6 June 2022. Visioning | Libel

Three Horizons and the history of visioning. // Libel, money, and power

Welcome to Just Two Things, which I try to publish daily, five days a week. Some links may also appear on my blog from time to time. Links to the main articles are in cross-heads as well as the story. And a reminder that if you don’t see Just Two Things in your inbox, it might have been sent to your spam filter.

1: Three Horizons and the history of visioning

I recently found a note I’d written—but never written up—about the Three Horizons course I did with Bill Sharpe and Daniel Wahl at Schumacher College in the autumn of 2017. I enrolled because, although I had been involved in developing Three Horizons, I was aware that Bill’s practice of it had evolved, perhaps in different directions, and I wanted to get a better understanding of this.

One of the things I like about Three Horizons is that in mapping a model of change in a single space, it also does two more things.

First, it doesn’t ignore weak signals of change, or emerging issues. These are usually identified in competent scanning, but then get squeezed out of the analysis in the most widely published scenarios methods, in which “important and uncertain” are privileged in the development of the scenarios.

Second, it allows for the creation of preferred visions of the future (normative futures), again in contrast to the dominant scenarios processes, which tend to be more positivist. A bit more than this, as well: it also allows the route towards the vision to be tested in a way that allows steps towards it to be identified.

(If you need to know more about Three Horizons, you can look here or here.)

For me this sits well with Ruth Levitas’ work on “Utopia as method”, when she describes utopian thinking like this:

(I)t allows us, in imagining an entirely different society, to break from the present at least in imagination. This break is not, of course absolute. Our imaginative reach is limited. Both the issues that preoccupy us and our posited transformations in response to them are heavily dependent on our social and historical circumstances.

She also quotes the French sociologist Andre Gorz on utopias:

'it is the function of utopias ... to provide us with the distance from the existing state of affairs which allows us to judge what we are doing in the light of what we could or should do’.

Or heart and hands, if you like. And there’s much more in her paper, linked above.

There’s potentially a whole riff here on whether these dominant North American methods are positivist because that’s a function of American academic culture. After all, their sociology and economics is also more positivist, at least historically, as power relationships are quietly excluded through process, but that’s for another time.

In recovering these elements of preferred futures, it also reclaims the history of visioning which has long been marginalised in all of the noise eclipsed by scenarios methods. Yet, of course, the first modern futures book (Fred Polak’s The Image of the Future) was about the role of visions (images) in shaping the kind of society and the kind of world we want. His book is out of print, but a pdf can be found online.

There’s a famous quote from his book which has adorned a thousand inspirational posters:

(Source: A-Z Quotes)

And Wendy Schultz quotes another passage from Polak’s book in her presentation on visioning at the Tools for Hope site:

These images must have the power to tear our civilization loose from the claws of the present and free it once more to think about and act for the future. The seed of these images becomes the life-blood of our culture, and the transfiguration of our civilization waits upon the sowing of new seed.

There’s more to write on this, but one reason why visioning got eclipsed in futures practice and history may be because it became associated with both the peace movement and community activism through the work respectively of Warren Ziegler and Elise Boulding, and Robert Jungk. (Boulding learnt Dutch to translate Polak’s book into English.)

Scenarios, meanwhile, became associated with military strategy, and later Big Oil, which, as is well known, had access to bigger budgets and readier access to the ears of policy makers, and was also less of a challenge to dominant discourse. Boys and toys.

Ziegler and Boulding focused on ‘a world without weapons’ in their workshops. Robert Jungk developed a community futures method, which he wrote up in his book Futures Workshop, sadly out of print at present. This involved a three-day process that started with a cathartic critique of the things that were wrong with the present, and then moved on during the second day to ask how we would want those things to be reorganised in the future. The third part built the journey from one to the other.

As Jim Dator pointed out in his sympathetic critique of of Jungk’s model, the one thing that’s missing in this is an opportunity to take a view of emerging futures to provide a context for that move from catharsis to hope to action. This gap was brought home to me early in the 2000s when Demos used a different engagement model, Open Space, for a bit of community futuring for the Scottish Highlands town of Nairn. They didn’t have a futures immersion session; at the end of the work, it turned out that what Nairn would really need in 2020 was a fully dualled road to Inverness.

More broadly though, I’m struck that both Robert Jungk’s method, and Future Search, which was developed later, have a dialogue pattern that starts with present discontents, jumps to a better future, and then comes back to agree on what needs to be done to bridge the gap between them.

Written like that, it is the same set of mental models that sit underneath the typical Three Horizons questions, which start with Horizon 1, then move to Horizon 3, and come back to Horizon 2. (Although starting the Horizon 3 and coming back to Horizon 1 also works). I find it reassuring that three different approaches to the same futures problem, which as far as I know were developed independently of one another, have constructed the process in the same way.

2: Libel, money and power

The Johnny Depp vs Amber Heard libel trial in Virginia ended, somewhat bizarrely, with the jury awarding damages to both parties, even if Johnny Depp was the clear winner.

I’m not the best person to write on whether the trial was misogynistic or not—although it seems evident that it was. Don’t take my word for that: Moira Donegan makes this case in The Guardian, as does Chloe Laws in Glamour magazine:

To me, the case has highlighted that a lot of men do not actually care about male victims of abuse, because they are using it to ‘prove’ that feminism is ‘toxic’ and to discredit women who are victims of abuse, rather than showing support or standing up for victims.

What I do want to note is the way that libel laws are used, in both the US and especially the UK as a tool by the powerful to beat the less powerful. Such suits are common enough to have their own acronym: SLAPP—standing for ‘Strategic Lawsuits Against Public Participation’.

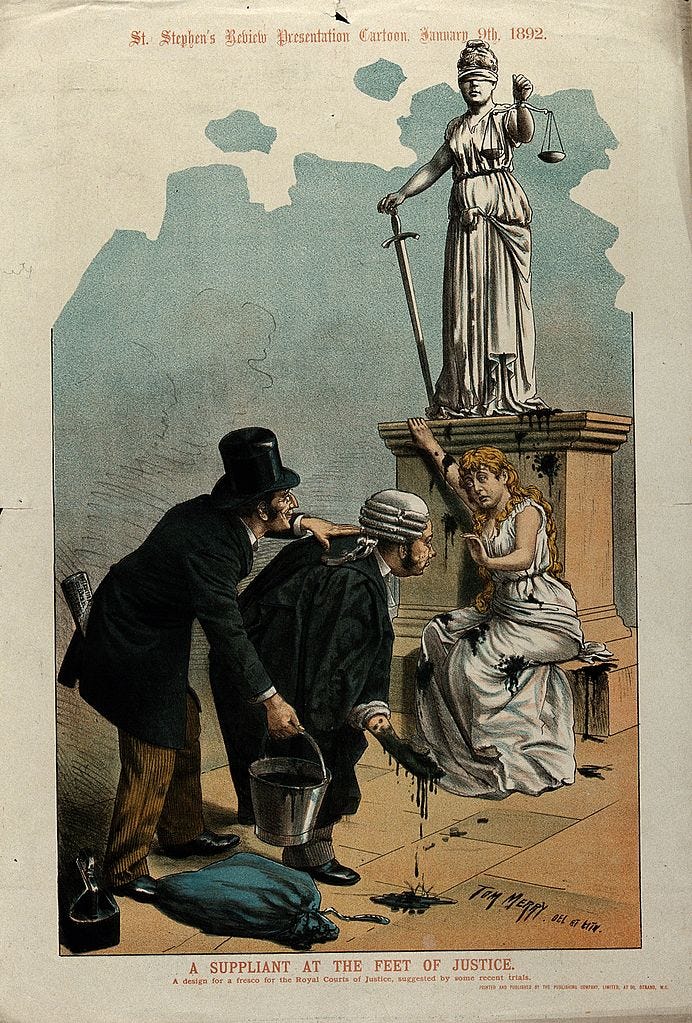

(‘Men throwing black paint at a woman seeking justice’, 1892. Wellcome Collection via Wikipedia.)

Obviously this isn’t just true of gender politics. Catherine Belton was on the receiving end of a similar libel lawsuit by four Russian oligarchs, including Roman Abramovich, over her book Putin’s People. It was settled out of court before it went out to trial, but not before her publishers, Harper Collins, had incurred costs of £1.5 million

And so was Carole Cadwalladr, the journalist who is still awaiting judgment in the libel case brought against her by the businessman Aaron Banks over the nature of his contacts with the Russian government in the run-up to Brexit.

Her twitter thread responding to the Depp-Heard libel case focussed on the relationship between power and the deployment of the libel laws:

I could quote pretty much any part of the carefully written thread, but here are a few extracts:

You have not been sued for libel. So you'll not understand how it's not just designed to silence you. Although it does. But also to destroy you. Which it does too. It's not a pissy business dispute. It's a full-frontal multi-million quid existential assault. On who you are.

It’s a sport, she says, that only the rich get to play, and the impact is deliberately toxic. It’s toxic for the individual who is sued for libel, and it is toxic for institutions that are supposed to articulate the public realm, notably media institutions.

And every step of this process fuels social media:

Cos that's the whole point of it. You won't know how that shit sticks. Even with people you know. You won't know how the rage & unfairness seeps into your bones.

For women, of course, it’s worse, given the rampant misogyny of social media.

As it happens the UK government has held a consultation into SLAPPs, which closed a couple of weeks ago. It described SLAPPs like this:

SLAPPs can be characterised as an abuse of the legal process, where the primary objective is to harass, intimidate and financially and psychologically exhaust one’s opponent via improper means. These actions are typically initiated by reputation management firms and framed as defamation or privacy cases brought by individuals or corporations to evade scrutiny in the public interest.

The Justice Select Committee in the UK is also holding consultation. But this is not just an Anglo-Saxon problem.

SLAPPs are also widespread in the EU. The EU Parliament has also called for reform into their use across the European Union—one of the co-rapporteurs summarised the issue like this:

We cannot stand by and watch as the rule of law is increasingly threatened, and the freedoms of expression, information and association are undermined... Our courts should never be a playground for rich and powerful individuals, companies or politicians, nor should they be overloaded or abused for personal gain.”

Because these cases are rarely about ‘reputation’, whatever the claims that are made in the court papers. They’re about silencing investigation, or environmental activism, or community protest. The murdered Maltese journalist Daphne Caruana Galizia was facing 47 civil and criminal libel suits filed in various jurisdictions when she was killed in 2017; 25 of these were still live in 2020.

Stepping back from the detail, when I worked as a journalist in the 1980s the use of libel suits to silence news coverage did happen—Robert Maxwell was a notable exponent—but was much less common. What’s happened since?

The wealthy have become a lot more wealthy—by at least an order of magnitude—so have far more money to throw at lawsuits.

There is probably more polarisation about what constitutes acceptable behaviour—the equivalent of Amber Heard in the 1980s would not have had the temerity, or the platform, to write an op-ed about sexual violence. And the rise of social media has perhaps both increased the sense of entitlement of the rich and powerful, and the opportunities to make libel claims. (I’m sure there’s a reason why Aaron Banks sued Carole Cadwallader over a TED talk and related tweets, rather than suing the Observer or the New York Times. )

The wealthy have also become more global, and in the process have become a class ‘in themselves’, floating largely detached from the societies in which they operate. As part of this detachment, they have also floated away from social norms about what constitutes acceptable behaviour, as the rise in offshore money indicates. There are lot more rich sociopaths in the Robert Maxwell mould these days. It’s about money; and it’s about power; and it’s about getting away with it.

But perhaps the renewed legislative interest also tells us that we’re approaching—belatedly—some kind of re-assertion of public values and norms.

Updates

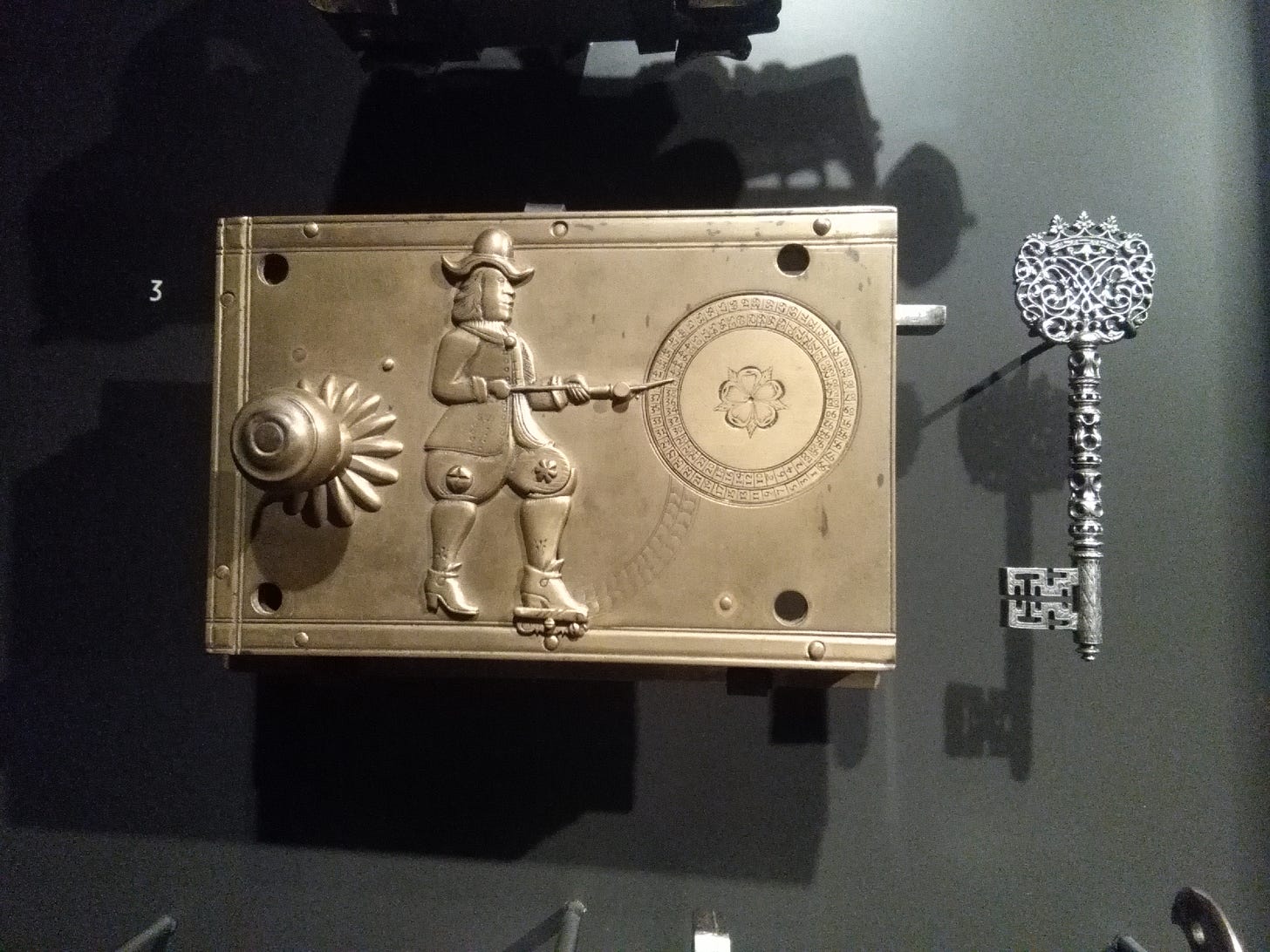

My former colleague Eleanor Cooksey was kind enough to mention the post I wrote here on obsolete objects in a post she published over the weekend featuring some similar ‘obsolete objects’ from the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam.

Let me start with one of my favourites. It’s a detector lock with key... What I liked about the below lock was the ingenuity involved – the keyhole is concealed behind the man’s left leg; with two complete turns of the key, the dial at which the man’s stick is pointing rotates; this records how often the lock has been opened; the doorknob is released when the man’s hat is pushed aside.

—

(Photo: Eleanor Cooksey)

j2t#324

If you are enjoying Just Two Things, please do send it on to a friend or colleague.