6 December 2023. Technology | Architecture

The limits of the machine age. // Buildings are not enough: this year’s Venice Biennale. [#522]

Welcome to Just Two Things, which I try to publish three days a week. Some links may also appear on my blog from time to time. Links to the main articles are in cross-heads as well as the story. A reminder that if you don’t see Just Two Things in your inbox, it might have been routed to your spam filter. Comments are open.

1: The limits of the machine age

Robert Skidelsky is best known as the biographer of John Maynard Keynes, but his most recent book is called The Machine Age. I went to see him talk about the book in London with Nick Spencer, in a live recording for the podcast Reading Our Times.

This piece includes some commentary from a little brochure about the book that includes extracts from the introduction and conclusion, and a flavour of my notes from the conversation, though mostly the former. To give you a sense of the tone, it’s subtitled, ‘An Idea, a History, a Warning’.

The book started out from Keynes’ 1930 essay, ‘Economic possibilities for our grandchildren’, looking out to 2030 and the potential that technology might offer them for more fulfilling lives.

It’s a misunderstood essay, which I have written about here before, but, essentially, he expected that by about now people would need to do a lot less paid work—he thought we might get along fine on three hours a day, or fifteen hours a week. And the reason we’d be able to do this was because of the incremental power of technology:

It turned out that Keynes's prognostication was only partly right. Since 1930 technological progress has lifted average real income per head in rich countries roughly five times from $5,000 to $25,000 (in 1990 dollars), much in line with Keynes's expectation, but average weekly hours of full-time work in these countries have fallen by only about 20 per cent, from about 50 to 40 hours.

Skidelsky suggests that there are three things that Keynes missed in this future projection. The first was the way in which capitalism transmuted needs into wants: mass market advertising was still in its infancy in the late 1920s.

The second is that Keynes saw paid work “purely as a cost… whereas it is both a curse and the condition of a meaningful life.” (Emphasis in original).

Third, he missed questions of distribution and power. Keynes was a liberal optimist, and he assumed that the improvements brought by technology would go to everyone.

The transformational element that Skidelsky brings to this argument is to take it out of the realm of political economy and to take it into the realm of meaning. Specifically, he sees it as a theological argument (and hence his appearance on Reading our Times, run by the theological think-tank Theos.)

There’s a theological reference in the original essay. Keynes writes about this small amount of work being necessary “to satisfy the old Adam in us”. I’ve always skipped past this reference to the book of Genesis, thinking it as just a rhetorical flourish. Skidelsky suggests I was wrong to do this.

The theological reference was explicit: machines would do most of our work for us, making possible a return to Paradise, where ‘neither Adam delved nor Eve span'. Keynes's prediction was rooted in the very old idea that, once the material needs of humanity had been met, a space would be opened up for the good life. Efficiency in production was not good in itself, but the means to the good, and only insofar as it was the means.

In other words, Keynes didn’t assume that people would make the choice of the good life, only that the choice could be open to them.

Marx has a similar view of this possibility. He writes in the German Ideology that communism will free us from the specialisation of labour (even if Leninism had other ideas about this):

nobody has one exclusive sphere of activity but each can become accomplished in any branch he wishes. Society… makes it possible for me to do one thing today and another tomorrow, to hunt in the morning, to fish in the afternoon, rear cattle in the evening, criticize after dinner, just as I have in mind, without ever becoming hunter, fisherman, shepherd or critic.

Marx had a more critical view of the connection between technology and political and economic power, but Keynes seems simply not to have imagined the possibility that the gains from technological innovation would be captured by particular groups within society.

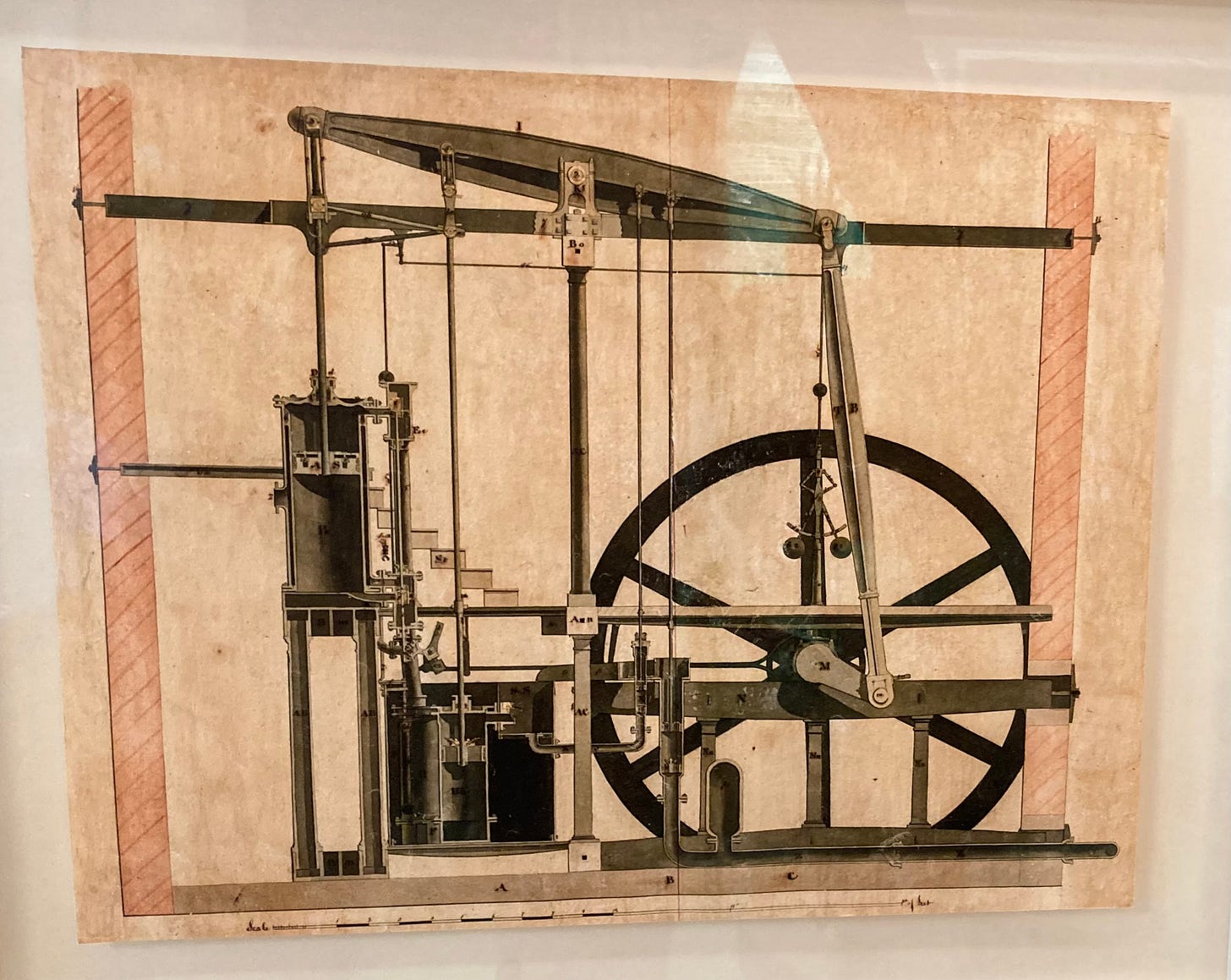

(Early pumping engine, seen at the Royal Society of the Arts. Photo: Andrew Curry CC-BY-SA-NC 4.0).

Thomas Carlyle had declared “the age of machinery” a century earlier, in 1829. He thought it had four components:

a mechanical philosophy, new practical and industrial arts, the systematic division of labour, and impersonal bureaucracy.

In constructing this synthesis, Carlyle also made a distinction between the inhumane and the inhuman, contrasting “the inhumane conditions of pre-industrial life with the inhuman sovereignty of impersonal rules” (my emphasis).

But before this, of course, culture had pointed the way—Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, of course, which Skidelsky does mention, and the work of William Blake, which doesn’t get mentioned, at least in the summary.

Skidelsky sketches out five pathways to the future on the back of our technologies. One is the Keynsian view that they’ll take over the dull work, shared by Toynbee, Lewis Mumford and others, and most recently in the idea of ‘Fully Automated Luxury Capitalism.’

The second is a version of the first one, but with a critical political condition: that capitalism has to be replaced by some other form of political organisation. This might be called the ‘Marx variation’, but it’s also seen in projects like the Lucas Alternative Plan and the work of Mike Cooley.

The third is characterised as “spiritual extinction”. We become our machines, and human freedom is removed. This was a recurring theme in the work of Aldous Huxley; E.M. Forster’s The Machine Stops tells the same story.

(William Blake, ‘Newton’, 1795-1805. Tate Gallery).

Then there is apocalypse, currently having an outing in the discussions about AI. And of course, if The Machine Stops starts in story three, it ends in this one:

Technology is the modern Beast of the Apocalypse. Either it precipitates a disaster—a nuclear or environmental holocaust—or it stops working, leaving humans without a means of livelihood.

The fifth version is captured, says Skidelsky, by Dostoevsky in Notes from Underground. The narrator accuses the technician of wanting

to cure men of their old habits... in accordance with science and good sense. But how do you know, not only that it is possible, but also that it is desirable to reform man in that way. And what leads you to the conclusion that man’s inclinations need reforming?

We’re back with philosophy and culture, in other words. Futurists might notice that these stories almost map on to a version of the scenarios archetypes: growth, discipline, collapse, and transformation. Skidelsky hints that our Dostoevskian escape from this essentially Western worldview might lie in non-Western cultures, but he didn’t touch on that in the interview.

And hanging over the relationship between technology, work and freedom, is a question of paid work, unpaid work that we have to do to maintain ourselves (this work is often gendered) and ‘work’ that we would choose to do if only we had the time. There’s quite a lot of evidence that people can find plenty of worthwhile things to do—if only they didn’t have to go to work.

2: Buildings are not enough

I only noticed this year’s Venice Biennale right at its close, at the end of November, and in truth I don’t tend to get excited about large scale exhibitions like this. But it is clear that this one was different.

The curator, Lesley Lokko, is a Ghanaian-Scottish architect, and the first person of African descent to curate the Biennale, and she had decided that what it really needed to talk about was colonialism and climate change. Half of the exhibitors were African; it was gender-balanced; the average age was lower than it normally is.

This came with its own commentary, in effect. Three of Lokko’s Ghanaian team were denied visas by the Italian government because it claimed they might overstay.

(Lesley Lokko at the Venice Biennale. Photo: Andrea Avezzula. La Biennale di Venezia)

In her exhibition introduction, Lokko describes the Biennale as “the laboratory of the future”.

Aside from the desire to tell a story, questions of production, resources and representation are central to the way an architecture exhibition comes into the world, yet are rarely acknowledged or discussed. From the outset, it was clear that the essential gesture of The Laboratory of the Future would be ‘change’. In those same discussions that sought to justify the exhibition’s existence were difficult and often emotional conversations to do with resources, rights, and risk.

They seem to have been wrestling with the existential question of whether this kind of large scale exhibition can actually change anything. Implicitly, this might be a question about whether the scale and the structure and the prestige and the whole business of national pavilions means that form dictates meaning. In the end, she seems to have concluded that it was possible to tell different stories, to be the change that she’d like to see in architecture:

It is often said that culture is the sum total of the stories we tell ourselves, about ourselves. Whilst it is true, what is missing in the statement is any acknowledgement of who the ‘we’ in question is. In architecture particularly, the dominant voice has historically been a singular, exclusive voice, whose reach and power ignores huge swathes of humanity — financially, creatively, conceptually — as though we have been listening and speaking in one tongue only. The ‘story’ of architecture is therefore incomplete. Not wrong, but incomplete.

Partly to address this issue, the Biennale had a much larger section of ‘Curator’s Special Projects’, which of course gives more scope for new stories. Half of the entries came from small practices, which may also have helped with this project of telling different stories.

Central to all the projects is the primacy and potency of one tool: the imagination. It is impossible to build a better world if one cannot first imagine it... All participants in this Biennale Architettura speak from the richly creative ‘both/and’ position that is specific to those who occupy more than one identity, speak more than one language, or speak from locations long considered outside the centre.

There is a number of reviews online. They seem, consistently, to suggest that Lokko achieved her ambition of creating a different kind of Biennale that opened up different stories and had a different atmosphere from the others.

The Dezeen reviewers, for example, said it was the most global Biennale yet:

A welcome surprise from the Giardini's national pavilions, which have ossified the geopolitics of 19th and 20th century powers, is the presence of indigenous architectural perspectives. This is especially visible in the Nordic and Brazilian pavilions. Nordic pavilion curator, architect and artist Joar Nango, took the commission as an opportunity to platform the Sámi, Europe's last remaining Indigenous population, in a playful and animated anti-exhibition. Children and adults climb over tree trunks and animal hides to explore Girjegumpi, a travelling Sámi architecture library.

(Girjegumpi: The Sámi Architecture Library by Joar Nango and collaborators at the Nordic Countries Pavilion. Photo: Laurian Ghinițoiu (2023). CC BY-SA 4.0)

The Art Newspaper liked the displays that dealt with evidence, and they did sound powerful:

Alison Killing’s architectural investigation of concentration camps in Xinjiang, China, capable of holding 1 million minority inmates at once; Paulo Tavares’s tracing of the ethnically cleansed Indigenous village sites in Brazil in the 1960s; and The Nebelivka Project, Forensic Architecture and David Wengrow’s installation that analyses the archaeological record of a 6,000-year-old Ukrainian city. It builds on Wengrow and David Graeber’s 2021 hit book The Dawn of Everything, to demonstrate that the evolution of human civilisation from hunter-gatherer to farmer to urbanite does not inevitably mean racism, hierarchies, exploitation and autocratic governments.

The review in the RIBA Journal seemed disappointed that there weren’t more buildings on show (architects, eh?):

Also frustrating is a general absence of buildings, although a small sample of African projects hints at a serious effort to develop new languages for architecture whose starting point lies outside the Western canon. David Adjaye presents current work on both sides of the Atlantic – from the national cathedral in his native Ghana to the Newton Enslaved Burial Ground in Barbados – whose design is rooted in local cultures and geography. Niger’s Atelier Masōmī shows its striking public buildings against chalk wall-drawings of vernacular Sahelian architecture.

Lokko had argued at the opening of the event that architects were too interested in buildings and not interested enough in some of the material conditions that surrounded them:

Lokko rejected criticism that the exhibition ‘stops short’ of architecture, saying: ‘The opposite is true; it’s our conventional understanding of architecture that stops short’. The discipline, she argues, is broader than the profession, taking a legitimate interest in all aspects of land use, and in territories defined instead by culture, economics or technology.

The best images, by the way, are threaded through Veronica Simpson’s extended account of the Biennale in Studio International.

j2t#522

If you are enjoying Just Two Things, please do send it on to a friend or colleague.