7 July 2022. Hip-hop | Culture

Crossing hip-hop with Sri Lankan dance. // What the mediaeval Battle of Crecy tells us about organisational culture.

Welcome to Just Two Things, which I try to publish daily, five days a week. Some links may also appear on my blog from time to time. Links to the main articles are in cross-heads as well as the story.

I’m away for a few days. Publication of Just Two Things will be erratic.

1: Crossing hip-hop with Sri Lankan dance

The Sri Lankan choreographer Usha Jey has been tearing up the internet with a video of her joyful dance Hybrid Bharatham (Episode 5), which combines hip-hop and Sri Lankan Bharatanatyam dance. If you’ve missed it, here it is (1’24”).

An article in Indian Express described it this way:

a stunning mélange as Bharatanatyam adavus (basic steps) hold with popping, locking and breaking effortlessly. Jey, with Mithuja and Janusha (Tamil-Sri Lankan Bharatanatyam dancers from Switzerland), shift personalities with every step as they dance to American rapper Lil Wayne’s 2018 hit, Uproar. “I call it hybrid Bharatanatyam. It is my way of switching between hip-hop and Bharatanatyam, two dance forms that I love, learn, and respect,” says Jey, in an email.

Jey was brought up in Paris, where her Tamil parents moved in the 1990s to escape the quarter of a century long civil war in Sri Lanka.

In a sense the video reflects this upbringing. She grew up with hip-hop in Paris, and only returned to the dance of Sri Lanka—which she describes as her “cultural history”—in her early 20s.

As a child, she’d discovered koothu — an informal dance depicting scenes from ancient epics — through Tamil movies and would perform among family and friends. When she opted to learn Bharatanatyam at 20, she figured it was late, but decided to immerse herself anyway. She found a guru in Bharatanatyam dancer Anthusha Uthayakumar and gave the next few years to the form; hip-hop stayed around.

Her Youtube channel features a series of videos in her ‘Hybrid Bharatanatyam’ series, one of which references the civil war directly (0’50”):

In a previous video she created in her hybrid Bharatanatyam series in 2020, she danced to One Hundred Thousand Flowers, a song about the discrimination and massacre of Tamils in Sri Lanka, created by Canadian-Sri Lankan rapper Shan Vincent de Paul in his album, Made in Jaffna (2021).

Of course, there’s also another story here, about how hip-hop became a global music and a global voice, while also speaking to and for specific cultures. There’s a whole literature there, which I haven’t got time to discuss right now.

But Natalie Brown nods towards it last year in a piece in the Daily Bruin that focused on UK and Senegalese hiphop:

(R)egardless of country or regional specificity, (musicologist Lucas) Avidan said there is a common thread that unites hip-hop together: a progressive youth-oriented voice. This voice encourages listeners and artists alike to take a stock template of youth identity and craft it into their own sounds and concepts, he said.

“Locally, hip-hop is popular because it speaks to a love of culture, but internationally, it has this general (anti-authoritarian stance),” Avidan said. “That’s why (hip-hop) appeals to so many listeners.”

Brown’s article comes with a playlist: ‘Hip-hop around the globe’:

2: What the mediaeval Battle of Crecy tells us about organisational culture

I listened recently to a Tim Harford podcast on what businesses can learn from the French defeat in the Battle of Crecy in 1346. It feels like a bit of a party piece, but there is definitely some substance in there, both in the way that strong cultures can blind us to what’s happening around us, and in particular how they can blind us to technological and social change.

You might not have a good memory of how the Battle of Crecy unfolded, but English schoolchildren of a certain age heard a lot about it. The English were heavily outnumbered but well positioned at the top of a rise, and with a large force of archers, dug in and well protected. A heavy shower just before the French attack softened the ground.

The French knights were regarded at the time as one of the most formidable fighting forces in Europe. They charged repeatedly at the English lines but were decimated every time by the English archers. The French lost thousands of knights, the English around 100 men. You cam see why English schools were fond of teaching it, combining as it does a rich seam of both English self-regard and national prejudice.

Harford is interested in three things: the interaction between individual and group behaviour before the battle; the French of chivalry; and the effect of technological innovation on the latter—in this case the English longbow, and the social relations that went along with it. A Harvard Business Review article on organisational culture gets a look-in along the way, as does the game theorist Thomas Schelling.

The problem of the French armies started before the battle. As they marched towards the English position, the French king Philip gave the order to halt, so they could regroup and rest overnight. But those at the back kept pushing on, and those at the front didn’t want to be overtaken, so they kept pushing on too. Eventually they found themselves, late in the day, milling around within striking distance of the English.

So Philip ordered the attack, sending in his Genoese mercenary crossbowmen first. But the crossbows were wet from the shower, and their defensive shields were at the back with the baggage train. Their arrows fell short of the English positions; the English arrows reached the crossbowmen, and the crossbowmen retreated. (The French knights thought this cowardice).

(The sad fate of the Genoese crossbowmen. From Jean Froissart’s 15th century Chronicles. Public domain).

The French knights therefore attacked, riding over the crossbowmen, in Harford’s account. The English arrows didn’t always pierce the French heavy armour, but they had a lethal effect on their horses. The French chivalric code was that the purpose of battle was to engage the knights of the others side. Retreat was unthinkable. So they charged repeatedly up the muddy slope, through the bodies of people and horses, to less and less effect.

Harford quotes a graphic novel about the battle—who knew there was such a thing—in which one of the English archers says,

'they just don’t get it.’

As he says, the chivalric code didn’t just blind them to better military answers. It stopped them from asking the right questions.

The technology part of this was the development of the longbow, cheaper and lighter and simpler than the crossbow. When it rained, the longbowmen could remove the string and keep it dry under their hats. In battle, they could reload and re-fire more quickly.

But it had taken the English time to build this capability. Edward had forgiven the bowmakers and the fletchers their debts—a big deal in the feudal world—to get the weapons made, and he had, years earlier, ordered every able-bodied man to practice archery for two hours a week after church. He saw his archers—despite their lower social status—as an integral part of his battle plan. This is obviously a sharp contrast to the French attitude to their crossbowmen.

The Harvard Business Review article that is reference is from 2018: “A leader’s guide to corporate culture”.

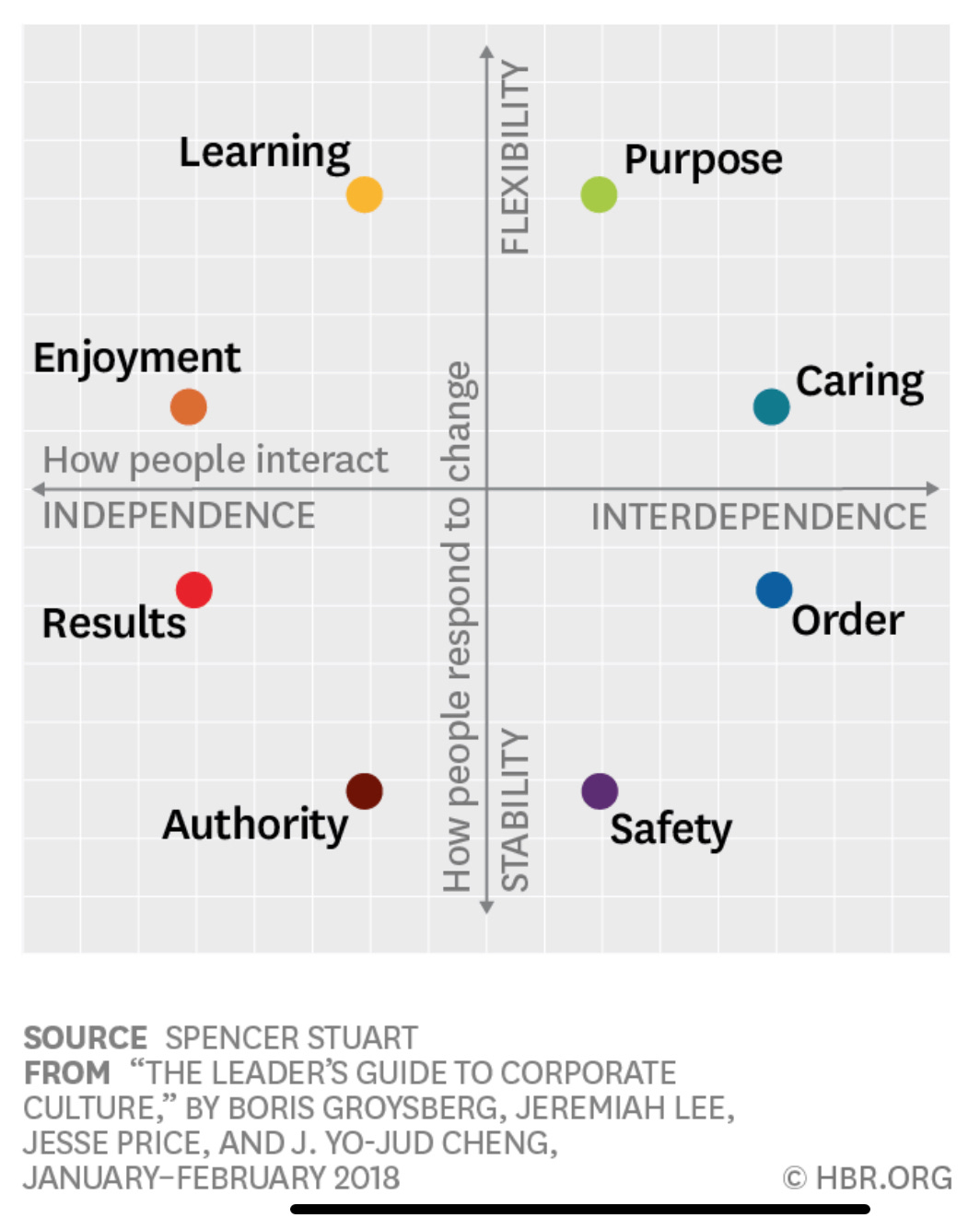

Harford paraphrases it slightly: it includes a 2x2 which frames eight types of organisational culture and 18 references to the word “leader” or “leadership”.

But although none of the eight types capture an organisational culture like that of the French chivalric knights, based on honour, the section that explains what culture is does summarise their problem:

Culture is a group phenomenon... It resides in shared behaviors, values, and assumptions and is most commonly experienced through the norms and expectations of a group—that is, the unwritten rules...

It is manifest in collective behaviors, physical environments, group rituals, visible symbols, stories, and legends...

Culture can direct the thoughts and actions of group members over the long term...

An important and often overlooked aspect of culture is that despite its subliminal nature, people are effectively hardwired to recognize and respond to it instinctively. It acts as a kind of silent language.

The new technology that the English deployed, in other words, completely blindsided the organisational culture of the French knights, and therefore of their approach to the battle. The result was a complete catastrophe in which they repeatedly made poor decisions, and were destroyed as a fighting force.

As the HBR authors say:

Other aspects of culture are unseen, such as... what David Rooke and William Torbert refer to as “action logics” (mental models of how to interpret and respond to the world around you).

But it took this catastrophic defeat for them to recognise this—and the consequences of the defeat lasted for several generations. You can see why Tim Harford thinks there might be lessons here, 650 years on, for organisational leaders.

j2t#343

If you are enjoying Just Two Things, please do send it on to a friend or colleague.