8 August 2022. Futures | Uber, again

Mapping the future(s) with Richard Slaughter’s six questions // Uber won’t ever change

Welcome to Just Two Things, which I try to publish daily, five days a week. Some links may also appear on my blog from time to time. Links to the main articles are in cross-heads as well as the story. A reminder that if you don’t see Just Two Things in your inbox, it might have been routed to your spam filter. Comments are open.

1: Mapping the future(s) with Richard Slaughter’s six questions

I was teaching futures at the SOIF Summer Retreat last week, and that sent me back to scanning frameworks, and from there to Richard Slaughter’s 1990s article ‘Mapping the Future’. Of itself, a scan is really no more than a catalogue of the features that you see in the landscape, and most scanning frameworks are fffectively designed to ensure that you fill in your blindspots.

This is obviously better than not filling in your blindspots. But the purpose of a scan is not to build a catalogue: that’s only a necessary condition of success. The purpose of the scan is to help you get to a ‘diagnosis’, in Richard Rumelt’s sense of the word:

A good diagnosis simplifies the complexity by identifying the critical aspects of the situation.

In other words, you are building a systemic and dynamic picture of your futures landscape, in a way that enables you to make decisions about how to act. The reason I went back to Richard Slaughter’s article was because the six questions in ‘Mapping the Future’ allow you to do this:

1. What are the main continuities?

2. What are the major trends?

3. What are the most important change processes?

4. What are the most serious problems?

5. What are the new factors 'in the pipeline'?

6. What are the main sources of inspiration and hope?

Continuities are about the idea that while the futures literature tends to stress change, “some things change very little from era to era... processes of change tend to be limited or conditioned by pre-existing realities.”

Trends—or driving forces, perhaps—are more familiar in the literature: these are substantial forces of change that are changing the landscape, often in combination with each other.

The worked example he gives in the paper includes a mix of major trends, critical issues, and strategies, from a paper called ‘World 2000’ by Halal. I’m not sure that this helps: I’d prefer to work through all six questions, and build the whole map, before getting to critical issues and strategies, which are then informed by the whole discussion that you’ve had to work through the questions.

Change processes might seem, on the face of it, to be the same as ‘trends’, but the way they are described in the paper makes them seem more like ‘inflection points’. These are things where something that has been part of received wisdom, and sits in the dominant worldviews, is starting to crumble. I think the paper could be more rigorous on this, but in the 1990s some of the examples he mentions are (from Lester Thurow’s work) include ‘The end of communism’ and ‘A multi-polar world with no dominant power.

To this Slaughter adds a list called ‘ideas in decline’, about the industrial worldview. For example:

The view that idea is merely a thing or a resource

The idea of progress and unlimited material growth

Serious problems can be understood as issues that are deep-seated and which may prevent other types of change (this is my interpretation of the paper). I’m not sure that the examples in the paper help, but I think of these as being similar to Adam Gordon’s category of ‘blockers’—things that are locked into the system, often with strong reinforcing properties and large vested interests sitting behind them.

In 2022—my examples—I might locate ‘problems’ such as ‘global wealth disparities/ offshore wealth’ or ‘persistent inequality within and between states’ or ‘domination of the tech sector by a small group of large monopolistic businesses’ might come into the category of ‘serious problems’.

In the article, Slaughter talks about the persistence of the ‘industrial mindset’—extractive capitalism, if you like. I suspect that there’s perhaps some overlap between the sub-category of ‘ideas in decline’, above, and ‘serious problems’, but that it might not make much difference in practice.

New factors represent the classic issues that are identified through emerging issues analysis. They’re not necessarily positive or negative. The examples in the paper include:

The human genome project and synthetic organ replacement

The development and applications of nanotechnology

(These examples, from the 1990s paper, also remind us how long it takes emerging issues to emerge.)

Sources of inspiration and hope are essential to agency, and for me, these are similar to the idea of ‘seeds of change’ developed by the Good Anthropocene Project. Here’s their definition of those:

They can be social initiatives, new technologies, economic tools, or social-ecological projects, or organisations, movements or new ways of acting that appear to be contributing to the creation of a future that is just, prosperous, and sustainable.

In the paper, he gives examples that include ‘the notion of a stewardship ethic’ and ‘the re-birth of the sacred’.

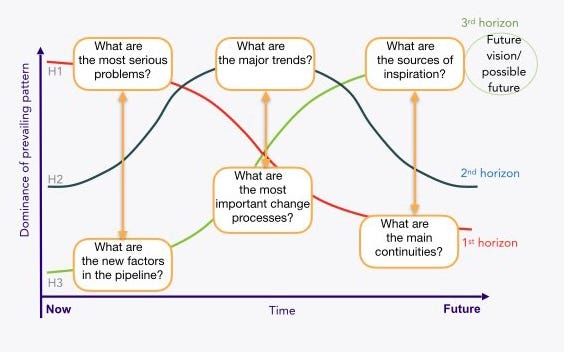

The Three Horizons method hadn’t been developed when Richard Slaughter wrote the paper, but I wondered as I re-read his paper it Three Horizons could be used to map the six questions. It might look something like this.

(Source: Hodgson/Sharpe/Curry, adapted by Andrew Curry)

Even more so, some of the oppositions that seem to emerge from the process might lead themselves to the dilemma resolution approach that Anthony Hodgson evolved from the work of Charles Hampden-Turner.

Dilemmas often fall into the tensions between ‘rock’ qualities and ‘whirlpool’ qualities (yes, we’re talking about The Odyssey in this metaphor). Dilemmas are dilemmas because they have to be integrated—you can’t just choose.

Slaughter has a good example of this type of question in his conclusion:

to what extent, and how quickly, can powerful constituencies (governments, corporations, key decision-makers in all fields and enterprises) bring themselves to set aside the old industrial "game, worldview, etc. and develop a different outlook based on a new or renewed worldview oriented toward new ends; for example, a stewardship ethic; qualitative growth; more caring and inclusive human and economic relationships?

Dilemma resolution connects to Three Horizons, and in Three Horizons terms these are conflicts between ‘maintainers’ (in H1), whose goal is system stability, and ‘visionaries’ (in H3), whose goal is system transformation. We know enough about systems change to know that successful systems transition requires the skills of both—typically through the integrative skills of the ‘entrepreneurs’ who populate H2.

The dilemma resolution method comes with a set of steps that enable the social construction of an integrated outcome that goes beyond the usual organisational trade-offs or compromises when managing change. That sounds like a post for another time. But what I like about the six questions as a scanning tool is that it speaks to the interests and worldviews of all these actors.

2: Uber won’t ever change

I’ve written about Uber from time to time here. But there’s a shocking statistic on The Markup last week. There are so many assaults on ‘rideshare’ drivers that although they represent a tiny proportion of the American workforce, “Uber’s Drivers... comprise nearly 1% of the total number of job-related deaths in the United States.”

Uber confirmed a court document stating that its drivers had endured 24,000 alleged assaults or threats of assault by passengers in the four-year period from 2017 through 2020.

The assaults are probably an under-estimate, since they don’t include assaults by ‘guests’ (individuals who didn’t book the car). The 350 carjackings over the same period are likely also an under-estimate. Oh, and:

The threat of violence in the ride-hail workplace is stark enough on its own. But when you add in the fact that the drivers are not considered employees by Uber or Lyft and don’t receive medical benefits, paid sick leave, or workers’ compensation, an assault becomes even more devastating.

In other Uber news, the company has surprised everyone by announcing that it has turned an operating profit for the first time ever. Apparently, we were right to be surprised: the notion that ‘if a thing seems too good to be true it probably is’ applies to accounting as in other walks of life.

(UBER Eats delivery cyclist in Manchester. Image: Shopblocks/flickr. CC BY 2.0)

The transport analyst Hubert Horan, who has spent more time on forensic analysis of Uber than anyone else, had a long piece posted on the Naked Capitalim site.

One of the problems with trying to interpret Uber’s accounts is that they are designed to be opaque. In particular the company tends to blur revenues and costs from continuing operations and those from businesses that have been discontinued. The second—by Horan’s account—is that Uber has played fast and loose with its EBITDA numbers—“earnings before income, tax, depreciation, and amortisation”.

While EBITDA numbers are a legitimate accounting device, they can be used to dress up accounts, and that’s Horan’s view of what has happened here:

There is nothing wrong with including an EBITDA number in financial reports but misstating it by $8 billion is a different matter. This misstatement allows Uber to mislead gullible investors and journalists into thinking that it is now “Profitable”. Actual EBITDA in the second quaretr of 2022 was negative 3.4%, not the positive 3.6% it has been ballyhooing.

The accounts also show that net margins have improved year on year, from minus 40% to minus 11%. This looks like a big improvement, but unfortunately it’s not possible to work out from the accounts what is going on here:

Uber’s financial reports never included the critical data other large public companies routinely report that would allow outsiders to understand P&L changes. It is impossible to tell whether revenue changes are volume or pricing driven. It is impossible to understand the relative impact of rides and delivery service on profit shifts, or the relative profit performance of Uber’s different geographic markets.

There are good historic reasons for this. As Horan noted, historically Uber was keen not to reveal, pre-pandemic, “how horrible its economics were, and that its extremely rapid growth was not going to produce sustainable profits”. Or during the pandemic, “Uber never wanted its investors, drivers or the cities it served to understand how devasting the demand collapse had been.”

Horan’s best estimate is that the improvement in margin is down to two things. The first is higher prices to ‘rideshare’ customers, (as opposed to customers in the more competitive ‘delivery’ sector); the second is squeezing driver incomes:

Despite extremely tight labor markets, and the fact that drivers are fully aware that Uber customers are paying dramatically higher fares, and face huge pressures to cover skyrocketing fuel costs, Uber actually reduced the driver/restaurant share of total revenue per trip by 6% in the last year. Meanwhile the Uber shareholder portion of revenue per trip increased by 66%.

Given the state of labour markets generally, it’s hard to work out how sustainable this is. (Lyft hasn’t managed to do it.) The other trick seems to be that it has reduced its service areas to the more profitable, more central, urban areas traditionally served by taxis. This comes back to the central problem of Uber’s business model:

In its early years Uber aggressively promoted that its policy of not showing drivers trip destinations would prevent them from avoiding trips to neighborhoods that Yellow Cab drivers had avoided. Uber just announced that it has totally abandoned that policy... Today, Uber offers the same poor service as traditional taxis, but must charge enormously higher fares because of its much higher cost structure.

It’s hard to read the article without thinking that Uber is a ‘zombie’ company. It is propped up by the weight of investor and VC money, which it attracted by telling them a story about digital transformation of a market. But an app does not produce market transformation. The projected returns it claimed actually required it to drive out existing players—in a market that has low barriers to entry and regulatory oversight. But it can’t cut and run because of investor expectations. As Horan says somewhere in this long, long, analysis piece:

perhaps Uber has good reason to downplay, if not conceal the reasons for its recent progress. It is loathe to say anything that might acknowledge the complete dismal failure of its original, longstanding business model.

j2t#356

If you are enjoying Just Two Things, please do send it on to a friend or colleague.