7 August 2023. Ageing | Japan

Florida’s largest retirement community and its economics lessons // Japan is still the future. It’s just not the future we had in mind. [#484]

Welcome to Just Two Things, which I try to publish three days a week. Some links may also appear on my blog from time to time. Links to the main articles are in cross-heads as well as the story. A reminder that if you don’t see Just Two Things in your inbox, it might have been routed to your spam filter. Comments are open.

1: Florida’s largest retirement community has some economics lessons for us. And some life lessons.

There’s a terrific (if extended) piece by Sam Kriss in The Lamp about The Villages in Florida, which is the largest retirement community in the world. Kriss, who is based in the UK, visits it because he has been commissioned to write an article about the place, but he doesn’t want Jason, the sales guy, to know this. So he has a concocted cover story about how his mother is thinking of retiring here because reasons. Jason rumbles him in a heartbeat, but doesn’t care. He thinks that all publicity is good publicity.

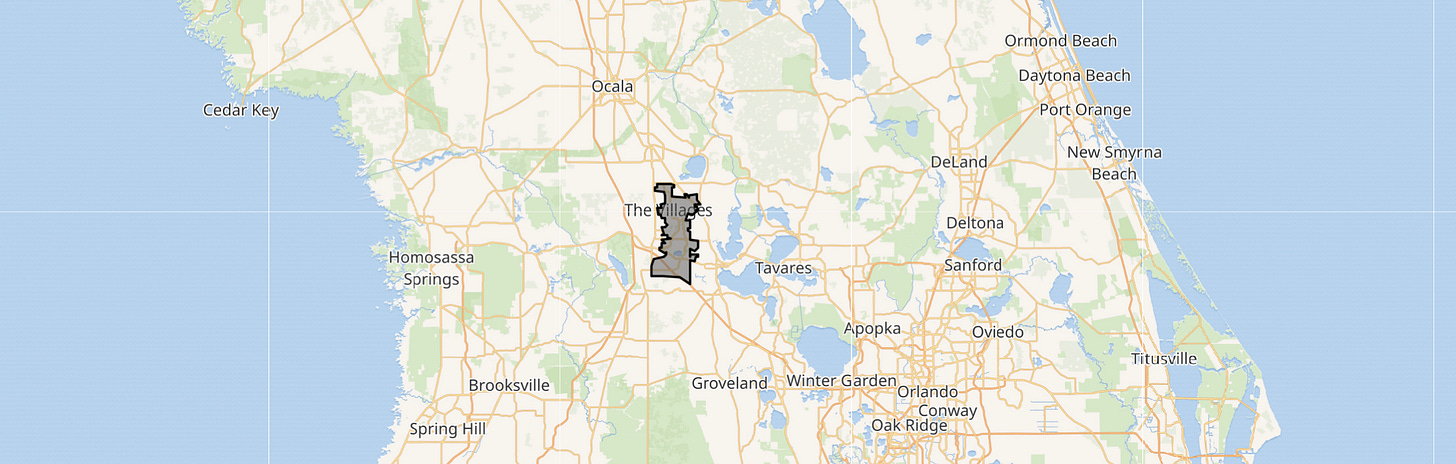

(Sumter Landing in The Villages. Note the golf buggies. Image: Ebyabe, CC BY 2.5, via Wikipedia)

But the reason the piece is terrific is not because it is an entertaining travelogue, but because it also says quite a lot about how things work in an ageing world. My thanks to Ian Christie for the link.

This is how Jason explains The Villages to Sam Kriss. I normally try to keep the quotes from articles shorter than this, but there’s something relentless about the sea of data describing the place. This is not a typical British retirement community in a modern block with some gardens on the edge of a seaside town:

The Villages occupies around eighty square miles of central Florida, which makes it substantially larger than the island of Manhattan. It’s home to some one hundred forty thousand happy, active retired people, with more constantly arriving: this is the single fastest-growing metro area in the entire United States. It contains nine state-of-the-art hospitals, four gun ranges, two one-thousand-seat concert venues, and eight vast churches. It has more than fifty free golf courses, enough for you to play on a different range every week of the year. Ninety swimming pools, not counting the ones in people’s backyards. Twenty of them are Olympic-sized. Something like ten million square feet of commercial space, including a dozen sprawling shopping centers and over one hundred restaurants and bars.

Somewhere that large is going to attract attention, of course. By Kriss’ account, documentary-makers and essayists can’t stay away from the place. As a result there are some well known facts about the place, some of which are untrue:

Everyone knows that The Villages has the highest rate of S.T.D.s in the United States (it doesn’t), that residents attach colored loofahs to their golf carts to signal their wife-swapping preferences (unlikely), and that there’s a vast black market in Viagra (this one’s true)... People treat it like a curio, a weird Floridian quirk, which it is: this city populated exclusively by the retired.

But: even if being in The Villages is a way of removing yourself from the world, you’re still connected to it:

The U.S. has a total G.D.P. of twenty-three trillion dollars, but the assets of all American pension funds are nearly fifty percent larger: thirty-five trillion, a monstrous pile of money accumulated for the sole purpose of allowing Americans to have a nice time when they retire. These pension funds are the biggest players in the financial markets and the biggest investors in every level of the economy.

These two data points aren’t quite comparable. The GDP figure measures the annual output of the American economy, whereas the pension fund assets are a stock that needs to pay out for for years. But the underlying economic effect of this is still noteworthy:

The United States has quietly transitioned into a command economy. Between them, the three biggest asset management firms—Vanguard, BlackRock, and State Street—own almost the entire corporate sector. (They also own an increasingly large chunk of the residential real estate market.) They are strangely unconcerned by the profitability of any individual firm they invest in, since they also own a significant slice of all its competitors. Instead, they’re content to gently guide the entire system of global capitalism towards a maximum general return on investment.

So, disentangling this argument, Kriss is suggesting that in an ageing world, global finance has become a machine for generating future pension payments, and that means that investment decisions in the global economy economy are designed to protect those future pensions:

[M]ass consumer pensions have turned our entire adulthood into a preamble to old age. You work for three, four, five decades—all so you can enjoy those few, brief, useless years between retirement and death. Not just that: everyone in the world is now working to increase the value of your pension... The entire global economy is now a machine for producing satisfied retirees.

It’s a long piece. Kriss meets some of the residents and also some of the service staff. He traces the history of the complex. He hears some accounts of what’s happening in other parts of the world, and other parts of America, that would be filed under ‘disinformation’. People talk to him about the ‘New World Order’, which I have mentioned before here. In fact, he hears a lot of this kind of thing. But this might be a version of ‘the return of the repressed’. As Kriss, notes, The Villages is itself owned by a shadowy and opaque institution, its developer, that sets the rules while being completely unaccountable:

The Villages has no municipal government, no mayor or city council, no town hall, and no police department. It does not even have any meaningful city limits... The Developer effectively runs the three counties on which The Villages sits: most Villagers will vote the way The Developer wants them to. It helps that The Developer also owns the local newspaper, along with the radio station with its constant sunny ads for new housing stock.

(Check in. Don’t leave. Via Google Maps).

People live for longer than they expect, even in America, where life expectancy is lower than in many other parts of the world. If The Villages exists to encourage retirees to spend their money, one of the sad facts about consumerism and ageing is that the money sometimes—often—runs out:

The message of The Villages is this: that the true purpose of human life is to have fun, to drink and play golf, and you can only really experience the true purpose of human life once you’ve retired. ... [But] (t)he most depressing thing I read about The Villages came from someone who’d worked in one of its hospices. By the time the Villagers die, many of them are broke.

2: Japan is still the future. It’s just not the future we had in mind

A few months ago I read a piece by the departing BBC Tokyo correspondent, Ruper Wingfield-Hayes where he took stock of the place. The headline was: “Japan was the future but it's stuck in the past”. I learnt quite a lot about Japan from his piece, but what was meant by the headline was that Japan was once expected to be the next economic powerhouse, challenging the United States. In the 1980s, it was out-competing the US in computing, in electronics, and in more traditional industries such as the auto sector. When I was a financial journalist every airport bookstall was full of anxious books about Japan written by Americans:

America and Europe once feared the Japanese economic juggernaut much the same way they fear China's growing economic might today. But the Japan the world expected never arrived. In the late 1980s, Japanese people were richer than Americans. Now they earn less than Britons.

Yet at the same time, even now:

This is the world's third-largest economy. It's a peaceful, prosperous country with the longest life expectancy in the world, the lowest murder rate, little political conflict, a powerful passport, and the sublime Shinkansen, the world's best high-speed rail network.

(Shinkansen trains ready to go. Image: Rsa, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikipedia.)

So it’s also possible that Japan is still the future—but just not in the way that we imagined four decades ago. Its population is ageing and in decline, and it is not good at absorbing immigrants. Its economy is sluggish.

That’s the starting point for a piece by Dror Poleg, who blogs about cities:

When it comes to social and economic indicators, Japan is further along the curve for many of the trends that will shape the 21st Century: 93% of its residents live in cities , and a large percentage of them are single; The country has the highest percentage of population over 65 , the highest life expectancy at birth , among the world's lowest fertility rates , and many of its young people are virgins or have given up sex altogether ; Japan has the highest government debt per capita ; and is a world leader in using mobile payments (and cash , but not credit cards).

In his piece, Poleg is principally interested in the real estate sector, but even so some of the trends he identifies are perhaps the shape of things to come elsewhere. What’s interesting about Poleg’s list of trends is that they do represent a response to some of the other issues. I’m just going to pick up three here:

1. Alone Together

A growing number of Japanese remain unmarried into their 40s and 50s , and since childbirth outside of marriage is uncommon, the impact on overall fertility is dramatic. The result is a large number of single, childless people living as perpetual renters in large cities. A society of lonely adults in a big, expensive city gave rise to Japanese Share Houses , bringing together adults who wish to share an apartment in order to be part of a community, save money, and have access to better amenities.

(Shared facilities in a Japanese ‘share house’. Photo: Oak House.)

Poleg also notes a trend towards “adult adoptions”—almost all male—where families adopt an adult who will take over a family business and keep the family name alive.

2. Environmental Impact

Japan generates less garbage per capita than any of the large developed countries. It has an elaborate and efficient recycling industry, and its fast food and drink industry relies heavily on PET bottles that allow a reuse rate of close to 90%. Trash cans are often hard to find as people are expected to take their own garbage with them — a great incentive to generate less waste. Beyond large government initiatives, the country is full of smart little tweaks that help save water and paper.

The public transport system, of course, is the best in the world. But the modal share of bikes is also surprisingly high: 14% on Tokyo and 25% in Osaka, according to a recent report.

3. Modular construction

Japan's construction industry is significantly more efficient and productive than the US or the UK. Modular and factory-made components comprise a significant portion of housing construction, and the industry includes a few very large manufacturers that each built millions of houses.

Of course, this makes complete sense in a country with an ageing population and few immigrants, because it reduces labour demand in a sector that traditionally needs young workers.

There’s a similar point elsewhere in a section on the way services are designed:

Once inside the venue, digital sales aides , touch-screen menus , or all-robot staff help make better use of space and reduce operating costs (which leaves a higher margin to be dedicated to rent).

Poleg also talks about the ubiquitous vending machines, but I think they are more a culturally-specific feature of a low crime country. I remember once buying beer from a street vending machine in Tokyo and thinking that it would be destroyed in minutes in London.

In his article, Wingfield-Hayes spends some of his time on what he regards as make-work schemes, such as the compulsory road safety lectures delivered by former traffic cops or the over-staffing of petrol stations. But those apparent inefficiencies seems to have spared Japan—despite a decades-long period of low economic growth—from the extremes of populism seen elsewhere. There’s a reasonable safety net. Japanese companies are likely to have a social purpose, and inequalities of wealth have not increased nearly as quickly as they have elsewhere. Those might also be necessary parts of a stable future in an ageing world.

j2t#484

If you are enjoying Just Two Things, please do send it on to a friend or colleague.