7 October 2023. Development | Power

How to make the SDGs work better // Using the power and interest grid as a mapping tool

Welcome to Just Two Things, which I try to publish three days a week. Some links may also appear on my blog from time to time. Links to the main articles are in cross-heads as well as the story. A reminder that if you don’t see Just Two Things in your inbox, it might have been routed to your spam filter. Comments are open.

1: How to make the SDGs work better

The Chatham House blog has a post by Jon Liden that argues that the United Nations needs to suspend the SDGs (Sustainable Development Goals), at least temporarily, if we are going to achieve the level of transformation we need to meet the challenges we face. They were introduced in 2015 with an aspirational target to achieve them by 2030.

(Disclosure: I work with Chatham House from time to time. Hat-tip to Ian Christie for pointing me to the article).

Liden notes:

The aim was for a world free from extreme poverty, with no hunger, with universal access to affordable healthcare and education, major diseases eliminated, gender equality, climate change and biodiversity addressed, conflicts resolved through international collaboration. And all this was to be achieved within 15 years. We are now a little more than halfway through that timeframe with seven years left.

As everyone probably knows by now, there are 17 targets, one of which is to work in partnership to achieve the other 16. They built on the undoubted success (Liden uses the word “astonishing”) of the earlier Millennium Development Goals:

Coinciding with a period of extraordinary global economic growth, the MDGs, seemed to achieve miracles. Extreme poverty plummeted from 47 per cent of the global population to 14 per cent. Undernourishment fell by half, as did child mortality and the number of children not receiving a primary education... Maternal mortality declined by 34 per cent worldwide. The number of globally reported measles cases declined by 67 per cent thanks to better vaccination coverage.

In contrast, Liden says, the SDGs have not had the same impact:

The UN’s 2023 assessment of roughly 140 out of 169 targets that provided enough data to measure showed that only about 12 per cent were on track; close to half, though showing progress, were moderately or severely off track; and some 30 per cent had either seen no movement or regressed below the 2015 baseline. The UN warned that the world was back at hunger levels not seen since 2005.

Liden suggests that there are two main differences between the Millennium Goals and the SDGs. The first is that the external environment—global economic growth made a big difference. The second is that the MDGs were drawn up by a small technocratic group working with Kofi Annan, then UN General Secretary, whereas the SDGs were developed by a broader and more inclusive process. Hence the list of seventeen goals.

Liden, who runs the Anthropos Institute, argues that right now we have three central global crises: climate change, biodiversity collapse, and food security. These, he says, are exacerbated by our dysfunctional international financial system. Hence his call for a temporary suspension of the SDGs, to focus on these critical issues:

Suspension of the SDGs would allow him to focus the work of countries and the UN on the emergency plans we have in place for climate – the Paris Agreement – and biodiversity – the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework – and on the work necessary to stop the spread of famines and the long-term threat to food production.

It’s a commonplace, of course, that the SDGs are a shopping list of inter-linked issues that make a systemic approach to solving them harder, not easier.

But calling for a suspension would be counter-productive. International agreements to pursue positive change for better and more equal futures are rare and difficult to achieve, and right now there are plenty of bad actors out there who would take political and performative advantage of any step away from the SDGs. Once suspended they’d likely never be re-activated.

For that reason I prefer the approach that Cameron Allen and Shirin Malekour propose in an article in Sustainability Science (outside of the paywall). It’s a long and worthwhile article, which I can’t do justice to here. I noticed after I’d read it that it has been included in the suite of documents that were published in the Global Sustainable Development Report 2023.

They suggest revisiting the SDGs as a set of systems and looking for the leverage points within these systems. As they say in the abstract:

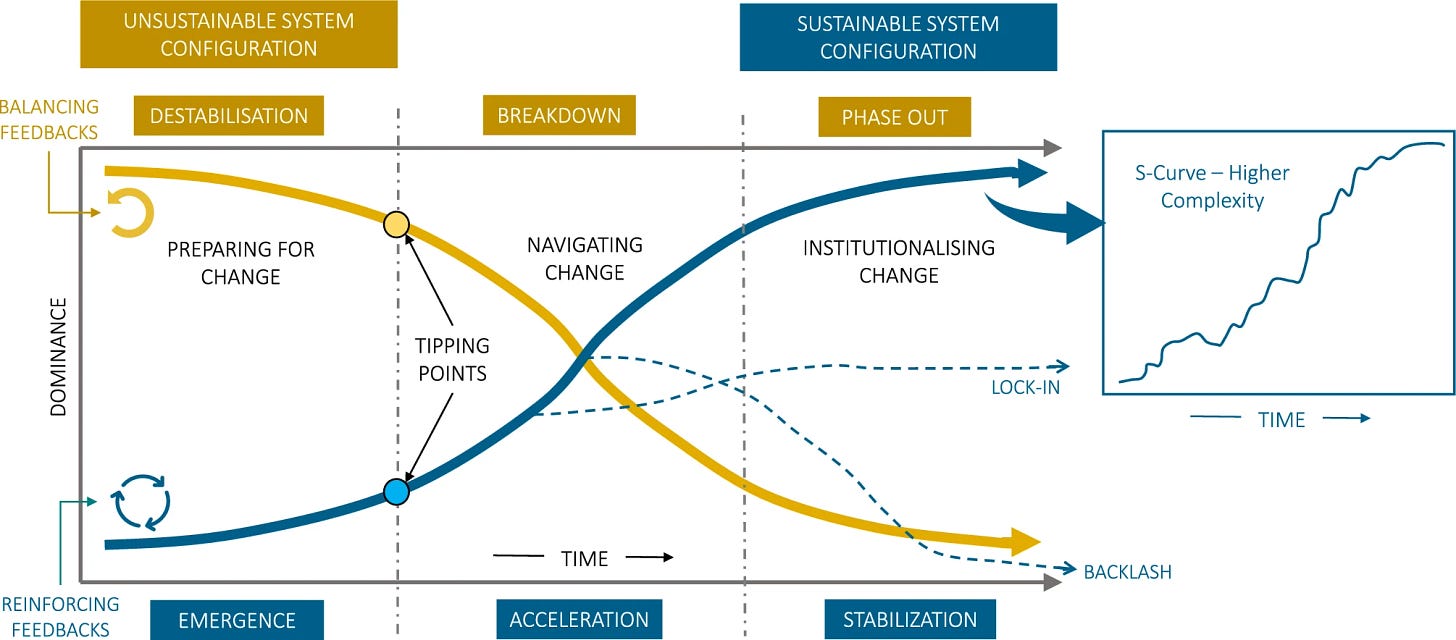

The emerging literature on positive tipping points and deep leverage points identifies opportunities to rewire systems design so that important system feedbacks create the conditions for acceleration... Where resistance is strong, actors can seek to augment system design in ways that weaken balancing feedbacks that stabilise existing system configurations and strengthen reinforcing feedbacks that promote emerging system configurations oriented towards the SDGs.

Reading the article, it’s clear that they haven’t come across Three Horizons as a model of system change, but the schematic they use to explain this transition looks very like a Three Horizons diagram—it’s just lacking an explicit visualisation of the messy middle of the H2 struggle between the present and future systems.

Source: Allen and Malekpour. “An ideal-type sustainable development transition. Rising and declining S-curves across three phases of transformation. Inertia and non-linear dynamics are shaped by balancing (negative) and reinforcing (positive) feedbacks.”)

All the same, their description of the change process spells out the obstructive way that bad actors behave whenever they can—‘H2 minus’ behaviour, as Three Horizons would describe it:

(P)romising emerging innovations can be met with a range of impediments..., resulting in pathways that fail to fundamentally alter the status quo, such as ‘lock-in’ or ‘backlash’, among others. For example, such pathways can be seen in countries where carbon prices or mandatory greenhouse gas reduction targets have been legislated to accelerate energy system transitions but then subsequently repealed due to strong lobbying from powerful interests.

Doing no more here than sketching in parts of the argument, there’s also a strong discussion of the way that lock-in works at multiple levels to maintain existing systems even when they are destructive.

Hence their focus in the article on how to identify positive tipping points to accelerate change—similar to the argument made by Simon Sharpe in recent reports and book.

A positive tipping point (TP) is the point when a certain belief, behaviour or technology spreads from a minor tendency to a major practice over a short period of time... An important insight from this literature is that a mix of well-sequenced ‘tipping interventions’ can push a system across TPs and accelerate the shift to a new state.

In turn this connects to Donella Meadows’ work on leverage points, which in turn connects to the importance of positive feedback (reinforcing loops within systems). This helps sharpen the focus on how we are trying to realise the SDGs:

In the context of the SDGs, shifting the overall goals and intent of systems to reorient them towards the SDGs represents an obvious strategic intervention with deep leverage potential... (A)ctors should determine important systems to be transformed (e.g. health, energy and food), envision and localise new system goals aligned to the SDGs, and begin to build momentum towards these new goals. This would include clarifying the existing (implicit or explicit) goals that drive current system performance as well as desirable new system goals aligned with the SDGs and suitable to local contexts.

There’s much more detail here than I can share on how this works, notably on the way different types of feedback—policy, technology, behavioural—have different effects but also interact with each other. I recommend the article. It makes a powerful case for using the SDGs as a framework of desirable goals and then focusing on the system behaviour that can make it happen, in the context of a rich review of the literature on systems change.

2: Using the power and interest grid as an actor mapping tool

I was running a workshop this week, and we’d used Three Horizons to understand what the preferred futures looked like, and therefore what you might need to do to head towards them from the present.

But although I can’t discuss the workshop here, it was a complex international landscape, with a rich array of actors, from multinational organisations to regional organisations to multiple commercial interests and regulators. So we used a version of Eden and Ackerman’s ‘power and interest’ grid to understand what was going on with the actors, and the kinds of things you’d need to have to do to change the landscape.

I’d first used the power and interest grid in this way in the early 2000s, as a way of exploring a set of scenarios that also seemed to have a complex set of relationships between the actors.

The power and interest grid wasn’t actually intended as a method of actor analysis. In Eden and Ackerman’s book Making Strategy—a book I like—it was introduced as a way to structure and therefore simplify stakeholder mapping. At the time (1998), this was an underdeveloped area. Here’s an extract from the book:

In undertaking a stakeholder analysis, it is usual to focus attention upon a large array of actors who have an interest (stake) in the strategic future of the organization, whether or not they have significant power in relation to the organization. Indeed, as we discussed above, stakeholder analysts often make a plea for the specific inclusion of disadvantaged and powerless groups - the analysis being driven by a value-laden, rather than utilitarian, view of the role of stakeholder analysis. In contrast, our own concern with stakeholder analysis has a strictly utilitarian aim of identifying stakeholders who will, or can be persuaded to, support actively the strategic intent of the organization (p120).

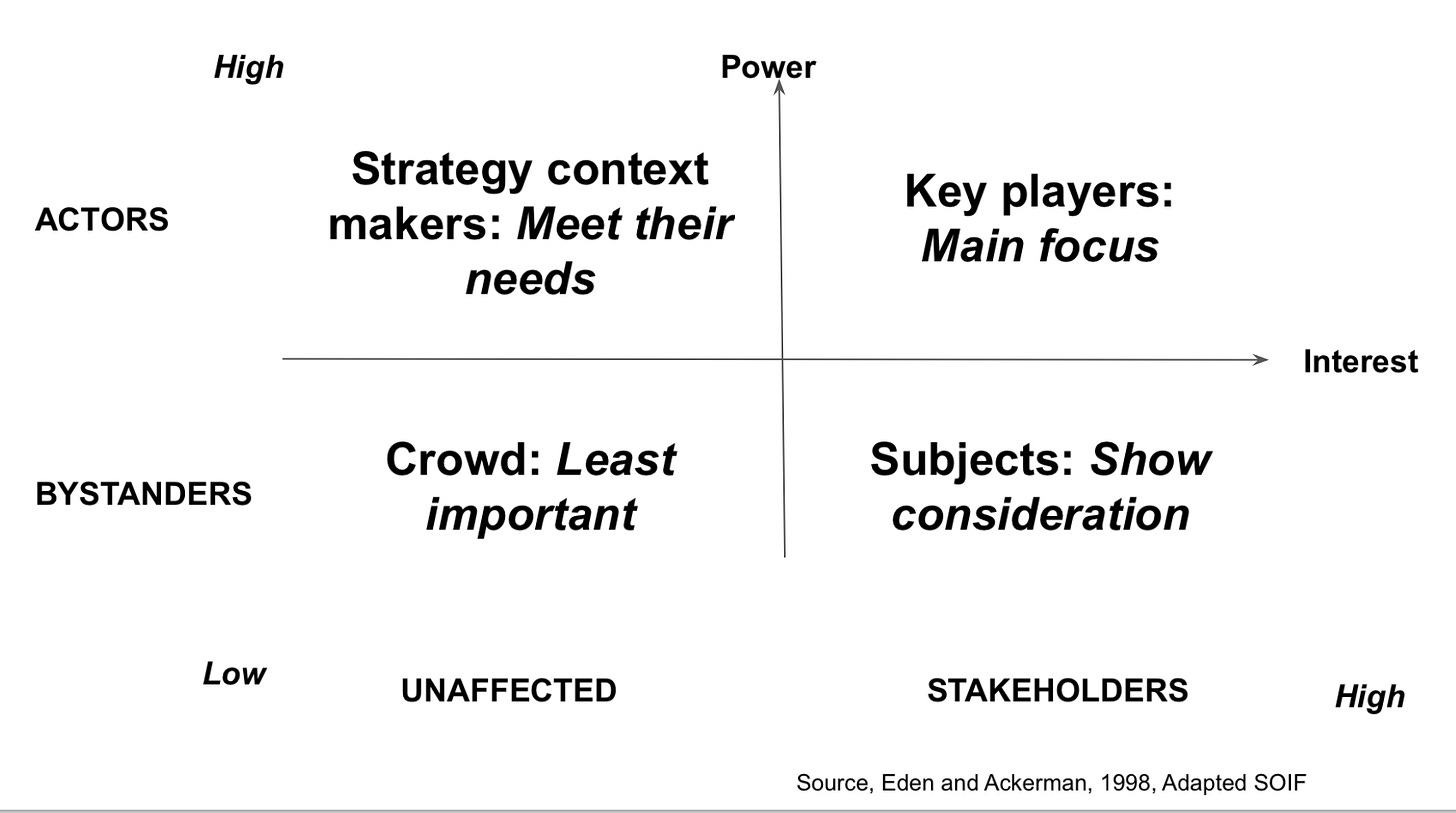

Hence their focus on interest and power. In their version, interest comes first because part of their simplification process is to weed out groups that you don’t need to worry about. And if your interest is in stakeholder management, this leads you to a chart that looks a bit like this. (Although in their version, because they’re only interested in this as a stakeholder mapping matrix, interest is on the vertical axis and power on the horizontal).

(Source: Eden and Ackerman, adapted Curry/SOIF)

But: this is a pretty static picture. You can see it working in partnership with the classic comms RACI matrix, but it doesn’t help you think about actor dynamics. It’s also true that there aren’t many tools in the futures cupboard to help you think about actors. The most detailed one is the MACTOR method, was developed by La prospective, which has been explained by Michel Godet in a couple of places: it’s part of a long and technical paper by Godet in Futures Research Methodolgies V3.0. But, as he says, it takes several months to do it well.

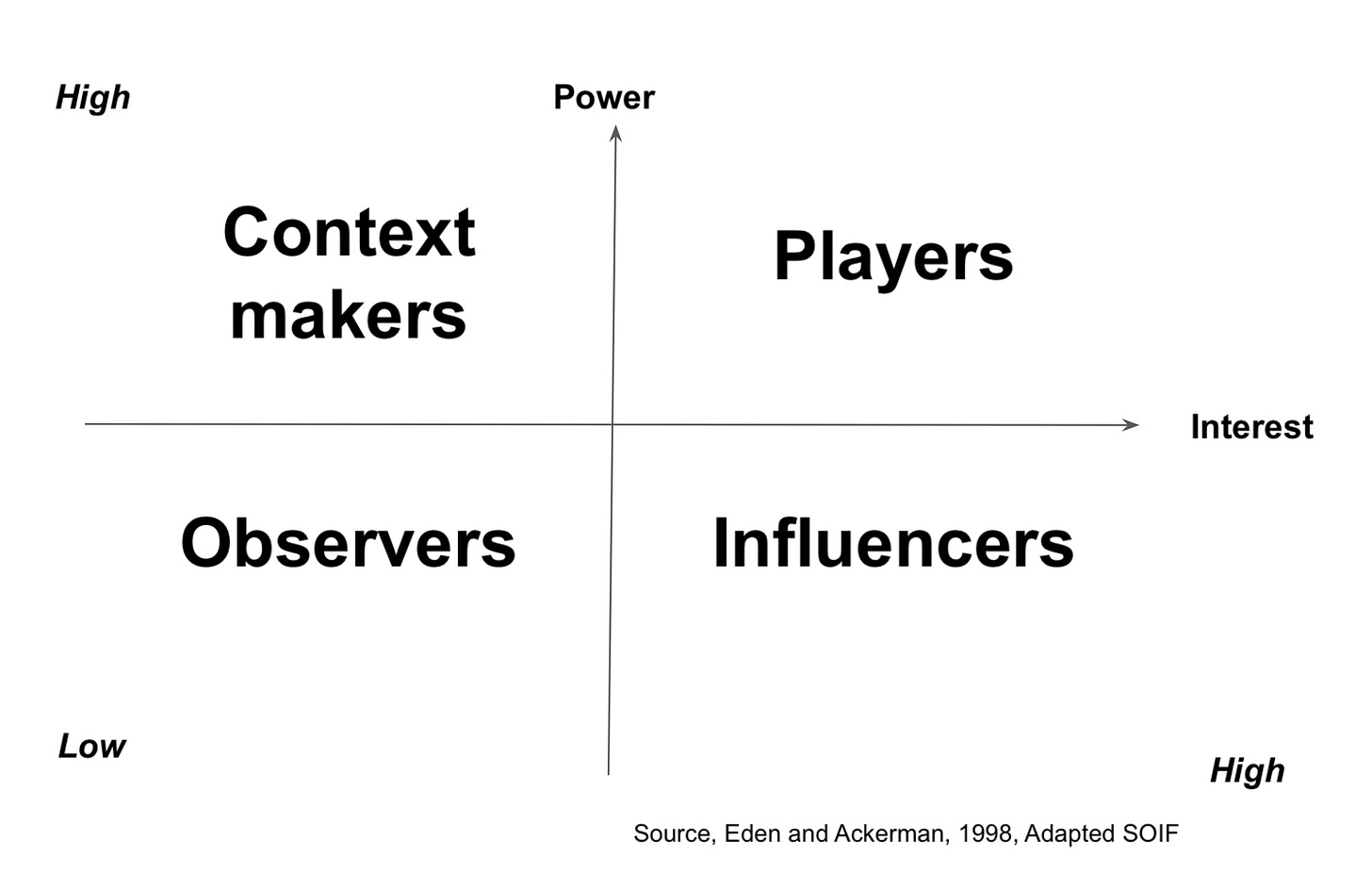

Hence the attraction of adapting Eden and Ackerman’s model as a mapping model as a way of analysing actor interactions in a landscape. The actors still look much the same, but the labels are a bit different.

(Eden and Ackerman, adapted Curry/SOIF)

The Players in the high power/high interest box in the top right are usually fairly easy to work out. The questions here are about financial resources and commitments, political or regulatory authority, about understanding incentives.

Often the Context Makers (high power/low interest) are overlooked, but if you’re trying to change a system, this isn’t about “meeting their needs”. The organisations in this space are typically either financial (in the UK political system, the Treasury is always in this box, which is one of the reasons why the UK system is dysfunctional) or they have responsibility for an overall legal framework of which the system in which you are interested is only a small part. Often the questions here are about rule-setting, and—in terms of change—about re-framing.

Usually the people I work with are in the Influencers box, and in practice they are often both the most interesting and the most dynamic actors in the system, precisely because they are the people who are trying to make change happen. They are—in terms of Molitor’s S-curve—busy “advancing” some new policy ideas.

The questions here are about who is campaigning, and who is lobbying; what kinds of arguments they are using; how those arguments are being framed; what kinds of alliances they are making; and whether they are changing the perceptions of the Observers.

Because: if you can increase the salience of your system to the Observers, the system starts to work in different ways. This is a communications space, largely, about touchpoints, narratives, and mobilisation.

The important thing isn’t just to catalogue the actors on the grid. It is also to map what they are trying to change, and how they are trying to do it. What you’re trying to do is create a dynamic map of the points of change and the strategies being used to achieve it.

When I first used this in the 2000s, the examples that I used were from the world of sustainability in the UK. Looking at this from the point of view of the Influencers, there were different strategies. The World Wildlife Fund was choosing to be an adviser to organisations in the Players space, effectively to get access to the ‘top table’, even as they were accused of greenwashing their partners by other organisations. Some of the influencers built joint campaigns and coalitions, creating—they hoped—enough mass to move themselves up into the Players space.

The RSPB (Royal Society for the Protection of Birds) used mass marketing in the 1990s to build up a membership of several million people, effectively moving Observers into the Influencers space, and it used the money from these members to buy large amounts of land for conservation, although it got criticised for this. But similarly, when it came to conservation issues in the UK, this moved it into the Players’ area.

One more story: A bit later on I met a public infrastructure manager who was trying to refurbish his infrastructure sustainably. He was told (‘Context Making’) that he could only procure this at lowest cost, which meant that it wouldn’t be sustainable. A bit more legal work, and he was advised that ‘lowest cost’ could mean ‘lowest lifetime cost’, at which point the sustainable bids were much more competitive. This is more about ‘changing the rules’ than ‘meeting their needs’.

I have typically used this in public multi-stakeholder projects and ‘futures to policy making’ projects. It works in these. I don’t know yet where it doesn’t work.

Other writing: Bert Jansch

The influential folk singer Bert Jansch would have been 80 this year, and there’s a concert at the Royal Festival Hall at the start of November to mark the occasion. Ahead of the concert, I interviewed Karen Kidson, Jansch’s sister-in-law, who runs the Bert Jansch Foundation, about Jansch and his legacy. The interview has been published in two parts at Salut Live—part 1 here, part 2 here.

Below: Robert Plant and Alison Krause sing Jansch’s song ‘It Don’t Bother Me’. And here’s an extract from the interview:

Q: Obviously Bert had this stellar 1960s, and then he got to the end of Pentangle, and he slips a little out of sight, although he’s still working. But from the mid-1990s onwards he comes back into visibility again. Acoustic Routes gets made in 1992, you see him working with younger artists like Beth Orton. Loren’s influence on that is very visible.

A: Yes, it’s like a third act. My sister (Loren Auerbach) had known Bert since the mid-80s when they recorded together, and they got back in touch in the mid-90s when she performed with him at the 12 Bar Club, and then they married in 1999.

They built his reputation up again through the albums that came out in the mid-to-late ‘90s, and then with The Black Swan. Mick Houghton, his PR, was very helpful in that, and Geoff Travis at Rough Trade suggested people to work with on The Black Swan, people like Devendra Banhart and Noah Georgeson, who produced it. Bert was very open to working with these younger people.

j2t#503

If you are enjoying Just Two Things, please do send it on to a friend or colleague.