6 December 2021. Plastics | Work

Forget cleaning up the oceans. Focus on reducing plastic production | Performance based bonus systems are bad for your family And your health.

Welcome to Just Two Things, which I try to publish daily, five days a week. Some links may also appear on my blog from time to time. Links to the main articles are in cross-heads as well as the story.

#1: Forget cleaning up the oceans. Focus on reducing plastic production.

There’s no point in trying to get the plastic out of the oceans, according to pollution scholar Max Liboiron. We should be looking upstream and focussing on reducing plastic stopping new plastics going in. At least, that’s the TL:DR version of an interview with him by Molly Taft in Gizmodo.

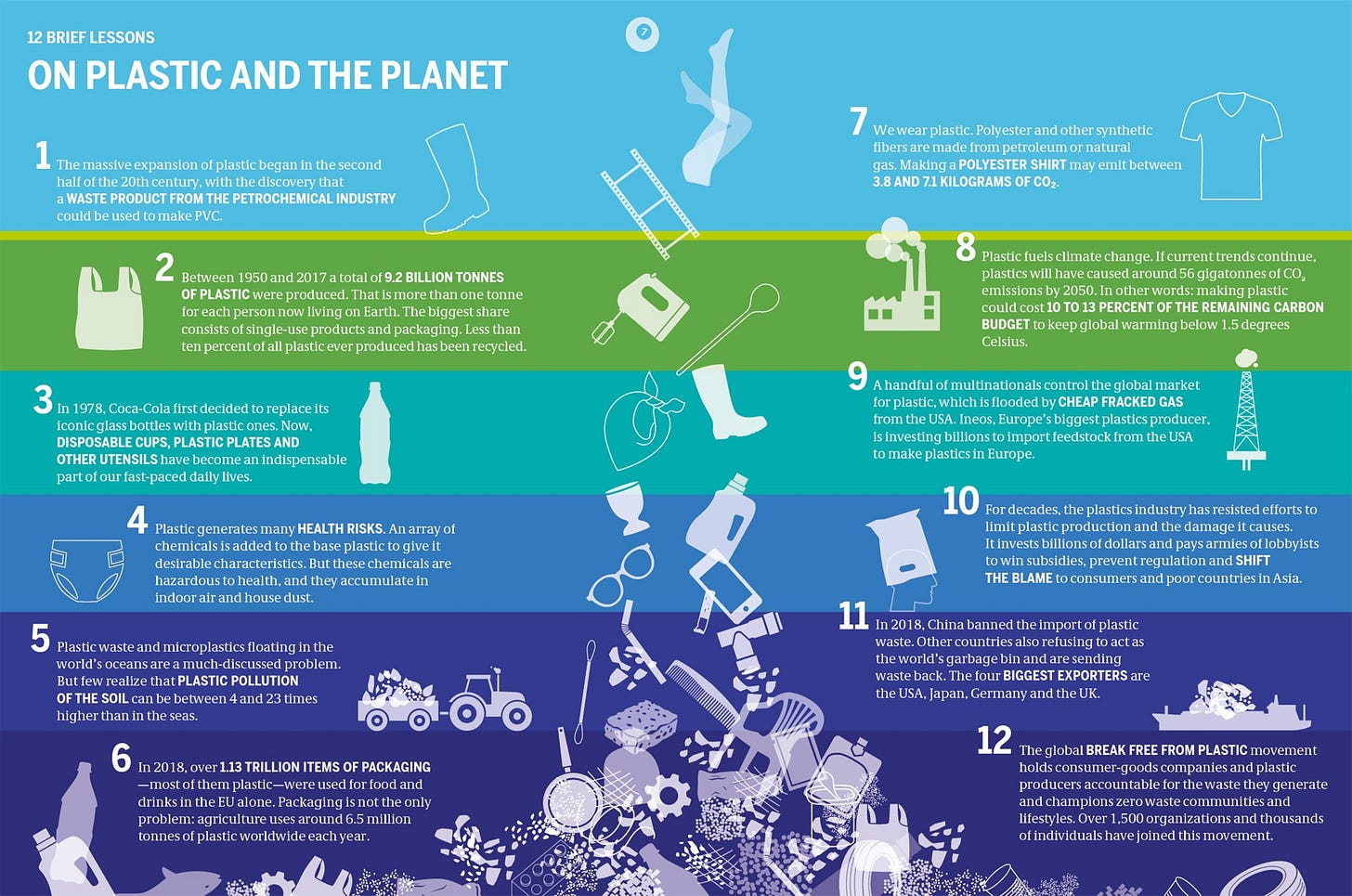

(Plastic Atlas: Poster by Heinrich Boll Stiftung. CC BY 4.0)

Some extracts follow below, but one statistic and one projection help to concentrate the mind: we put eight billion kilogrammes into the ocean every year. Some projections say that on present trends plastic production could triple by 2040.

Max Liboiron: One of the things that’s really important to understand is that cleaning up the oceans is fundamentally different than something like cleaning up litter on the street... You actually have a scale problem where you cannot clean up the ocean in any way at a rate that is commensurate with the amount of plastic going into it. Microplastics are some of the smallest things in the world. They’re smaller than a grain of rice, and they’re in one of the biggest things in the world from a numbers standpoint.

When we teach pollution science, which is different than litter science, what we teach people is that it’s called a stock-and-flow problem. The best metaphor is, OK, you walk into your bathroom and your bathtub is overflowing. Do you, a) turn off the tap, or b) get a mop? I mean, eventually you’ll do both, but you better turn off that tap before you start mopping up.

Taft asks him about the high profile initiative on Youtube that is trying to raise $30m to take 30 million pounds of trash out of the oceans. He says he could find that amount in no time at all in the waters off Newfoundland, where he lives.

He also suggests that although there are very visible examples of sea creatures getting entangled in plastics, quite a lot of plastic goes straight through them, in the same way as bones do, for example.

But although turning off the tap is better than cleaning up, there are some bits of cleaning that are definitely worth doing:

If you want to clean up—and in some places you actually must clean up—there are better and worse ways to clean up. Shoreline clean up? Awesome. Those trash wheels in bays, putting things at the end of sewage outfalls and stormwater drains? Absolutely. Those are great ways to do cleanup. There are many places in the world where those things are essential, because if you have blocked sewer drains and you have a wet season, you’ve got climate change meeting plastic pollution, there’s a clusterfuck. So, yes, cleanup is absolutely essential in a lot of places.

There are a couple of other problems here. One is the plastics exist in a completely different timescale from us—they operate on geological time:

People talk about different eras in time—Paleolithic, Jurassic, etc. They’re talking about species time. Dinosaurs were some of the longest-lasting species around and they died out. It’s not because we’re doomed, right? That’s just how species roll. Plastics last longer than that. Plastics are longer than eras.

(Taft): Yeah, that’s wild.

Liboiron: If you want to get down to the nitty gritty, that includes both polymers, or plastics themselves, but also some of the chemicals that are associated with them. Even if you incinerate plastics, and you end up with some plastic chemicals and slag, those two last longer than species.

The other problem—because of this—is when you do clean them up, what do you do with them?

You can almost never recycle any marine plastics for a number of reasons, including that they’re not terribly recyclable... So even if you get them into a landfill, great, now they’re there for, what, another 400 years to 1,000 years? Fine. And then that landfill will get covered with water with climate change, or just because that’s what happens to planets, and they’ll pop back up again and go back to the ocean. While you shuffle the plastics around, you’ve just deferred the problem.

That’s why turning off the tap is so important.

So what does turning off the tap involve? It involves restricting what corporates can do:

Turn off the tap, turn off the tap. That’s what we do. And we can name who is keeping the tap running. Coca-Cola. ExxonMobil. We have their phone numbers.

The constant and prolific growth of oil has come under threat because of climate change and renewable energy. These monoliths, they’re shifting those efforts into plastics. That’s the good news, actually, because it’s shifted before and it can shift again. We have the playbook and it’s the climate change playbook.

So, once again, this comes back to the power of the petrochemicals industry. Canada, as it happens, is about to end subsidies to oil. In terms of reducing plastic pollution, he says, that’s more important than any form of cleanup.

#2: Performance based bonus systems are bad for your family And your health.

There’s a piece in Harvard Business School’s Working Knowledge series about research on the effects of bonus culture on employee behaviour. In truth, they are pretty much exactly what you’d expect them to be, but the researchers have set out to quantify them.

In short, companies with heavy bonus cultures get employees to prioritise work over family.

The research is by Ashley Whillans, with Julia Hur and Alice Lee-Woon, and here’s the data:

The research shows that workers frequently make decisions about who they choose to spend time with—work colleagues or family—based on how their pay is structured... (E)mployees who received performance incentives spent 2 percent less time each day socializing with friends and family and 3 percent more time with customers and coworkers.

These sound like small numbers, but we spend a lot of time at work. Over the course of a year, that’s eight days more at work rather than with family.

(Photo: The Banker, Cannon Street, London, by Ewan Munro/flickr. CC BY-SA 2.0)

In one experiment, the researchers

presented 545 participants—half paid with incentives and half paid a fixed salary—with choices such as: “Would you go to a happy hour with colleagues or go to your friend’s birthday party?” People who were paid primarily with performance incentives were up to two-thirds more likely to choose spending time with co-workers over family and friends than people paid a straight salary.

Employers who might be thinking that all this sounds just fine might be being a bit short-termist about it.

“Our results suggest that how you start to view the world when you're paid under performance incentives is that any moment you are not working is a moment that's wasted,” says Whillans. “The negative effects of constantly choosing work over personal relationships appear to accumulate over time and in turn contribute to negative mental health outcomes.”

And that tends to come back into the business in the form of sickness, absences, and lower productivity.

One note to add here is that—from memory—other research suggests that bonus systems aren’t an effective way to motivate employees. The buzz of the bonus is short-lived and the amount of money quickly gets internalised and normalised, creating conflict later.

And all bonus systems are endlessly gamed. One company I worked with had managed to construct a system that incentivised people to be more conservative in their outcomes each year, because if they didn’t hit all of their outcomes they didn’t get their bonus.

And as the Working Knowledge article points out there are other forms of incentive—time-based, or non-work benefits—that may work better

The full article is online here.

j2t#221

If you are enjoying Just Two Things, please do send it on to a friend or colleague.