5 September 2023. China | Non-places

The problem with China’s economy. // How super-modernity detaches itself from the world

Welcome to Just Two Things, which I try to publish three days a week. Some links may also appear on my blog from time to time. Links to the main articles are in cross-heads as well as the story. A reminder that if you don’t see Just Two Things in your inbox, it might have been routed to your spam filter. Comments are open.

1: Are China’s economic issues a ‘gear shift’ or a blip?

There’s an emerging consensus that the Chinese economy is slowing fast, and that the techniques that have been used to stimulate it over the past three decades aren’t going to work this time.

Important if true, as they say, and there’s quite a long piece in the Wall Street Journal that spells out the current prevailing view on this. (My thanks to Charles Arthur for the link here, which seems to bypass the WSJ paywall, at least for the moment.)

The model that enabled the Chinese economy to grow as quickly as it did over several decades involved very high savings rates, that were then re-invested in infrastructure. This worked well when the economy needed more capital investment to grow, and was similar to the model that both Japan and South Korea used to develop their economies.

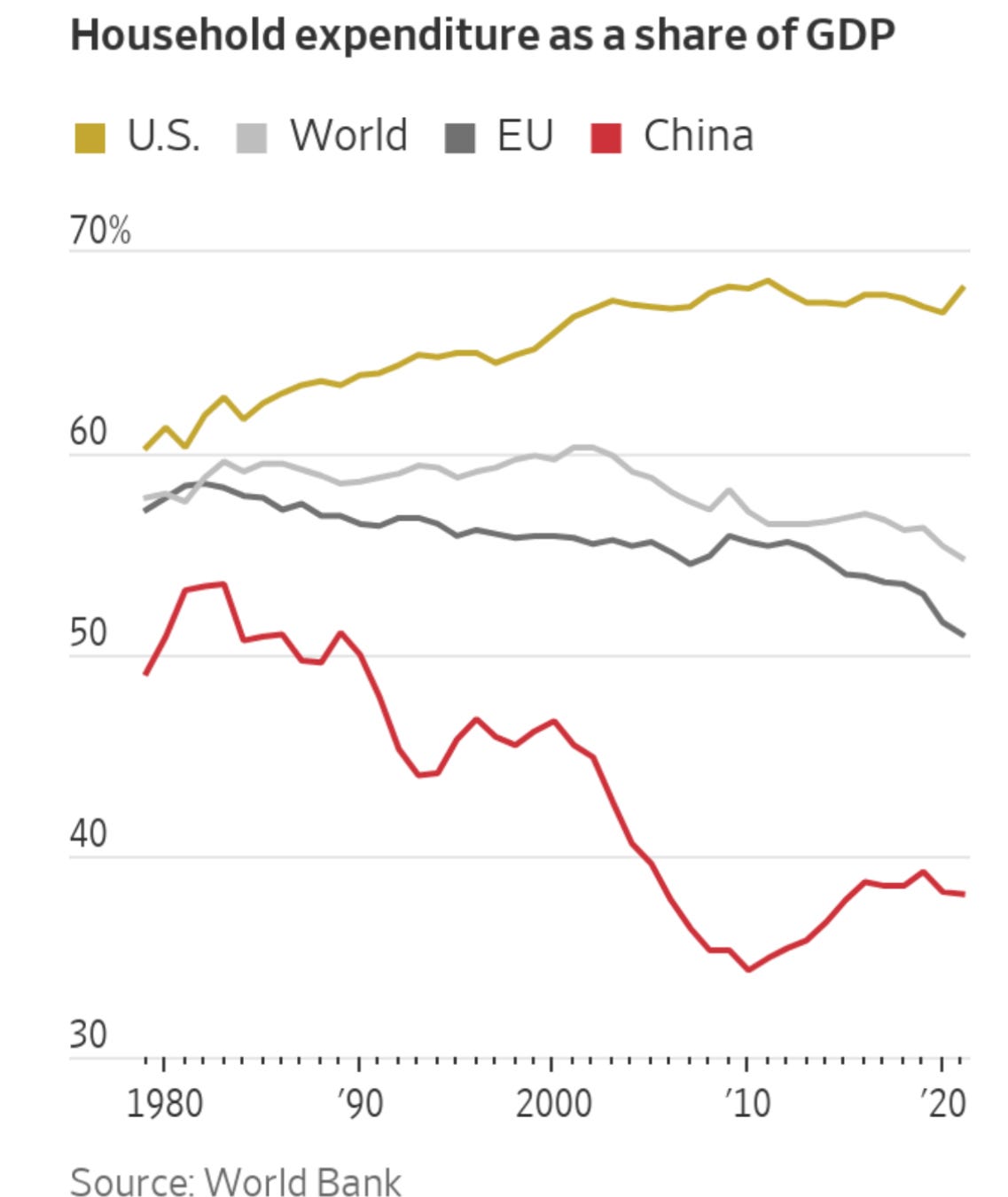

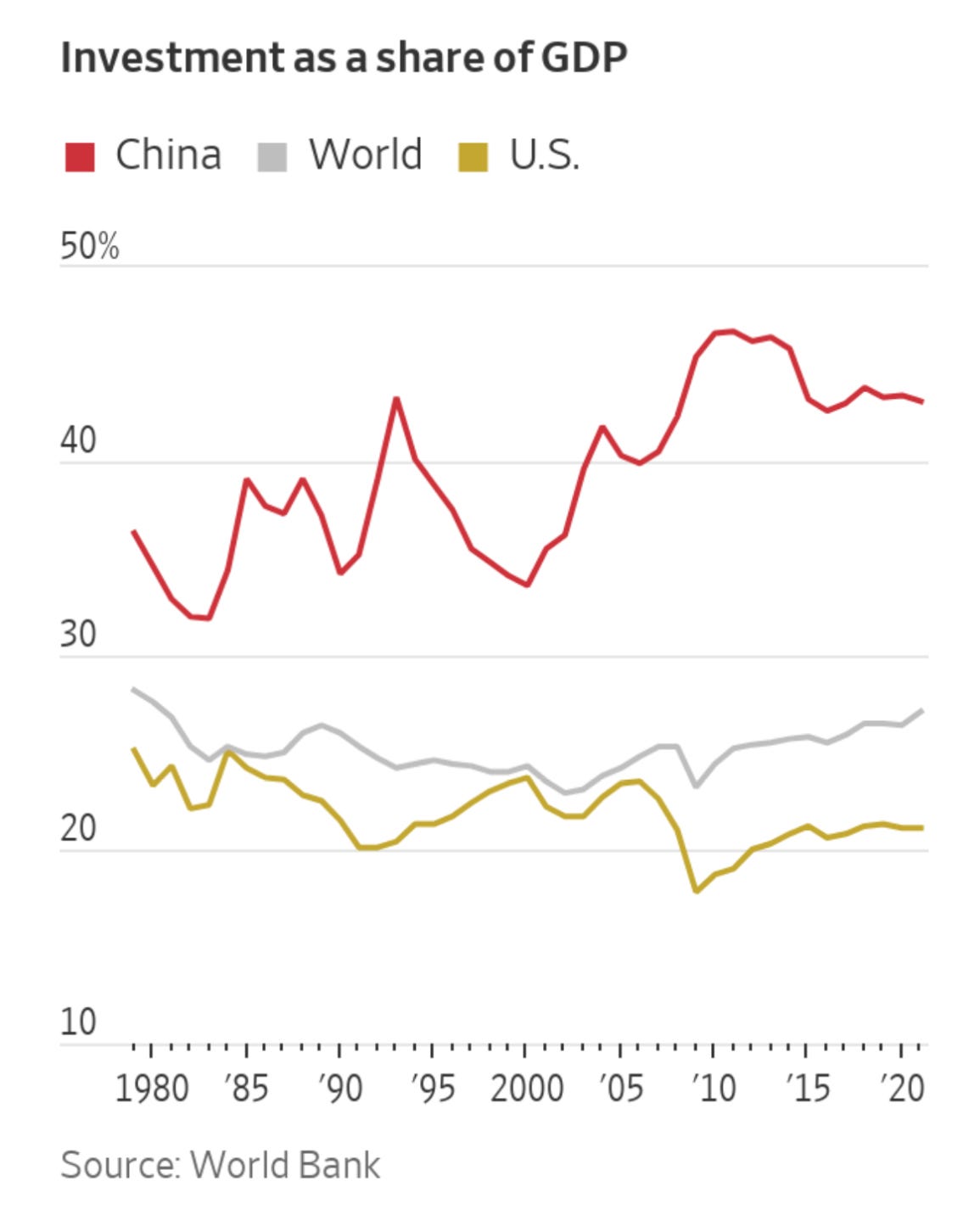

(World Bank, via Wall Street Journal)

But for more than a decade now, economists have been saying that the Chinese economy would need to transition to a model that involved more consumption, less savings, and less capital investment, if it was going to continue to have a sustainable economic model. (What’s meant by this, of course, is continuing economic growth, which may also not be sustainable. But for this article we’ll park that.)

(Source: The World Bank via Wall Street Journal)

The result is that China is currently full of under- or unoccupied buildings and roads, and there is debt everywhere you look in the system:

Parts of China are saddled with under-used bridges and airports. Millions of apartments are unoccupied. Returns on investment have sharply declined... With private investment weak and exports flagging, (local) officials say they have little choice but to keep borrowing and building to stimulate their economies.

There’s lots of detail in the WSJ article that builds up the case about this. It matters because: if you’re not building things that are going to get used, and therefore produce returns on your investment, you’re simply piling up more debt.

The question is: is this a step change or a turning point in China’s economic story, or is it a temporary problem? The jury’s out on this.

The WSJ article is definitely leaning towards the first of these, quoting the economic historian Adam Tooze in support:

“We’re witnessing a gearshift in what has been the most dramatic trajectory in economic history.”

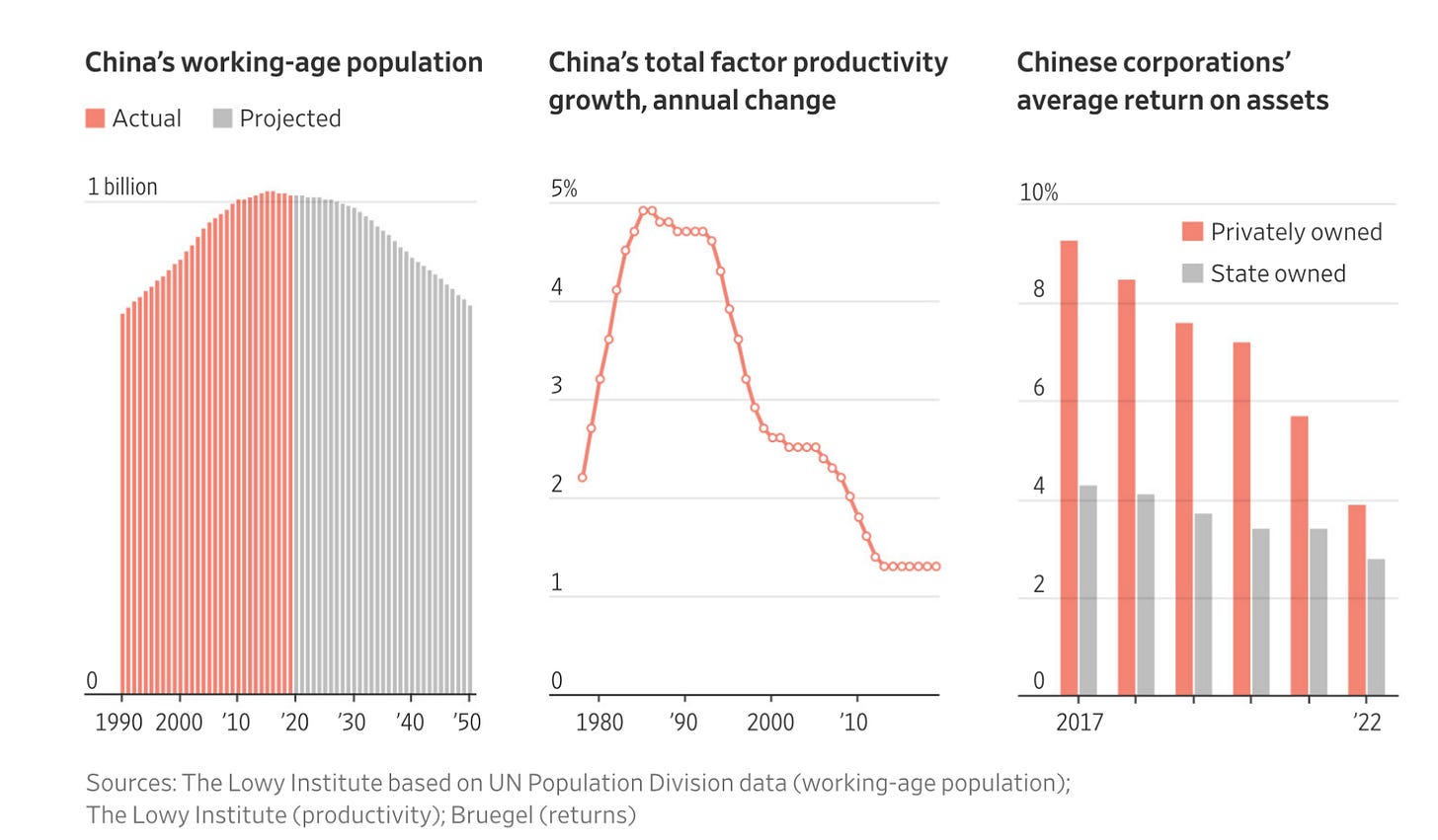

The trend line data doesn’t look great either:

The International Monetary Fund puts China’s GDP growth at below 4% in the coming years, less than half of its tally for most of the past four decades. Capital Economics, a London-based research firm, figures China’s trend growth has slowed to 3% from 5% in 2019, and will fall to around 2% in 2030.

And nor do the underlying factors—whether it’s the country’s ageing population, declining productivity rates, or falling return on assets.

(Via the Wall Street Journal)

At 4% growth—and unlike Japan and South Korea—China will not manage to make the transition from being a middle income country (measured by income per capita) to being a high income country. Some economists think that the economic outcome could be worse than this, and that China might be following the trajectory of Japan in the 1990s, when over-investment in property led to a decade of stagnation.

The difference, though, is that Japan had already reached the ranks of the high income nations when its slowdown happened. China has not. In fact, only a handful of nations have escaped from the middle income level to reach the high income level. FN The World Bank defines a middle income country as one whose per capita gross national product has remained between $1,000 to $12,000 at constant (2011) prices. Typically they get stuck because an export-led model that creates growth leads to rising wages, which means they become less competitive, and growth slows.

This issue is picked up in a recent Reuters’ report, headed ‘Will China ever get rich?’ It covers much the same ground as the WSJ piece but more concisely. But a telling chart shows the different levels of income per capita.

(Source: Reuters)

And there are commentators out there who think that we’re just seeing a blip, caused by various post-Covid adjustments, and that household incomes are increasing and that spending will follow.

It’s also worth saying that the Chinese economy has been repeatedly misjudged by economic analysts over the past decades, partly because the data is hard to read. It’s also the case that readings of the Chinese government’s economic strategy are often coloured by ideology—for example, by distaste for Xi Jinping’s authoritarianism.

For what it’s worth, the economist I tend to take the most note of here is Michael Pettis, partly because he lived and worked in Beijing for a long time. He had a thread on Twitter in August that offered his view of China’s economic position.

In his account, the high savings rate and heavy infrastructure investment were both deliberate and engineered by the government.

This included policies that forced up the savings rate and corralled the resulting savings into a highly controlled banking system that was designed to flood the investment and manufacturing sectors of economy with cheap financing. It also included heavy currency intervention, tough labor restrictions, and a whole series of direct and indirect subsidies to the manufacturing sector that led to explosive growth in infrastructure and made Chinese manufacturers the most competitive in the world.

This was all about government management of the economy. It worked fine while new infrastructure contributed productively to its economy, but China persisted with this policy even once it had passed this point:

it continued with the same model of high savings and now-excessive investment, which led – as in every one of the precedent cases – to asset bubbles, especially in real estate, and an ultimately unsustainable rise in debt.

So, in effect, domestic demand has been suppressed as part of government economic policy beyond the point where it is useful. And in turns that means that domestic demand is too weak to persuade domestic businesses to invest:

Without resolving weak domestic demand, it is all but impossible for China to maintain high levels of economic activity except by maintaining the high levels of non-productive investment that have caused the very malaise it is supposed to cure.

Business investment is weak, in other words, not because of government intrusion but because of weak demand. Government intrusion is the consequence of weak business investment. The way to fix the economy is to fix the demand side of the economy.

In the Reuters’ story, Richard Koo, of Japan’s Nomura Research Institute, worries that lower growth might cause social instability:

"If Chinese people do not reach their Chinese dreams, perhaps you will have 1.4 billion not very happy people over there, which might be rather destabilising."

But Michael Pettis’ analysis suggests that there’s a way out of this economic situation, if the Chinese government wants to take it, that also improves social stability. You could “unlock” the system by using tax stimulus to improve the social safety net, which might then encourage Chinese consumers to save less and spend more. This improves domestic demand and lets the government reclaim the extra taxes that this generates. And makes China’s 1.4 billion people less unhappy.

2: How supermodernity detaches itself from the world

I might be being unkind to the French anthropologist Marc Augé when I say he had one big idea, but the idea that he is best known for is an influential one. It is the idea that extreme forms of modernity—what he calls ‘super-modernity’—have created non-places, which are places that are more or less the same no matter what country you are in.

His book of that name was published in French in 1992, in English in 1995, and with 30 years of hindsight can perhaps be seen as one of the harbingers of the way in which information and communications technologies would reshape the world.

Some of these non-places are associated with travel, such as airports, motorways and their service stations, and hotel chains. Something similar is true of shopping malls and ATMs as well. He doesn’t talk about them, but I couldn’t help but think of the gym as another, more recent, addition to this list.

(Rome airport. Photo: Andrew Curry. CC SA BY NC 4.0)

Augé died recently, and I have been travelling, so his ideas have been on my mind. Unherd also had a short article about him and his work after his death, which I will come back to later on.

The critical feature of super-modernity is that it is self-contained, even self-referential. Non-places also exist only in reference to themselves. This means that every individual’s relationship to a non-place is the same.

It happens that there’s a copy of Non-places posted online, complete with its reader’s annotations. Scanning it quickly to refresh my memory I was reminded that it is written in that discursive style that French academics seem particularly good at. The Prologue also brings to life the idea of the non-place through a “day in the life” of “Pierre Dupont”, on his way to an airport, which makes the concept of non-places more tangible. The first chapter is a discussion about the limits, or not, of anthropology. His style, all the same, makes it hard to summarise. But let me try.

(1) In some ways the book is a conversation with the ideas of Michel de Certeau, who was something of a 20th century French polymath who spent time in one of his books talking about the relationship of place and space.

(2) Modernity suppresses the past, but also seeks a relationship with it:

The presence of the past in a present that supersedes it but still lays claim to it: it is in this reconciliation that Jean Starobinski sees the essence of modernity... 'Bass line': the expression Starobinski employs to evoke ancient places and rhythms is significant: modernity does not obliterate them but pushes them into the background. (p75, 77)

Supermodernity, in contrast, disconnects itself from place, described here in the terms used for “anthropological place”, which

want to be—people want them to be—places of identity, of relations and of history. (p52)

(3) Supermodernity has emerged from the combination of three factors, each of which can be characterised as a form of “excess”. The first is time: there is “an overabundance of events in the contemporary world” (p30):

(I)t is our need to understand the whole of the present that makes it difficult for us to give meaning to the recent past. (p30)

The second is ‘space’, where our steps in space, and our photographs of it, make our human world seem smaller; where the world itself also seems smaller because almost everywhere is only a few hours away (if you have the means and privilege to travel); and where media brings the world into our homes immediately and all the time (pp31-32).

The third is an excess of ‘ego’, or of individualism. “In Western societies, at least, the individual wants to be a world in himself.” (p37).

(4) These characteristics constitute a certain type of place with which the individual has a particular type of relationship. This relationship is defined by text and symbols:

(T)heir 'instructions for use', which may be prescriptive (‘Take right-hand lane'), prohibitive (‘No smoking') or informative ('You are now entering the Beaujolais region’). (p96)

He has a little flourish with this idea a few pages on in the context of the supermarket:

The customer wanders round in silence, reads labels, weighs fruit and vegetables on a machine that gives the price along with the weight; then hands his credit card to a young woman as silent as himself- anyway, not very chatty - who runs each article past the sensor of a decoding machine before checking the validity of the customer's credit card. (pp99-100)

Of course, the non-place never completely escapes the place:

Place and non-place are rather like opposed polarities: the first is never completely erased, the second never totally completed; they are like palimpsests on which the scrambled game of identity and relations is ceaselessly rewritten. But non-places are the real measure of our time. (p77)

(Image: Verso)

In his Unherd article Mark Blacklock adds some useful commentary to all of this. For example:

(A)ccess to the sort of anonymity (non-places) allow is granted only if we provide evidence of our individuality, in the form of identification documents; Augé foresaw that supermodernity would increasingly require us to prove who we are. He also goes so far as to speculate that non-places are terrorist targets not only for practical reasons, but also because they refuse the very idea of the historical territories that nationalist causes wish to restore.

Blacklock also suggests that Augé’s interest in airports and motorways links him, at least by association, with the British literary figures J.G. Ballard and Ian Sinclair, whose work engages with non-places:

Ballard’s 1997 essay on airports for Blueprint magazine comes across as a piece of rogue anthropology. “We are no longer citizens with civic obligations,” he writes, “but passengers for whom all destinations are theoretically open.” ... (S)upermodern life inevitably channels us into these non-places: we have no choice but to enter. We therefore need to learn how to endure them.

One final note: Augé was deeply embedded in French culture. For a reader like me who is less familiar with French literature and French thinkers, the range of references in this short discursive essay is a bewildering delight.

j2t#493

If you are enjoying Just Two Things, please do send it on to a friend or colleague.

Love the piece on non-places. Thank you for expanding my thinking.