Welcome to Just Two Things, which I try to write daily, five days a week. Some links may also appear on my blog from time to time. Links to the main articles are in cross-heads as well as the story.

A Substack glitch seems to have prevented this being sent out this morning. I’m resending now.

#1: Making sense of plague stories

I’m happy to read pretty much anything by the American historian Jill Lepore, and since she writes for the New Yorker as well as being a history professor I get the chance quite often. She has an essay in the current New Yorker on how plague stories end. (It’s free but tightly metered, which is why I’m running this early in April).

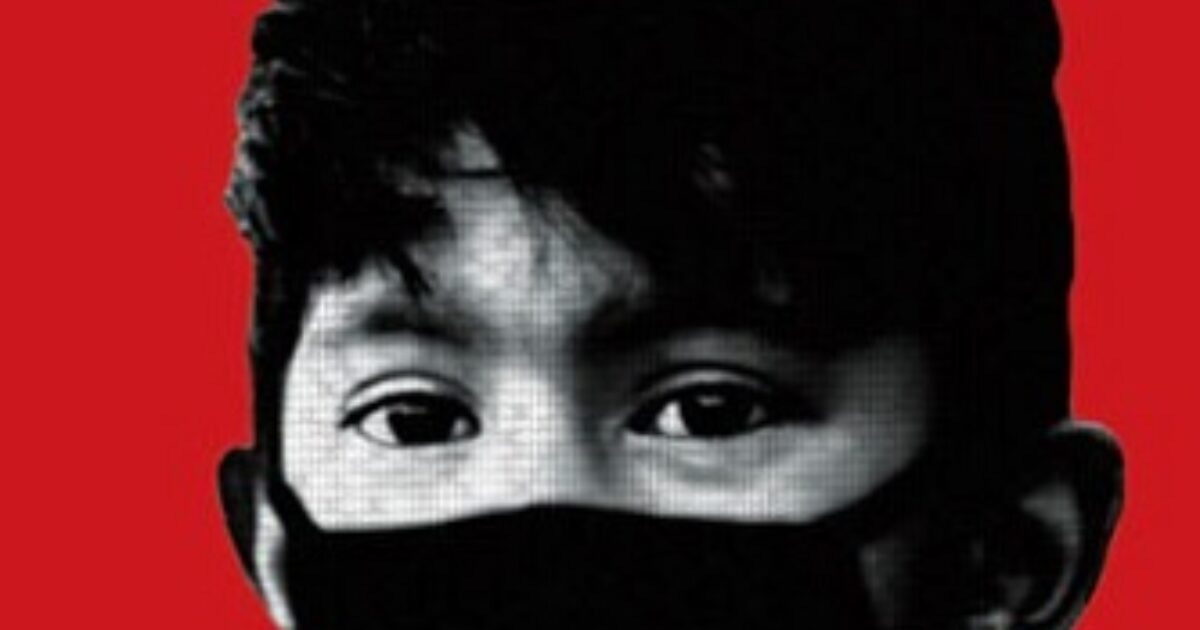

(Image from a poster for Neil Bartlett’s stage adaptation of The Plague)

The usual plot?:

Humans lose their humanity, according to the usual plot. As the pestilence spreads, people grow fearful of one another; families closet themselves in their houses. Stores take in their wares; schoolhouses bolt their doors. The rich flee; the poor sicken. The hospitals fill. The arts wither. Society descends into chaos, government into anarchy.

Sometimes the plague kills everyone, as in Edgar Allen Poe’s 1824 story ‘The Masque of the Red Death’. Sometimes it’s almost everyone, as in Jack London’s ‘The Scarlet Plague’, written just before the Spanish flu and set in 2073 among a handful of survivors.

One very, very old man who, a half century before, had been an English professor at Berkeley predicts good news: “We are increasing rapidly and making ready for a new climb toward civilization.” Still, he isn’t terrifically optimistic, noting, “It will be slow, very slow; we have so far to climb.

A recurring theme is that men and women may die, but books remain. “Some day men will read again”, Jack London’s professor tells his illiterate grandson. In Mary Shelley’s The Last Man the eponymous character sets of by boat, accompanied by volumes of Homer and Shakespeare, confident that he can replenish his stock from the libraries in the ports he visits.

In some plague stories, like those of Jose Saramago, the narrative veil is drawn back to reveal that it wasn’t the plague but politics that was the real problem—a government manipulating the disease to its advantage, and desperate not to be uncovered. (You can fill in your own real-life parallels here yourself).

Some plague stories end better. At the end of Albert Camus’ book The Plague, as the illness recedes, Cottard, the profiteer, goes into the street and starts firing at people, knowing that the game is up:

The narrator of “The Plague” knows what Cottard knew: that the plague pulled back the mask that hides the selfish, ruthless, viciousness of humans. But he also knows something that Cottard did not: that this is not the last mask, that beneath it lies a true face, the face of generosity and kindness, mercy and love.

As Lepore writes—and I’ve tried to select this quote to avoid Camus spoilers here—the narrator explains that he has written his account

to state quite simply what we learn in time of pestilence: that there are more things to admire in men than to despise.”

#2: Making concrete from captured carbon

(Source: Wikipedia)

The Climate 21 podcast featured an interview about the technicalities of “Carbon capture and use” [CCU] with Volker Sick of the Global CO2 Initiative. CCU involves capturing carbon at points of emission (more viable than direct air capture) and then reusing it as a raw material. So CCU can be deployed in the same places as Carbon capture and storage (power stations, for example), but without then having to find a hole to park the carbon in.

The technology allows you to make anything that you might currently be using carbon for—including plastics and concrete—and a lot of the 33-minute conversation turned on the problems and the possibilities of this.

So you can make concrete through CCU, and it turns out to be a better product because it is flexible and doesn’t crack when put under strain. (Fewer potholes, for example).

The problems, inevitably, involve cost. At the moment, said Volcker Sick, making this stuff costs about twice as much as regular concrete. There are different ways of managing this cost difference—a carbon price that represented something close to the actual cost of carbon would make a big difference.

But because the CCU-produced concrete is more flexible than the current regular alternative, it means that it doesn’t have to be repaired or replaced so often. Sick reckoned that once you took the lifetime costs into account, even with current carbon prices, the prices of the two were about even. So you need a customer who is interested in whole-life costs, not just the upfront cost.

He made a wider point that I haven’t heard expressed so clearly before. Carbon emissions are a form of waste, and in other areas of life, we’ve got used to paying for having our waste managed: we pay for sanitation, we pay for refuse to be taken away. Companies are required to pay to dispose of their waste. We either legislate or sanction to make this happen. He thinks it is only a matter of time before we see this same type of waste regime applied to carbon emission waste.

And the cost of this is not that high: “it adds a few cents to the cost of a litre of gasoline.” A few cents! Which begs the question of why we haven’t simply done this already.

The Climate 21 podcast is produced in-house by the business software company SAP, and if I’m honest, my expectations were low. But I learned quite a lot.

j2t#070

If you are enjoying Just Two Things, please do send it on to a friend or colleague.