5 March 2023. Rewilding | Photography

Raising money for rewilding. // ‘A photograph is always a record of a relationship’

Welcome to Just Two Things, which I try to publish three days a week. Some links may also appear on my blog from time to time. Links to the main articles are in cross-heads as well as the story. A reminder that if you don’t see Just Two Things in your inbox, it might have been routed to your spam filter. Comments are open. Have a good weekend.

1: Raising money for rewilding

Jeremy Leggett was a solar energy pioneer. These days, he is devoting his time to rewilding parts of the Scottish Highlands. This is a tricky subject, as the Scots site Bella Caledonia noted last year in a discussion of the term ‘Green laird’. (If you’re not that familiar with the history of Scots land ownership, the word ‘laird’ is the problem here.)

I’ve been following Leggett’s rewilding project, Highlands Rewilding, since he started it a couple of years ago, and he’s sensitive to these criticisms. The project has, however, acquired some momentum recently because Highland Rewilding got the opportunity to acquire a third estate, and it has been raising money to do this.

(Tayvallich Estate. Photo: Rewilding Highlands.)

The offer closed this week, successfully, and—I think by coincidence—Leggett was invited to Balmoral (the privately owned residence of the British Royal Family in the Highlands) to talk about the project. It’s not clear which royals, if any, were in attendance. The Royals definitely fulfil the definitional requirements for ‘lairds’.

What’s interesting about the speech, which was shared in a project newsletter this week, is that he talks in a bit of detail about how you go about raising money for this type of rewilding scheme. This matters, firstly, because rewilding isn’t cheap:

In the UK’s case, the Green Finance Institute estimates that nearly £100 billion will be needed (for nature restoration) over the next ten years. Scotland’s share of that is some £20 billion. That is an Everest of a target. Those of us trying to assault the summit are not even in the foothills yet. The main source of sums this big has to be the financial institutions: investment funds, pension funds, insurance companies and the like.

Part of Leggett’s purpose in this work is to find a way in which these institutions can be persuaded to invest in nature restoration:

Our efforts are about much more than one progressive company trying to grow. Given the existential nature of the threats, and the fact that no financial institution has yet placed a major investment in nature recovery, a towering question arises. It is actually whether or not capitalism has a survival reflex. Personally, I believe it will prove to have one, and I set up Highlands Rewilding in large part to try and help in the global effort to trigger it.

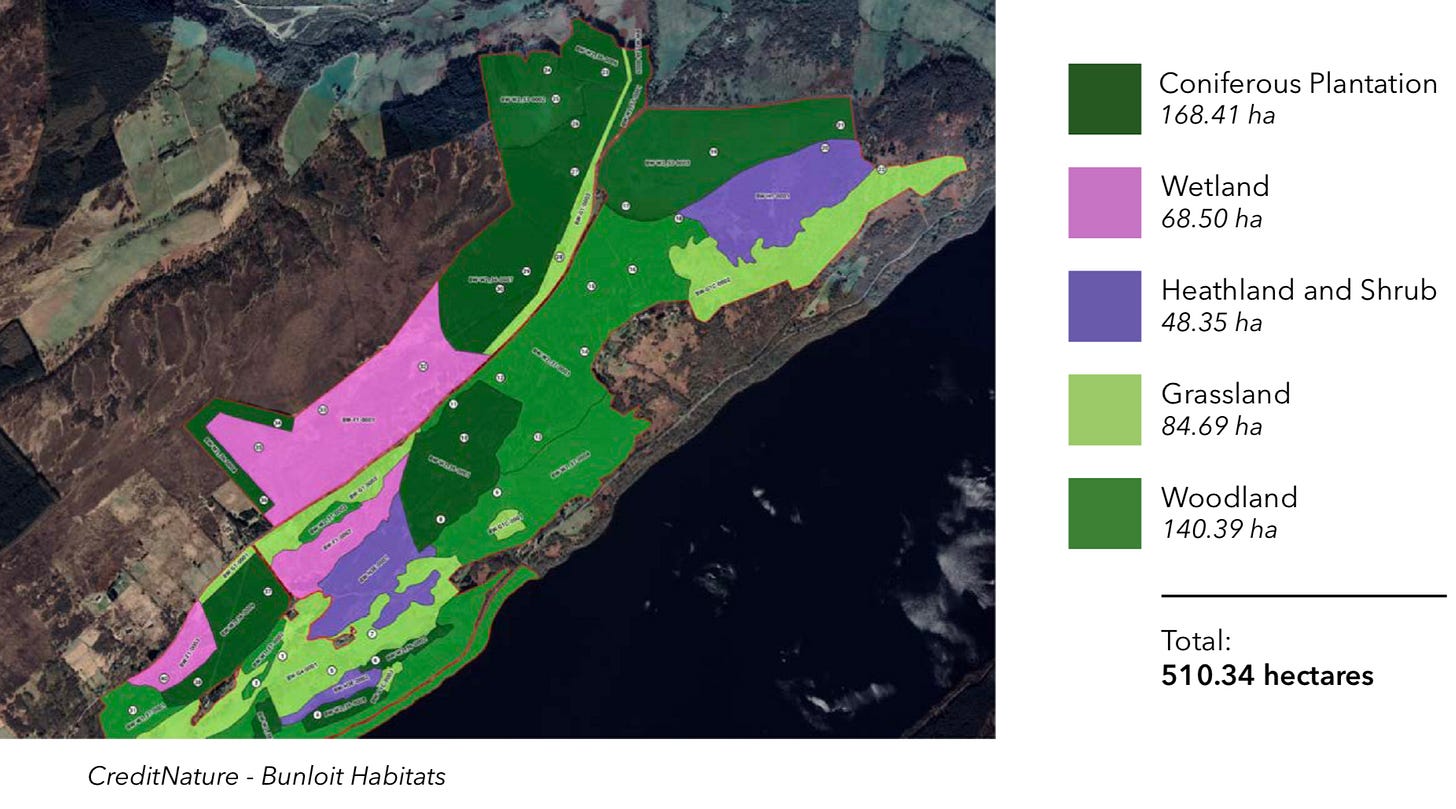

The business model of Highlands Rewilding works like this. The business has twin goals of nature recovery and community prosperity through rewilding. It plans to scale this in two ways. What they call ‘vertical’ scaling involves adding to their portfolio of properties—hence the fundraising for the Tayvallich Estate (adding to the existing estates, Bunloit in Inverness and Beldorney in Aberdeenshire). What they call ‘horizontal’ scaling involves building a “data-driven land-management service offer”. The first report they did, in 2021, mapping and modelling the carbon and biodiversity of Bunloit, is online.

(Mapping the carbon and biodiversity landscape. The conifers will have to go. Image: Rewilding Highlands.)

The Tayvallich estate, in Argyll, has been well cared for and offers an opportunity to extend its temperate rainforest and sequester carbon offshore in kelp and seagrass.

The retail fundraising has gone well. They met their initial £500,000 ($600,000) target quickly and have since pushed through to a ‘stretch target’ of more than £800,000. They’ve decided to leave the offer open for longer, to continue to test the market and create a fund for further opportunities.

So who is willing to invest in rewilding? Leggett spells it out in his speech. There are three types equity they are interested in:

The first is equity from citizen rewilders, via crowdfunding. The second is equity from the all-important financial institutions. The third is the rest. This includes equity from investors of the kind who invested £7.6 million in our start-phase round, our 50 Founding Funders: affluent rewilding enthusiasts, family offices, foundations, trusts and forward-looking companies.

In the scheme of things, the first is relatively small, certainly in terms of the kinds of totals we need to invest to take rewilding seriously. But it allows interested individuals to be involved:

This approach, we have found, tends to win approval in communities, in government, and among the bigger investors too... our experience is that it is popular enough, across the stakeholder spectrum, to have a good chance of succeeding.

The third type has also been successful The current funding round has drawn in new funders. Between types one and three, they have now raised enough money to buy Tayvallich—something over £10 million ($12m), according to some reports.

But: it’s the second one where the money is, and so far, they haven’t got these investors to invest in rewilding. They might do this: but they haven’t done it yet.

Several of the funds that we courted told us some version of “you have made great progress; we know there will be a growth market in nature recovery, but please come back in 6 to 12 months.”

Some policy innovation might help, and the Scottish Government is working on this, and so does the crowdfunding campaign.

Fund managers have told us that our mass ownership works well for them, because of the element of social licence it brings. Stated another way, the more that citizen rewilders invest at the £50 to £100 level, the more the financial institutions are likely to invest at the £50 million to £100 million level.

Of course, these financial institutions are the same ones, broadly, that have financed the activities that make carbon sequestration and biodiversity. In the present political climate, I can see that Leggett’s approach—slow persuasion—is probably necessary, while waiting for the policy incentives to improve. It’s also possible that he’ll discover that capitalism doesn’t have a survival reflex. But in a parallel universe somewhere, these institutions are paying reparations to the planet.

2: ‘A photograph is always a record of a relationship’

It’s probably fair to describe the photographer Susan Meiselas as ‘a veteran’. She’s in her 70s now, and has been a working photographer for 50 years or so. Her work spans the range, from covering the war in Nicaragua to Kurdistan opposition to Sadam Hussein to more intimate portraits of strippers, and self-portraits.

Her work is being honoured with a retrospective in Antwerp, called ‘Mediations’, that runs until the beginning of June. There’s also a new book on her work, On the Frontline.

She has been involved with the photographers’ co-operative Magnum, which marked the opening of the exhibition by re-running an article from 2018 in which she talked about the principles that have informed her photography practice.

(Susan Meiselas Self Portrait. 44 Irving St. Cambridge, MA. USA. 1971. © Susan Meiselas | Magnum Photos)

'Being photographed’

The photograph above, taken in the boarding house where she lived in her early 20s, was part of her early exploration of what photographing and being photgraphed being involved.

I am present, but I want to avoid the focus on myself. I am not a ‘fly on the wall’: I don’t pretend not to be there, but I am not the ‘story’. I might be the bridge, the guide, and in some sense the collaborator with the subject”.

The reason this matters is that in some way a good portrait involves a private moment:

To make a good portrait, you need to reveal a private moment, which can feel like an act of theft.

'Creating narrative’

At around the same time, she worked with strippers in several American states, photographing them both on-stage and off. When it was shown, the photographs were seen with recordings of the women talking about their lives. The book included texts from these interviews.

I don’t see myself as an artist just working within a community of artists. I am most interested in the community from which the work actually comes... (This work) was first seen on walls, not printed pages. The women brought me in, and the book later brought a hidden world to public attention, sharing a complex story from the inside out.”

'Voice’

Meiselas has looked for ways to continue collaborating with her subjects both during the initial photography and after they’ve been photographed:

In her first work in Massachusetts, she showed the images she made to the subjects in them, and asked how they saw themselves represented in her images... “I was experimenting with how to bring their voice into the work. The subject has to want me to be there for me to feel that I can be there.”

Similarly when she went back to Portugal for an exhibition of photographs from a neighbourhood in Cova de Moura, a Cape Verde neighbourhood on the edge of Lisbon, she knew that they wouldn’t come to the city centre to visit a gallery. So she ran workshops with people from the community and set up an exhibition on the street in Cova de Moura of their work and hers.

'Returning and giving back’

Meiselas worked in Kurdistan first to document Saddam Hussein’s campaign against the Kurdish people. She went on to work with Kurdish scholars and the community to create a visual history, gathering photographs from Western archives and family collections which were shown in an exhibition and a book. A second edition of the book gave her a chance to update it and get some of it translated into a Kurdish language, Sorani. But the books were banned in Turkey, so it wasn’t possible to take them across the border to Kurdistan:

The books were reprinted in Spain and copies were shipped by boat to Dubai where they could be sent as airfreight straight to Kurdistan. There, Meiselas helped to distribute them to libraries, universities, families and all who had contributed.

“A photograph is always a record of a relationship. People had contributed photographs they had made or found and given them to a stranger in the interests of a history that was very precious to them. The cycle of return of what had been generously shared felt complete”.

(Susan Meiselas Kurdistan, Iraq. 2007. © Susan Meiselas | Magnum Photos)

Update: Ukraine

I wrote about Ukraine earlier this week, and since then I have come across an extraordinary article in the European Review of Books. It is about a visit to Ukraine made by the Italian writer-journalist Curzio Malaparte to the Ukraine in 1941. Visit isn’t quite the right word. Malaparte was covering the German invasion.

Dorogo is burning, alighting the early evening sky. Malaparte, looking for a place to spend the night, rides forth in an eerie glow. When he slows down a bit to get his bearings, he is startled by voices high above his head. He hears a rustling up in the leaves and branches of the trees that line his path, but can see only the dark outlines of their trunks. Suddenly he hears shrill voices and furious laughter. Or is he imagining things?…

But then, high above his head, he really does hear human voices, in German, Russian and Hebrew, asking: « Who are you? What do you want? » Malaparte doesn’t know what else to do but to answer:

« I am a man; I am a Christian, » I said. A shrill laugh rippled across the black sky. It faded away into the distance and was lost in the night. … Scornful laughter greeted my words. It drifted high above my head into the distance, and gradually died away in the night. « And aren’t you ashamed of being a Christian? » shouted the voice. I was silent.

Malaparte was a complex character who managed successfully to navigate the complexities of the period between the war, and war-time Italy. In his long, long article, Mathieu Segers traces the connections between Malaparte’s experience of those years and our own. Hemingway gets a look-in too.

j2t#432

If you are enjoying Just Two Things, please do send it on to a friend or colleague.