5 June 2023. Animals | AI

The ethics of eating animals, revised? // Tech bros say the sky is falling in. (#463)

Welcome to Just Two Things, which I try to publish three days a week. Some links may also appear on my blog from time to time. Links to the main articles are in cross-heads as well as the story. A reminder that if you don’t see Just Two Things in your inbox, it might have been routed to your spam filter. Comments are open.

1: The ethics of eating animals, revised?

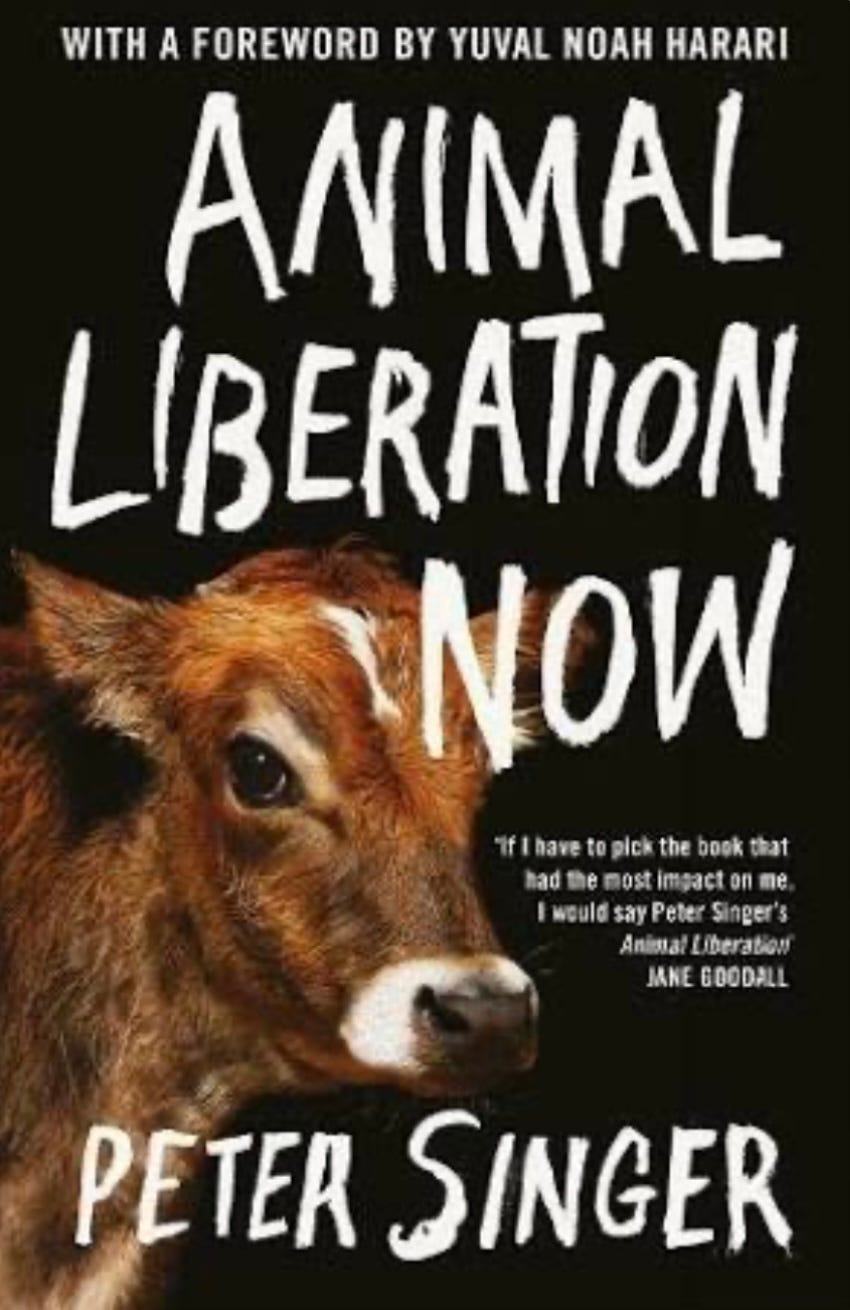

The current issue of New Scientist has a group of interesting articles about animals and farming, including a short interview with the Australian philosopher Peter Singer. It’s all behind a paywall, and hard copies of the magazine seem to have an increasingly expensive pennies per page ratio, so I’m going to include some extracts here, starting with Singer.

He is obviously best known for his book Animal Liberation, published in 1975, which defined a lot of landscape of debate around vegetarianism, veganism, animal welfare, and animal rights. His core argument then was that

“we should give equal weight to similar amounts of pain and pleasure, irrespective of species. It’s just as bad if pain is inflicted on a human or a dog or pig.

Since then, to a considerable extent, general opinion has moved towards Singer over the intervening five decades. All the same, he has now revised Animal Liberation for contemporary audiences. Part of this is because some of the things he wrote about then, such as the use of animals in research, have changed, at least a bit, in the meantime. (We no longer force beagles to smoke in labs, for example.) Part of it is because the original book barely touched on climate change.

(Grass-fed ruminants hard at work in a field: maybe changing the ethics of eating meat. Photo by RF Vila, via Wikipedia, CC BY-SA 4.0)

Madeleine Cuff is the New Scientist interviewer:

How has your thinking around the eating of animals evolved since 1975?

I've become a little more open to the idea that if we rear animals in ways that give them good lives and take care to make sure that they do not suffer when they are killed, then that's a defensible ethical position. In the first edition, I rejected that. But I have thought about the whole issue more since then. It relates to some difficult philosophical questions about bringing new beings into existence and giving them good lives. Is that a plus?... It's still not my view, but I now see some of the difficulties in rejecting it. I regard it as a kind of unsolved philosophical problem.

Introducing climate change into the discussion also opens up new issues. As Madeleine Cuff says to Singer, “eating ethically to maximise animal welfare and eating ethically to minimise climate change aren’t always the same”. It is, for example, to get beef from animals that have lived their lves on grass, but:

(T)he greenhouse gas emissions are very high from ruminant animals because they produce methane, an extremely potent greenhouse gas. By comparison, chickens don't produce methane and so there's much less of a climate change implication in eating chicken. But most chicken is factory-farmed. So, if people simply switch from beef to chicken for climate reasons - OK, they are reducing their greenhouse gas footprint, but they're causing a lot more suffering to animals. I think it's better to avoid both and to follow a plant-based diet.

Singer argues in the interview that it would be reasonable for governments to impose taxes on beef, lamb, and dairy, which are doing the most damage to the climate, because it’s a market failure that the price of those goods doesn’t include the harm they do to other people. And of course, ethically, that harm is being done disproportionately to the poorest people in the world, who can do least to influence climate change. (This isn’t so much a philosophical argument as an argument about the economics of externalities.)

Cuff asks him if he can foresee a world in which eating meat and dairy becomes morally acceptable. His answer: eventually, probably:

The long-term development of ethics and morality will expand the circle of moral concern. I think that will, in the long run, lead to the inclusion of non human animals in an ethical framework that means that we cannot treat them as we are now treating them. But its very hard to put a time frame on it. It's a really big change. It might be 50 years, but it might be over a century. If we get products that taste and chew like meat and have the nutritional qualities of meat, but don't come from animals, then we may get there a lot faster.

Incidentally, he got asked about the proposal to farm octopus in the Canary Islands, which I wrote about here. He’s against it: no, he’s “totally appalled”. (For more on octopuses, also see below).

The magazine’s leader column goes further into the issue of how best to resolve possible conflicts between ethical and environmental issues. It suggests that there are broadly two options:

One is futuristic: increased intensification of arable farming on smaller areas of land, and technological advances such as precision fermentation to provide animal protein. The other is to revert to ways of the past and rebuild systems known as regenerative farming.

Of course, the notion that regenerative farming can feed the world is always given short shrift—I’ve facilitated quite a lot of workshops over the years where it’s more or less been dismissed out of hand, even though only 30% of the world’s food, even now, comes from industrialised farming systems; the share of its impacts on climate and biodegradation is far higher. (From memory this figure is from Dougald Hine’s book At Work in the Ruins.)

The leader suggests that there is some evidence that such regenerative food systems systems can be as productive as industrial systems, without creating the same level of damage. There’s also an open question about whether non-industrial food systems will generate as much waste as industrial systems do.

We might also just have to accept that food does cost more: that the last seventy years of cheap global food, at least in the global North, was a blip rather than a trend. The New Scientist leader concludes that systemic change is needed:

Regenerative farming deserves a fair hearing. Until then, food writer Michael Pollan's advice is best: "Eat food. Not too much. Mostly plants."

2: Tech bros say the sky is falling in

I’ve been trying not to write about AI, but it follows you around at the moment. And certainly the recent “statement” in which 1,000 tech leaders, academics, and others say at telegrammatic length that they’re concerned about the long-term risks of AI is a mysterious thing.

AI’s a noisy area right now, so just to be clear: this statement is not the same thing as the open letter that was signed by Elon Musk, Sam Altman, and others back in March. That was headlined: “We call on all AI labs to immediately pause for at least 6 months the training of AI systems more powerful than GPT-4.”

In case you’ve not being paying attention, here’s last week’s statement in full: all twenty-two words of it:

“Mitigating the risk of extinction from A.I. should be a global priority alongside other societal-scale risks, such as pandemics and nuclear war.”

When you look at what it says, and who has signed it, it reads a bit like the bloke outside a bar who is desperate not to get into a fight, yelling “Hold me back, hold me back”.

(Is that all there is? Source: Center for AI Safety.)

The first obvious objection to the statement is that most of the people who have signed the statement have between them the resources and the social capital to organise the process of taking such claimed risks more seriously.

Meredith Whittaker, squeezed out of Google for raising ethical issues, and now President of the Signal Foundation, made this point in Fast Company:

“Let’s be real: These letters calling on ‘someone to act’ are signed by some of the few people in the world who have the agency and power to actually act to stop or redirect these efforts,” Whittaker says. “Imagine a U.S. president putting out a statement to the effect of ‘would someone please issue an executive order?'”

The second objection is the question of whether it’s true or not. There are plenty of computer scientists out there who say that the prospects of an “extinction-level risk” from AI are non-existent, unless we’re going to die out as a species under the weight of terrible prose.

The third is that the list of “societal scale risks” that AI is suddenly ranged alongside—pandemics, nuclear war—seems myopic given the risks posed by climate change and biodiversity. The effective altruists have a blind spot about this as well, but it makes you think that the tech bros need to get out more.

I’m generally a believer in the principle of Occam’s razor—that you should prefer simpler explanations to more complex ones—and I think it’s likely that the technology community (a) does believe this; (b) that culturally they’re not attuned to listening to voices outside of their groupthink; and that (c) this was the most complicated statement they could agree on.

But it’s also worth noting that there are plenty of people out there who have suggested more cynical explanations. The easiest way to summarise this is that by mentioning “the risk of extinction” it’s a kind of “look over there” strategy, distracting attention from potential real short-run harms from AI.

Fast Company quoted a tweet from the University of Washington law professor Ryan Calo:

“If AI threatens humanity, it’s by accelerating existing trends of wealth and income inequality, lack of integrity in information, and exploiting natural resources.”

And Meredith Whittaker makes a related point in the article:

Whittaker believes that such statements focus the debate on long-term threats that future AI systems might pose while distracting from the discussion about how very real harms that current AI systems can cause— worker displacement , copyright infringement , and privacy violations , to name just a few issues. Whittaker points out that a significant body of research already shows the harms of AI in the near term—and the need for regulation.

At his blog, summarising his Bloomberg column, the economist Tyler Cowen suggested that whatever the arguments about the qualities of the statement, it was terrible politics. In one line, his argument is:

Sometimes publicity stunts backfire.

He has several notes on this. The first is the risk of using words like “extinction”, which attract the attention of the security establishment.

The second, as discussed above, is that many of the people who have signed the statement are influential enough to agree an industry-wide code about managing the perceived risks they see. (This isn’t a system like the finance sector where you need someone else to turn off the music so that everyone stops dancing.)

The third is the narrowness of the representation—mostly California and Seattle, with a flavour from Toronto and the UK. If you’re trying to build a political campaign, you’d need to be a bit broader.

Then, there’s the brevity of the statement itself, which opens up the question of, “Is that all there is?”:

Perhaps this is a bold move, and it will help stimulate debate and generate ideas. But an alternative view is that the group could not agree on anything more. There is no accompanying white paper or set of policy recommendations.

And finally, because the statement is so short, and because there is nothing in the way of supporting documents, it undermines the credibility of the statement. In most areas where industry and technical experts agree that something is an issue, they can also agree—at the very least—on some first steps to take to do something about it:

If some well-known and very smart players in a given area think the world might end but make no recommendations about what to do about it, might you decide just to ignore them altogether? (“Get back to me when you’ve figured it out!”) What if a group of scientists announced that a large asteroid was headed toward Earth. I suspect they would have some very specific recommendations, on such issues as how to deflect the asteroid and prepare defenses.

In contrast: the earlier Open Letter went on for pretty much most of two pages, and did also come with a white paper’s worth of policy statements, even if they were published slightly later.

But this time around, not so much. Here we have a big chicken-licken type statement (“the sky is falling down”), but don’t even get another 22 words on where to start dealing with it. Chicken-licken? Well, it turns out that chicken-licken’s situational analysis wasn’t good and it didn’t turn out well for the poor creature, or for most of their friends.

Update: Octopus

Peter Curry has written a long, long, post on octopus intelligence at his King Cnut Substack newsletter. I’ll be honest: unless you’re researching this area, it’s probably as much as you’re going to need to know about the neuroscience of octopi, but they are endlessly fascinating creatures and there are some fascinating bits in the post, which is an extended review-cum-discussion of Peter Godfrey-Smith’s book, Other Minds. Here’s an extract:

Octopuses can’t recognise themselves in the mirror test, where you put a dot on an animal, show them a mirror image of themselves, and see if they try to remove the dot. But they can differentiate between humans, because they fire jets of water specifically at experimenters they don’t like. Octopuses may have good other-vision and bad self-vision.

They have been known to play a version of marine tennis, with two octopuses blasting jets of water at a floating pill bottle across a tank. Some octopuses don’t do this. Some do. The ones that do follow a similar sequence to children interacting with new objects, where they move from “What is this object?” to “What can I do with this object?”, with the answer, disappointingly, being tennis.

j2t#463

If you are enjoying Just Two Things, please do send it on to a friend or colleague.