5 October 2022. Families | Photography

Abolishing the family. // Eamonn McCabe on portraits and photography

Welcome to Just Two Things, which I try to publish three days a week. Some links may also appear on my blog from time to time. Links to the main articles are in cross-heads as well as the story. A reminder that if you don’t see Just Two Things in your inbox, it might have been routed to your spam filter. Comments are open.

1: Abolishing the family

The saying goes that “it takes a village to raise a child”. The converse might be true as well. All the same, there’s nothing quite like reading a review of a book called Abolish the Familyto make you realise how visceral some of your beliefs are.

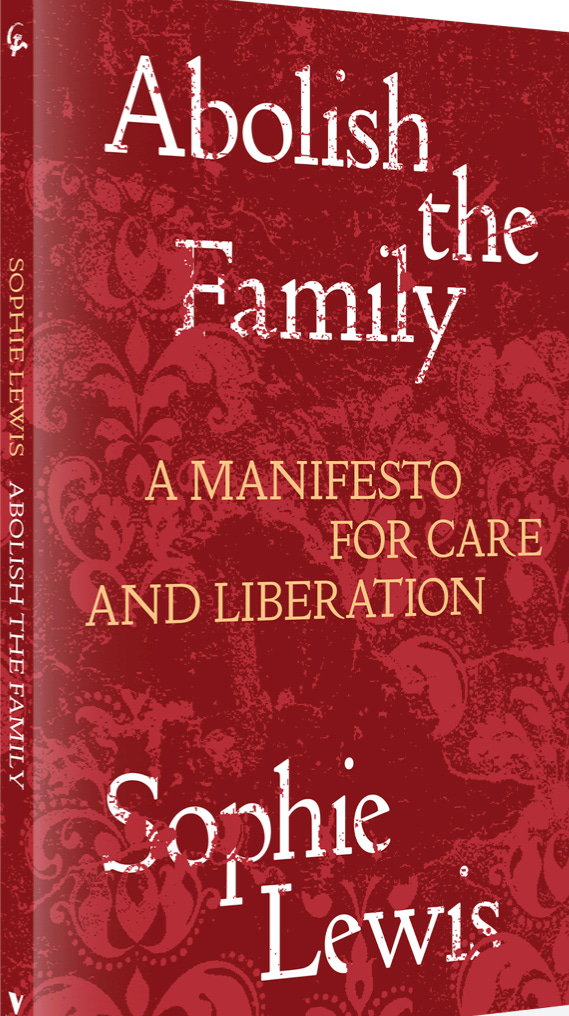

The book is by the American academic Sophie Lewis, and it is reviewed in the New Statesman by the historian Erin Maglaque, outside of the NS’s usually tightly maintained paywall.

The review starts with the 19th century French utopian Charles Fourier, who wanted to abolish the kitchen in the pursuit of women’s emancipation:

Men and women would live collectively, cooking instead in open common kitchens and free canteens, serving up marmalades and pastries and lemonades in abundance… Their communal life would relieve women – in the words of the radical feminist and utopian architect Alice Constance Austin – of “the thankless and unending drudgery of an inconceivably stupid and inefficient system by which her labours are confiscated”.

And once you start with the kitchen, who knows where you might end up?

A bit of self-governance here, some collectively organised childcare there: begin with the kitchen, and we might end up with a whole new society. This is the premise of the revolutionary politics of family abolition.

(Well, certainly abolish the 1961 Hotpoint all pink kitchen. Image via Joe Wolf/flickr. CC BY-ND 2.0)

It’s quite a long article, and carefully argued, and I’m probably not going to do it justice here. The heart of the case against the family, though is that it privatises care, wrapping it up in skein of legal and economic arrangements that produce poor outcomes:

Children are private property, legally owned and fully economically dependent on their parents. The hard work of care – looking after children, cooking and cleaning – is hidden away and devalued, performed for free by women or for scandalously low pay by domestic workers. Even the happiest families, in the words of the writer Ursula Le Guin, are built upon a “whole substructure of sacrifices, repressions, suppressions, choices made or forgone, chances taken or lost, balancings of greater or lesser evils”.

The book is subtitled ‘a manifesto for care and liberation’, and perhaps should be read alongside some of the other books on care we’ve seen over the past few years. Lewis, for her part, isn’t naive about the kinds of responses that her argument produces: “So! The left is trying to take grandma away, now, and confiscate the kids, and this is supposed to be progressive? What the fuck?”

Of course, there is a long history of this argument wrapped up in a range of politics, from the progressive to the revolutionary. Maglaque traces the threads from the Russian revolutionary Alexandra Kollontai to the American National Welfare Rights Organisation in the 1970s, via the ‘60s writings of Shulamith Firestone and the early ‘70s activism of the gay liberation movement.

In making her argument now, Lewis draws on some of the thinking that has moved the prison abolitionist argument forwards:

Ruth Wilson Gilmore… argues that the prison abolition is not only an ending, but the creation of something new: real justice. The family, like prison, seems an inevitable part of our social fabric; and yet we do not necessarily want to know what happens within them… Abolition brings a new world into being that couldn’t have been imagined before the struggle to abolish the old one.

And as with prison abolition, writing about the family in the American context is scored through with complex racial politics. The review quotes the American scholar Saidiya Hartman on this:

the black woman’s caring labours are both the product of slavery and a means of survival; a refuge, a creative source of sustenance, in the face of that same violence. “This brilliant and formidable labour of care,” Hartman writes, “paradoxically, has been produced through violent structures of slavery, anti-black racism, virulent sexism, and disposability.”

Lewis’ answer here seems to be that it would be better to live in a world where we didn’t need such refuges. All the same, there’s something challenging going on here. Far more than prison abolition, family abolition unravels some of our deepest psychic structures. As Maglaque writes,

family abolition calls into question some of our most deeply held notions of ourselves: about kinship, belonging, identity; about what we consider natural, about what can be lived differently.

At the same time, maybe one of the things that happened during the pandemic was that behind our locked down doors some of the shine was taken off the idea of the family:

Burned out from pandemic parenting, facing immense childcare shortages and costs, women are leaving the workforce in record numbers, and in the US, forced birth and baby formula shortages are making crisis-parenting the rule, not the exception. The call for a revolutionary way of reconfiguring how we care for each other is more essential than ever, and Lewis’s manifesto is an irrepressible spark to our very tired imaginations.

All the same, even the basic political demands that might be the platform for a fraction of this change seems as utopian as Fourier right now:

free 24-hour community-organised childcare; breakfast and after-school clubs; community kitchens; expanded food stamp programmes; the freedom from work – these were middle-of-the-road demands that now appear on the farthest possible horizon of progressive feminist politics.

Certainly in British politics, the rhetoric of the ‘family’ is as strong as ever, stronger perhaps. New Labour’s endless appeals on behalf of ‘hard working families’ has morphed seamlessly in the 2020s to “a future where families come first”. Kitchens for everyone, perhaps. Maclague nods to her own (middle-class) childhood in which the family seemed to be managed as “a population of high-achieving, high-investment tiny entrepreneurs”.

But the purpose of the utopian imagination is to make the present seem strange, in order that we can imagine different futures. Certainly reading the review, the present did seem strange—even as the imagined future was indeed a bit of a psychic shock.

2: Eamonn McCabe on portraits and photography

I feel as if I grew up with the photography of Eamonn McCabe, who has died this week, but I know that’s not completely true. He came to prominence as a sports photographer during the 1970s, having given up on music photography, his first love, because he disliked the British glitter bands (Alvin Stardust, Gary Glitter, and so on).

And my father loved sports and photography, and McCabe worked for The Observer, so we’d see his work in the house every week.

The Heysel disaster in 1984 did for his love of sport what glitter had done for music, and he became a picture editor at The Guardian. There’s a portrait of him in the National Portrait Gallery picture editing away, which I’ve shared here because it is in a public collection and was given to the Gallery by McCabe. It’s by Beth Elliott.

(Eamonn McCabe by (c) Beth Elliott, 2007)

After that he returned to photography, mostly to portraiture, and there are some fine examples of these on his website. I’ve shared a couple of these below. The portraits of actors tend to be less interesting than the others, perhaps because they spend their lives disguising themselves

I’ve taken most of these biographical details from an interview he gave to Digital Camera World in 2010, which smartly republished it online when they heard of his death. The interview is by Geoff Harris.

They also republished his tips on portrait photography, which are certainly worth re-sharing here:

1 Focus on the eyes

In portraits; I like to get my subjects gazing to camera. If you’re nervous as a photographer, your subjects look away.

2 Experiment with light…

…but keep it simple; I just use one softbox with one light source. If you complicate things with too many lights, you can get into such a state that it will affect the picture.

3 Watch your back

You really must get the background right when taking photographs of people. Indeed, I’m a great believer that if you get a good background, you’re halfway towards getting a good portrait. It’s pointless taking a nice shot of someone and then spoiling it with extraneous objects such as trees sticking out of the tops of their heads in the background!

I’ve reproduced some of the photographs from his website below, which are obviously all his copyright.

In the interview he’s interesting on the pleasures of portrait photography:

“I’m proud of a portrait if it lasts – if it’s fresh and it stands the test of time, then I’ve cracked it. People still enjoy the portraits I took of the writer Zadie Smith and the actor Jude Law, for example. The hardest job is taking a portrait of somebody who you wouldn’t recognize, like a writer or a poet who shuns the limelight.”

But he also notes a couple of trends that make the work harder to do well, or at all. The first is the way in which access to the rich and famous is increasingly tightly managed:

“When taking a portrait of a famous sitter, you have to work really fast now, and deal with armies of PRs. That’s something else that’s changed for the worse. I only got 30 seconds to photograph Bill Gates, for example.”

The second, especially on live sports events, is that the video is so ubiquitous that it’s easier to take the images from video than have photographers do it.

McCabe also worries that the stills photographer could become a thing of the past as picture editors resort to pulling images from HD video feeds. “It’s happening more and more, and you can certainly imagine a time when all the still shots of the FA Cup final are just pulled from video.”

And certainly, you wouldn’t have got his memorable picture of Diego Maradona from a video. The pictures below, from his website, are all for sale, and not at silly prices.

(Diego Maradona. (C) Eamonn McCabe)

(The musician Ray Davies. (C) Eamonn McCabe)

(The artist Bridget Riley, in a very colour co-ordinated studio. (C) Eamonn McCabe)

j2t#377

If you are enjoying Just Two Things, please do send it on to a friend or colleague.