8 February 2022. Solarpunk | ESG

Bringing post-transition cities to life. How to greenwash the financial system.

Welcome to Just Two Things, which I try to publish daily, five days a week. Some links may also appear on my blog from time to time. Links to the main articles are in cross-heads as well as the story. Recent editions are archived and searchable on Wordpress.

1: Bringing post-transition cities to life

China Dialogue has an upbeat piece on solarpunk—a loosely affiliated group of artists who emerged in the late 2000s and who work on developing positive images of a post-transition future.

The article, by Joe Coroneo-Seaman, starts with this extract, taken from The Future We Choose, written by Christiana Figueres and Tom Rivett-Carnac:

“It is 2050. In most places in the world, the air is moist and fresh, even in cities. It feels a lot like walking through a forest, and very likely this is exactly what you are doing. The air is cleaner than it has been since before the Industrial Revolution. We have trees to thank for that. They are everywhere.”

Well, how unlike our actually existing world, where, as Coroneo-Seamna points out, 90% of the world’s population breathe air that is deemed unsafe.

But that’s the point.

At the core of this vision is the idea that humans can coexist in harmony with the rest of nature. A solarpunk world is one where vast swathes of land have been returned to wilderness, rooftop gardens dot the skylines of high-tech cities and vertical farms provide food to their residents.

--

(‘A girl gazes up as a parrot flies overhead in an Art Nouveau-inspired solarpunk city’. Illustration: Rita Fei, via China Dialogue.)

The solarpunk movement started with an informal group of artists using social media to share images of post-transition cities. Since then it’s become a richer form of commentary, and has moved beyond the visual arts:

There are now published collections of solarpunk literature, subgenres of music, movements within architecture and even tabletop role-playing games.

As the field has broadened, so the images of the future have also got richer.

Solar, wind and wave power have entirely replaced fossil fuels as sources of energy, while widespread 3D printing has made it much easier to produce things locally, creating resilient, self-sufficient communities. Increasingly, artists and writers in the solarpunk movement also describe a world that is just and safe for marginalised groups – especially those facing the brunt of the climate and ecological crisis today. “BIPOC (black, indigenous and people of colour) and queer people are safe in solarpunk futures,” says Brianna Castagnozzi, co-editor-in-chief of Solarpunk Magazine.

Obviously this is all in sharp contrast to the bleaker images of cyberpunk, which tend to be far more dystopian, and of course this is deliberate. We all carry images of the future around in our head, whether we want to or not, and so the quality and nature of those images matters. One of the most famous quotes in futures work is from the Dutch futurist Fred Polak, in his book The Image of the Future:

The rise and fall of images of the future precedes or accompanies the rise and fall of cultures. As long as a society's image is positive and flourishing, the flower of culture is in full bloom.

Oscar Wilde also something quotable about maps of the world needing to have utopia on them. So, as the piece concludes,

perhaps it’s time – as Nigerian poet Ben Okri said recently – for artists of all kinds to “dedicate our lives to nothing short of re-dreaming society”.

2: How to greenwash the financial system

I sometimes say that capitalism isn’t working—meaning that it’s not delivering good outcomes for most of us—but it’s more accurate to say that it is working too well. It is being entirely effective at delivering good returns to the owners of capital, regardless of the impact on anything, or everything, else.

That’s the only conclusion you can draw from a long report in Bloomberg on MSCI, the firm that among other things sets ESG (environmental-social-governance) ratings. (Thanks to Rob Miller’s Roblog for the link.)

MSCI delivers indices to Wall Street. ESG ratings are just one of these. But although they’re not regulated in any way, they’re used extensively by investors to validate socially responsible stocks. And theres a second big ‘but’ here as well:

(T)here’s virtually no connection between MSCI’s “better world” marketing and its methodology. That’s because the ratings don’t measure a company’s impact on the Earth and society. In fact, they gauge the opposite: the potential impact of the world on the company and its shareholders. MSCI doesn’t dispute this characterization. It defends its methodology as the most financially relevant for the companies it rates.

The Bloomberg team has done its research. The reporters—Cam Simpson, Akshat Rathi, and Saijel Kishan—went through every ESG rating upgrade that MSCI awarded to companies in the S&P 500 from January 2020 through to June 2021. This included 155 155 S&P 500 companies and their upgrades.

The most striking feature of the system is how rarely a company’s record on climate change seems to get in the way of its climb up the ESG ladder—or even to factor at all.

Here’s how this worked for McDonald’s:

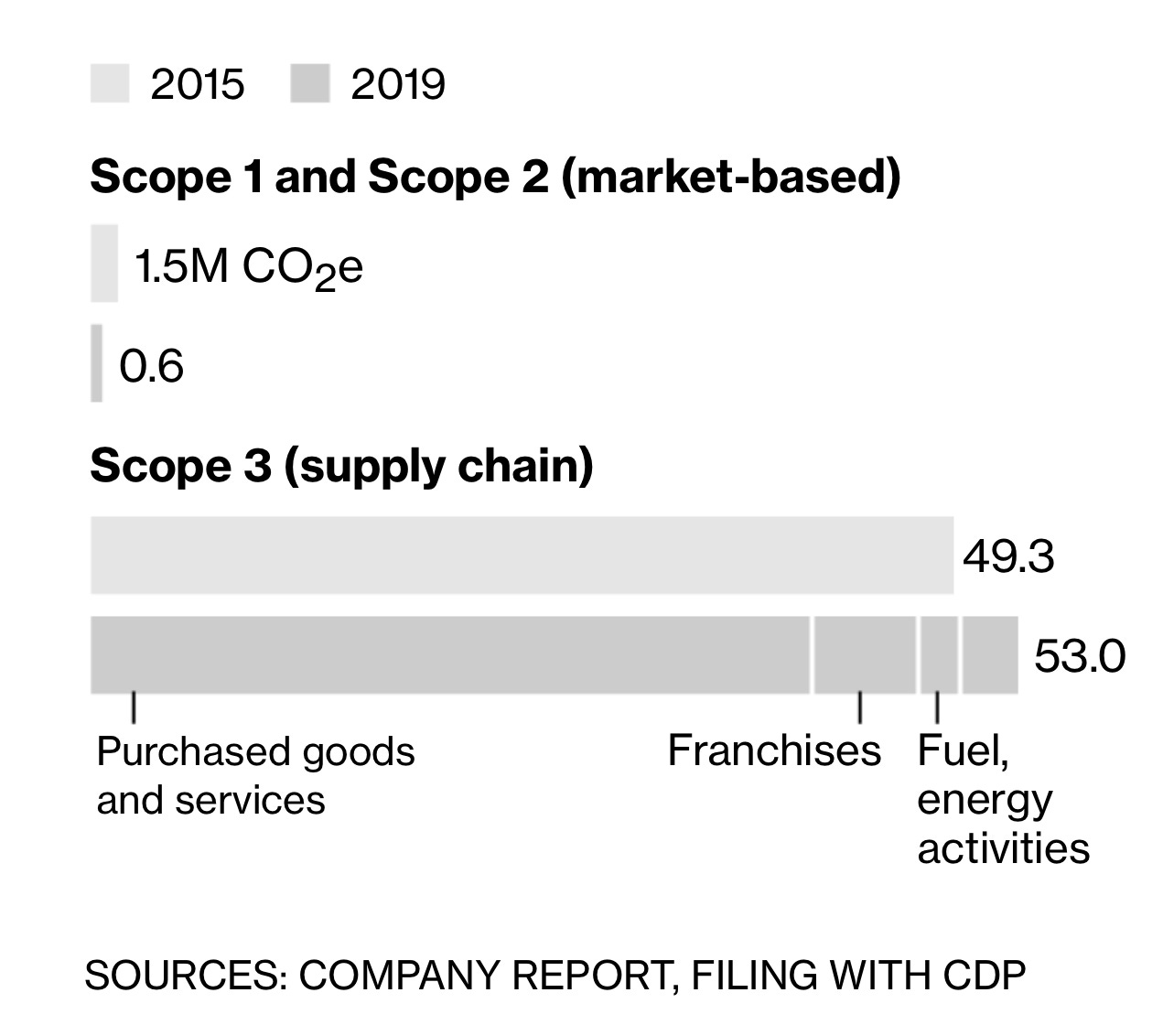

McDonald’s Corp., one of the world’s largest beef purchasers, generated more greenhouse gas emissions in 2019 than Portugal or Hungary, because of the company’s supply chain. McDonald’s produced 54 million tons of emissions that year, an increase of about 7% in four years. Yet on April 23, MSCI gave McDonald’s a ratings upgrade, citing the company’s environmental practices. MSCI did this after dropping carbon emissions from any consideration in the calculation of McDonald’s rating. Why? Because MSCI determined that climate change neither poses a risk nor offers “opportunities” to the company’s bottom line.

—

(Bloomberg: “MSCI’s upgrade of McDonald’s didn’t take into account the company’s greenhouse gas emissions. But they’ve increased steadily.”)

The reporters say this leads to a type of environmental ‘doublespeak’, which is one way of putting it. Another way of thinking about it is as a kind of looking glass world, where the rating a company gets from MSCI isn’t about the impact of the company on the environment—it’s about the impact of the environment on the company:

An upgrade based on a chemical company’s “water stress” score, for example, doesn’t involve measuring the company’s impact on the water supplies of the communities where it makes chemicals. Rather, it measures whether the communities have enough water to sustain their factories. This applies even if MSCI’s analysts find little evidence the company is trying to restrict discharges into local water systems.

There’s a lot more here, and one section is a set of online interactive diagrams that highlight more exactly how some of this works in practice. But almost a third of the upgrades the Bloomberg team assessed were from changes in corporate behaviour that were required by law or regulation, where it would have been operating illegally had it not complied:

In 51 upgrades, MSCI highlighted the adoption of policies involving ethics and corporate behavior—which includes bans on things that are already crimes, such as money laundering and bribery.

It goes on. 71% of the upgrades were for employment or data practices that would be regarded as no more than competent business practice. It also assesses companies against their sectoral peers rather than against good practice generally, so a better than average fossil fuel company can end up with a more positive score.

And it gets worse:

Almost half of the 155 companies that got MSCI upgrades never took the basic step of fully disclosing their greenhouse gas emissions. Only one of the 155 upgrades examined by Businessweek cited an actual cut in emissions as a key factor. As the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development warned in a 2020 report, this means investors who rely on “E” scores and ratings, even high-ranking ones, can unwittingly increase the carbon footprint of their pensions or other investments.

Being in this business has certainly been good for MSCI. Its share price has quadrupled in three years. Although it has competitors in this space, Bloomberg estimates that 60% of ESG investments are made on the back of MSCI data, and that MSCI earns 40% of the revenues in this particular sector.

MSCI’s Chairman and Chief Executive, Henry Fernandez, doesn’t refute any of this when asked about it:

Fernandez concedes ordinary investors piling into such funds have no idea that his ratings, and ESG overall, gauge the risk the world poses to a company, not the other way around. “No, they for sure don’t understand that,” he said in an interview in November on the sidelines of the COP26 climate change summit in Glasgow, Scotland. “I would even say many portfolio managers don’t totally grasp that. Remember, they get paid. They’re fiduciaries, you know. They’re not as concerned about the risk to the world.”

And just one last note here. The article points out that BlackRock has a fund called ESG Aware that “tracks both the S&P 500 and BlackRock’s own top-selling S&P 500 fund”. There are three differences between this fund and the S&P Fund.

First, it has the ESG label thanks to MSCI; second, it’s more heavily weighted in 12 fossil fuel stocks that the S&P 500. And third, BlackRock charges investors in the ESG Aware fund five times as much as the S&P Investors. Unsurprisingly, a former BlackRock executive quoted in the article thinks that “Wall Street is greenwashing the economic system.”

j2t#258

If you are enjoying Just Two Things, please do send it on to a friend or colleague.