. Have a good weekend!

1: Underestimating the economic and financial risks of climate change

Many current financial models used by investors are massively under-estimating climate risk. That is the headline from a report called The Emperor’s New Clothes, from the Institute of Actuaries and Exeter University.

Summarising quickly, it identifies three main challenges:

1. Many climate-scenario models in financial services are significantly underestimating climate risk.

Real-world impacts of climate change, such as the impact of tipping points (both positive and negative, transition and physical-risk related), sea-level rise and involuntary mass migration, are largely excluded from the damage functions of public reference climate-change economic models. Some models implausibly show the hot-house world to be economically positive, whereas others estimate a 65% GDP loss.

2. Carbon budgets may be smaller than anticipated and risks may develop more quickly.

A faster warming planet will drive more severe, acute physical risks, bring forward chronic physical risks, and increase the likelihood of triggering multiple climate tipping points, which collectively act to further accelerate the rate of climate change and the physical risks faced. A significant consequence of this is that carbon budgets may be smaller than those we are working with.

And these two challenges are made worse by the existence of regulatory scenarios. Although they introduce some consistency, they are also likely to be under-estimating risks. This is the third challenge. It has two or three effects. It creates the risk of group think; it leads people to make more benign assumptions about the range of outcomes than is justified by the evidence; and it means that companies don’t ensure that they understand the assumptions and limits of the model that they are referencing.

Given that the report is co-written by the Institute of Actuaries and the Exeter University team, it is a chart-rich environment.

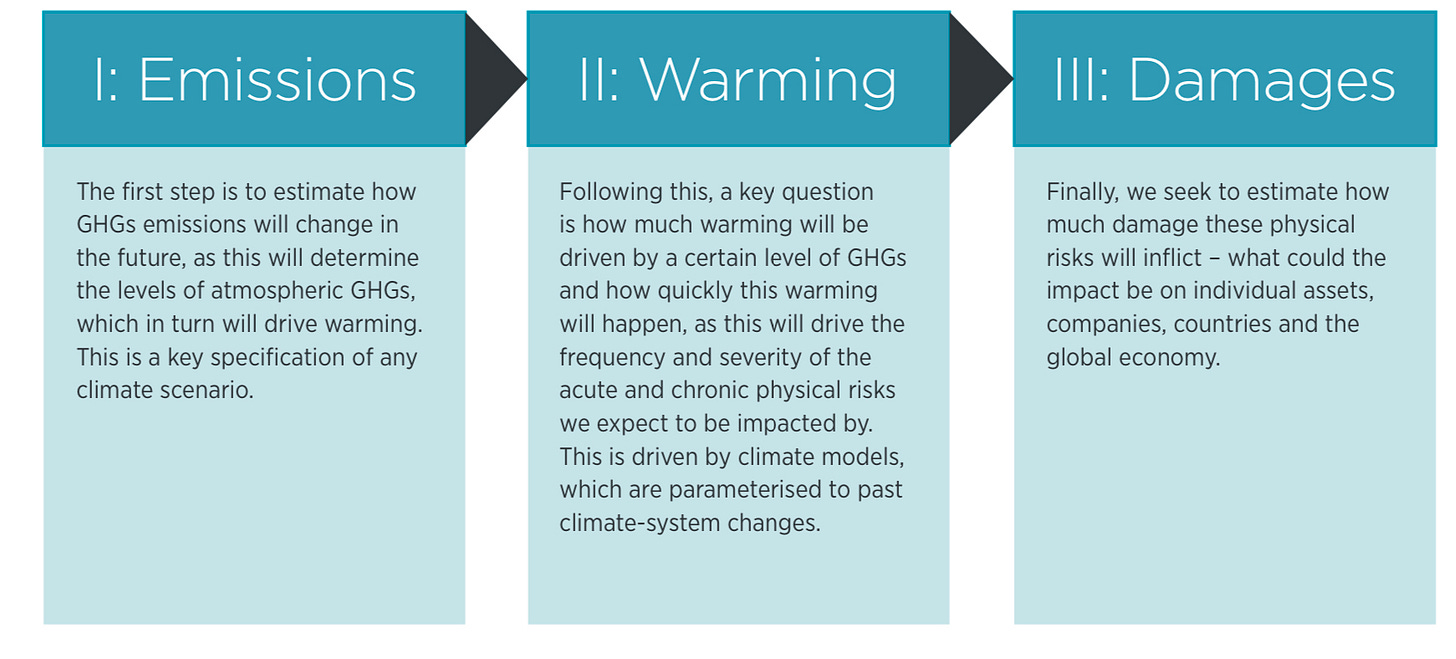

I liked this helpful diagram of how climate models are assembled, for example:

And I also liked this feedback loop between the planet, and the worsening results of warming, and the ways in which society, and finance, can respond. By “double materiality”, it means that climate change is a dynamic problem. The financial system is affected by climate change but it also affects climate change.

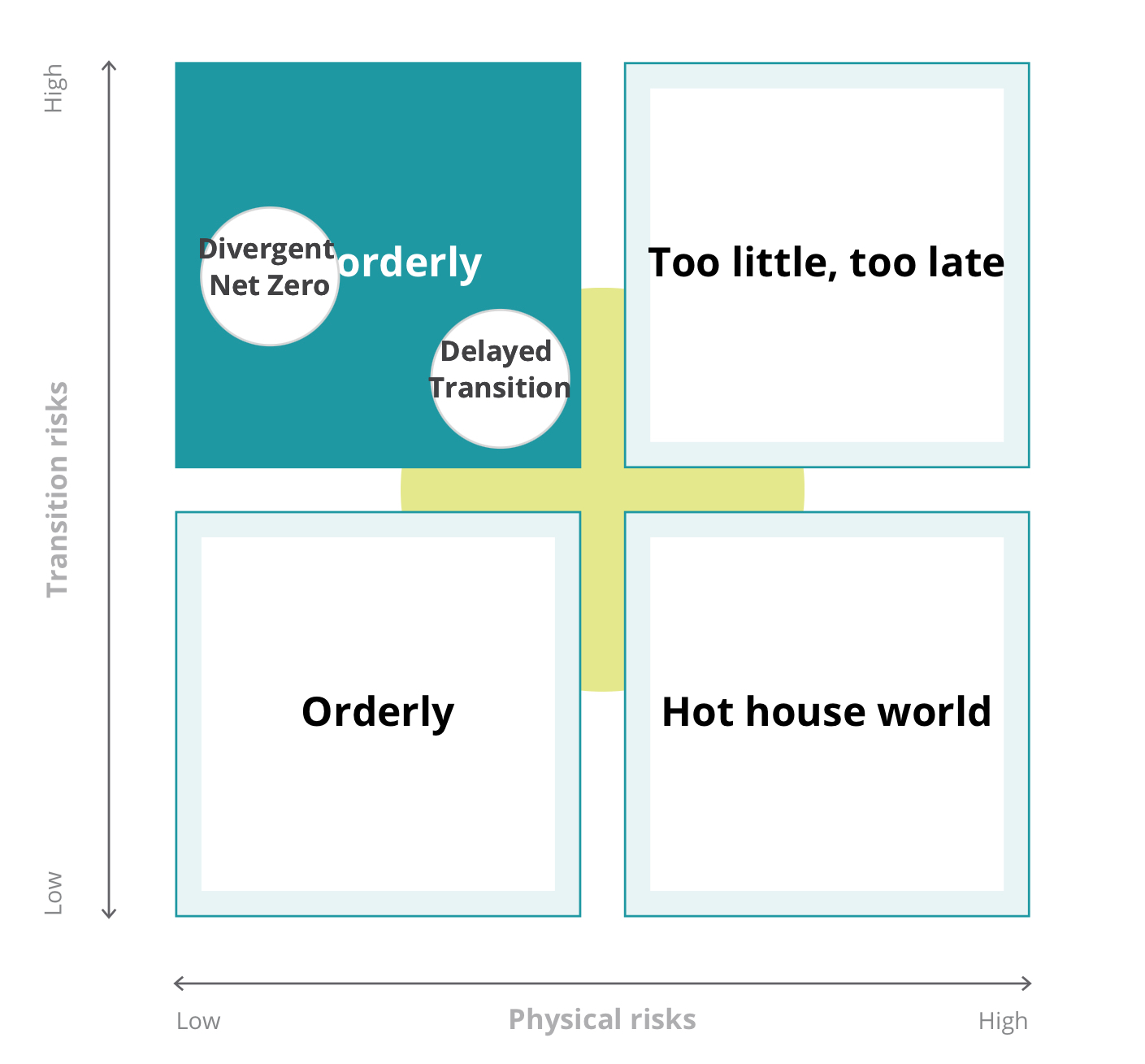

And together these two charts tell an important part of the story here:

Actuaries typically set assumptions in a model using past data. For example, examination of mortality rates enable actuaries to set assumptions for life insurance or pensions. Historic stock market returns allow actuaries to estimate what sort of economic volatility might be experienced in the future. If things change, such as mortality improvements, then actuaries adjust their assumptions accordingly.

However, climate change causes problems for this approach. In the first place, there are a lot of complex interactions inside the climate models:

The level of future emissions in each scenario

How quickly the climate will warm for a given level of

emissions

Whether we cross climate or ecosystem tipping points

The level of damages we will experience as the climate warms, mitigated by adaptation

How quickly we will transition as we react to the physical changes we experience

The pace and scale of the transition in different geographies, economies and sectors

How to incorporate factors such as land use, technological change and nature.

And these are all, pretty much, inter-connected, which means that they potentially generate non-linear risks that are hard to quantify, which may also construct themselves into feedback loops.

But the second, more serious, problem is that the historic data on climate change isn’t very useful. (They use the phrase “limited relevant data”.) I’m always a little suspicious when people use the T-word in reports, but maybe the Titanic metaphor isn’t misplaced here:

(O)ur economy has never been subject to an energy transition of this speed and scale, alongside the increasing physical risk environment we face into. Modelling physical and transition risks based on past data is akin to looking backwards from the deck of the Titanic on the evening of 14 April 1912 and predicting a smooth passage to New York because no icebergs have yet been hit.

The report also critiques some of the climate-based finance reports, and with good reason. In particular some of the GDP estimates under conditions of climate change seem way optimistic.

The NGFS scenarios, developed by the Network of Central Banks and Supervisors for Greening the Financial System—in other words a serious financial group that is trying to ensure that finance takes climate change seriously—has a current policies scenario which leads to 3.2 ̊C of warming by 2100. In the scenario, this reduces global GDP of 18%.

But it doesn’t include

‘impacts related to extreme weather, sea-level rise or wider societal impacts from migration or conflict’,

although it thinks that this will only reduce GDP by another 2%. The scenario also assumes that carbon prices are the only policy lever, and it omits the role of the finance sector in supporting, or not, mitigation pathways.

In contrast, and perhaps more credibly,

Ortec Finance provide a more severe estimate of impacts, citing a negative GDP impact of 73% in the event of a failed transition. Cambridge Econometrics, whose model Ortec Finance use, estimates that a 4 ̊C temperature rise would result in a 65% negative impact to global GDP by 2100.

The authors of the latter report say this is likely to be an underestimate, because it does not account for tipping points in the climate system.

But when you look at some of the assessments by financial sector companies based on three of the four NGFS scenarios (Orderly, Disorderly, and Hothouse), they generally assume trivial reductions in returns compared to the present. Some even assess that the impact on returns of the Hothouse scenario are the same (or better!) than the Orderly scenario. By way of a reminder, in the Hothouse scenario:

Critical temperature thresholds are exceeded, leading to severe physical risks and irreversible impacts like sea-level rise.

(Source: NGFS)

The report suggests that actuaries in particular, and the finance sector in particular, needs to be better informed about how scenarios work—using narrative scenarios as well as models—and there is an appendix to the report with a couple of examples.

It also says that if you’re going to model the financial implications of climate, then you ought to understand climate models better—the implication being that if you haven’t spent the time on this your financial climate-related risk models are going to be terrible. There’s a handy three-box guide on how these models work, introducing a section that explains them more fully.

(Source: ‘The Emperor’s New Climate Scenarios’, IFA/University of Exeter)

The more serious point is that recent financial sector history is fully of examples in which the sector put too much trust in models, which—in hindsight—turned out fo have under-estimated tail risk. Up to and including the global financial crisis.

The authors note that this is because the models ended up being underpinned by assumptions that didn’t reflect what we knew about the real world. The climate models being used by much of the financial sector are like this, only more so.

Why does this matter? Because investors are being told things about climate change impacts that are likely to be materially wrong. This includes public investors like pension funds. And in turn, this means that that are not addressing with sufficient urgency issues about de-carbonising their portfolios, or stranded assets, quite apart from any moral or ethical concerns. As we see over and over again on votes on climate issues at AGMs.

2: Getting the metaverse wrong

I know: everyone’s stopped writing about the metaverse now that it’s clear that it’s not even going to be the next small thing, let alone the next big thing.

Facebook/Meta’s multi-billion bet on the thing seems to have damaged the company’s finances badly, given the number of lay-offs. Sometime in May we learned that Facebook’s total global earnings from its Metaverse project totalled $470, though it’s hard to work out how they would even have invoiced for such trivial amounts.

And one of the features of Silicon Valley culture is that it doesn’t hang round to reflect on its mistakes. The architecture journalist Kate Wagner has a go at this, looking at it through the lens of the architecture profession, in a piece in The Nation called, ‘Lessons From the Catastrophic Failure of the Metaverse’. For the record: I was a metaverse sceptic, partly because I thought it had a business model problem. Though not to the extent of anticipating total global Facebook earnings of less than $500.

(Image: Meta Horizon. Fun, fun, fun. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

But ‘catastrophic failure’ is strong language, so it’s worth going back with her, all the way back to late 2021 or so, and reminding ourselves of the noise at the time:

Last year, some staggering names such as Zaha Hadid Architects, Grimshaw, Farshid Moussavi, and, of course, the Bjarke Ingels Group pledged to create “virtual cities,” virtual “offices,” and equally vague sounding “social spaces” to be funded with cryptocurrency and supplied with art (NFTs)... The rush to move into virtual real estate was a full-on frenzy... with. According to Insider , McKinsey claimed that the Metaverse would bring businesses $5 trillion in value. Citi valued it at no less than $13 trillion.

So one way and another, it didn’t quite go according to expectations:

Far from being worth trillions of dollars, the Metaverse turned out to be worth absolutely bupkus. It’s not even that the platform lagged behind expectations or was slow to become popular. There wasn’t anyone visiting the Metaverse at all.

There’s two stories in her piece. The first is about her home turf of architecture, and its infatuation with doing anything that doesn’t involve designing and building actual buildings.

The second is about the sorts of social spaces that people choose to hang out in when they’re online.

On the first one:

In the social media age, architecture has increasingly gravitated toward PR fluff that doesn’t require making buildings or theory, the two central pillars of architectural production for millennia. While PR has always existed in the field (House Beautiful magazine anyone?) the short attention spans of the content creation era have all but guaranteed that the easiest way to get notoriety in or via a publication is to “create” just that: content (images, renderings, perhaps a 3D city in a program like Blender or Rhino). For added relevance, simply attach this content to whatever the issue—or product—du jour is. Climate change, the pandemic, the Metaverse. I’ve come to call this practice “PRchitecture.”

She wonders if the scale of the embarrassment over the metaverse might be enough to wean architects off this, maybe more in hope than expectation. I’m sceptical, for reasons that she mentions in the article: architecture, for all its nodding in the direction of design and art, is basically a “highly stratified capitalist enterprise”. (Her words).

To which I’d add: and one that is more or less totally dependent on the cycles of capital accumulation and release that govern global property markets.

As Wagner says:

more importantly, the tech industry in its current iteration—which increasingly looks like a never-ending cycle of intangible hype bubbles at its best and financial scams at its worst—is no friend of architecture. It will not provide anything of lasting value or of considerable productiveness to society. The cycles of boom and bust are getting shorter and shorter and the wares being hawked more and more financialized and unstable.

The other point here is about the difficulty that architecture practices seemed to have—when faced with the noise about the metaverse—of imagining how online spaces are used as social spaces. And this is a little odd, since at least in theory architects do worry about the social use of space in the tangible world.

And it’s not as if the idea of virtual worlds is new to architects. As Wagner points out, they use them a lot in their work. And more broadly, we know quite a lot about virtual worlds now:

Virtual social space itself is hardly a new idea—it’s pulled from science fiction and, later, the utopian dawn of the Internet, which imagined it as a kind of boundless, egalitarian, free commons. In our contemporary, monetized version of the net, Zuckerberg does have a point: People want to spend time in virtual spaces and they are important for socialization. Just not his virtual spaces.

Certainly, the metaverse model proposed by Zuckerberg had almost nothing in common with the actual digital spaces where the kids go to hang out. If you ask them:

They’ll say Roblox (the controversial monetized game-design platform), Minecraft (an open world building video game old enough that I played it as a teenager myself), and Fortnite (a player-versus-player combat game with a great deal of customization.) Brands know this; many like Gucci and Nike have begun staging events and product launches in these virtual spaces, trying to capitalize on younger and younger eyeballs.

But architects and architecture haven’t been paying much attention to this. Wagner’s not very kind to architects in her piece, but I still wonder if she’s being too kind. Architecture is a strange business. Most buildings that are designed are never built; the ones that are built are usually changed, sometimes unrecognisably, as the economics of the property market and the constraints of the built environment kick in.

So of course architects are in the attention-seeking business. Of course they chase after bright shiny baubles. Of course they’re ‘show me the money’. Because, as any planner will tell you, many architects (not all, of course) aren’t actually that interested in how people use buildings or use space, physical or virtual.

j2t#476

If you are enjoying Just Two Things, please do send it on to a friend or colleague.