5 July 2022. Work | Systems

Reimagining work for the 21st century. // A government systems thinking guide

Welcome to Just Two Things, which I try to publish daily, five days a week. Some links may also appear on my blog from time to time. Links to the main articles are in cross-heads as well as the story. And a reminder that if you don’t see Just Two Things in your inbox, it might have been routed to your spam filter. And that Comments are open.

1: Reimagining work for the 21st century.

The social innovator Hilary Cottam has been writing a series of blog posts about The Work Project, her current project on the future of work. They’re online at the Medium page of UCL’s Institute of Innovation and Public Purpose. I’m going to concentrate on the first one here because it comes with a set of interesting notes on why we need to think about the future of work at the moment.

Cottam’s research method tends to be based on participation and dialogue. For this project she’s running a series of workshops at five locations across the country—around 200 people have taken part.

Her starting point:

I have spent decades working on the redesign of welfare systems. These systems have an assumption at their heart: good work. It is presumed that welfare systems will support us if we get into trouble and that these same systems, in the form of education, will prepare us for work, but that most of what we need — the foundational things — will come from decently paid, predictable work. What happens when the foundation stone — decent work — slips away? This is today’s reality.

The ICT/digital wave is transforming economies, and technology use is also connected to the ecological crisis. (Apparently the carbon cost of Ronaldo posting an Instagram photo to his close to 200 million followers is 30 megawatt hours—enough to power three US households for a year, a stat I hadn’t seen before.)

And we’re also more aware of the patterns of injustice, going back to the slave trade, that still sit beneath the way our economies are structure:

And below all this the steady thrum of injustice, the complex legacies of previous revolutions that created wealth for some through the exploitation of others, bodies that we usually could not/would not see... These legacies go unaddressed even as new forms of exploitation are created today: the iPhone for example made in conditions that make it little more than a dis-embodied slave in your pocket or the care worker that tends to others for derisory wages. These are inequalities of geography, race and gender.

Women are likely to earn less, and Black and Brown women are more likely to earn less “in situations of precarity, danger and often degradation.”

(Beyond the 20th century. ‘Disques’ by Fernand Leger, 1918. Photo Gregory Lejeune, Public Domain.)

Cottam’s article uses all of this as a preamble to talk about five reasons to reimagine work.

1. The 20th century was not the best we can do. Whilst many of those planning, writing and making policy are aiming towards precisely this, millions more are imagining new forms of economy that emphasise co-operation and regeneration as opposed to extraction... This new thinking brings a focus on place, knits together a wider socio-political-economic agenda and implicitly asks new questions about work: what is good work, for who and for what purpose?

2. Good work and good lives are about more than money. Existing notions of good work are narrowly focused on material gain... Today we long for lives rich in connection, capability and multiple forms of abundance: we are what Anne-Marie Slaughter and I have called sapiens integra. This longing we feel to live differently is increasingly backed up by research from fields as diverse as neuro-science, physics, biology and sociology. These intellectual developments show that we are neither selfish nor rationally driven, rather we become who we are in relationship to one another.

3. Challenges of transition. ... Bringing down emissions in the next decade, let alone reaching net zero by 2050 means that much well-paid work will have to cease whilst other occupations that are currently low paid and shunned — care for example, must become core to our new economies. Both the US and UK bear the financial and emotional scars of the last unplanned transition (the deindustrialisation of the 1980s). We need to do it differently this time.

4. Work organisations are struggling... As mass production took hold, workers no longer expected the guilds to protect them and the industrial Trade Unions were born. Thinking again about work, means thinking again about work institutions: about what we need to design now to create today’s change.

The fifth reason is that: Technology revolutions create rupture and opportunity.

The work of Carlota Perez gets a namecheck here—which I wrote about last week. Notably, her perspective that conditions do get better in the second part of each of her long technology surges. But as Cottam notes, these gains are not determined by technology, and aren’t always evenly distributed.

First, there is a hidden underside. The lives of some — in the case of the last revolution, unionised, male workers from the global North — have flourished on the backs of others, creating the injustices I refer to above. Secondly, these gains are not automatic — this is not technological determinism. These gains come about through the hard work of movement building, protest, new alliances, imagination and experimentation.

The workshops she has run put the voices of workers at their heart, meaning people who live by their labour, paid or unpaid. They produced some radical ideas, which she explores in the other posts in the series, but here’s a couple of headlines:

The workshops produced radical new ideas about time...; and about the need rethink care, by which I do not predominantly mean the need to have new care services — although these are vital, but rather the need to rethink the boundaries that have been erected between paid work and all those other activities on which a good life and our survival depend.

To read the full set of posts, go to the IIPS’ Medium Page, and scroll down to the different posts titled ‘The Work Project’. Yeah, I wish there was an easier way. There are posts about time, care, transition, organising, business leaders, and project design.

2: A government systems thinking guide

I missed this when it was published a few weeks ago, but the UK’s Government Office for Science has published a guide to systems thinking for civil servants. It probably deserves a wider audience. I’m just going to discuss the main introduction here, but there’s further pages building on each of the sections here.

The rationale for the guide:

(M)any challenges, such as ‘Levelling Up’, can be difficult to define and understand, and ways of influencing them to improve outcomes are hard to design, evaluate and implement... The success of an intervention often relies on collective action taken across boundaries. No single individual, agency or department can tackle a complex problem alone.

Their definition of systems thinking:

A system is a set of elements or parts interconnected in such a way that they produce their own pattern of behaviour over time. Systems thinking is a framework for seeing the interconnections in a system and a discipline for seeing and understanding the whole system; the ‘structures’ that underlie complex situations.

And the reason a system needs a different approach is also explained:

Complex systems behave in a way that is greater than the sum of their parts – you can’t understand the system just by looking at individual elements, it needs to be studied as a whole. Likewise in complex systems there are underlying patterns – feedback loops – which mean that it becomes difficult to relate cause to effect and actions to consequences.

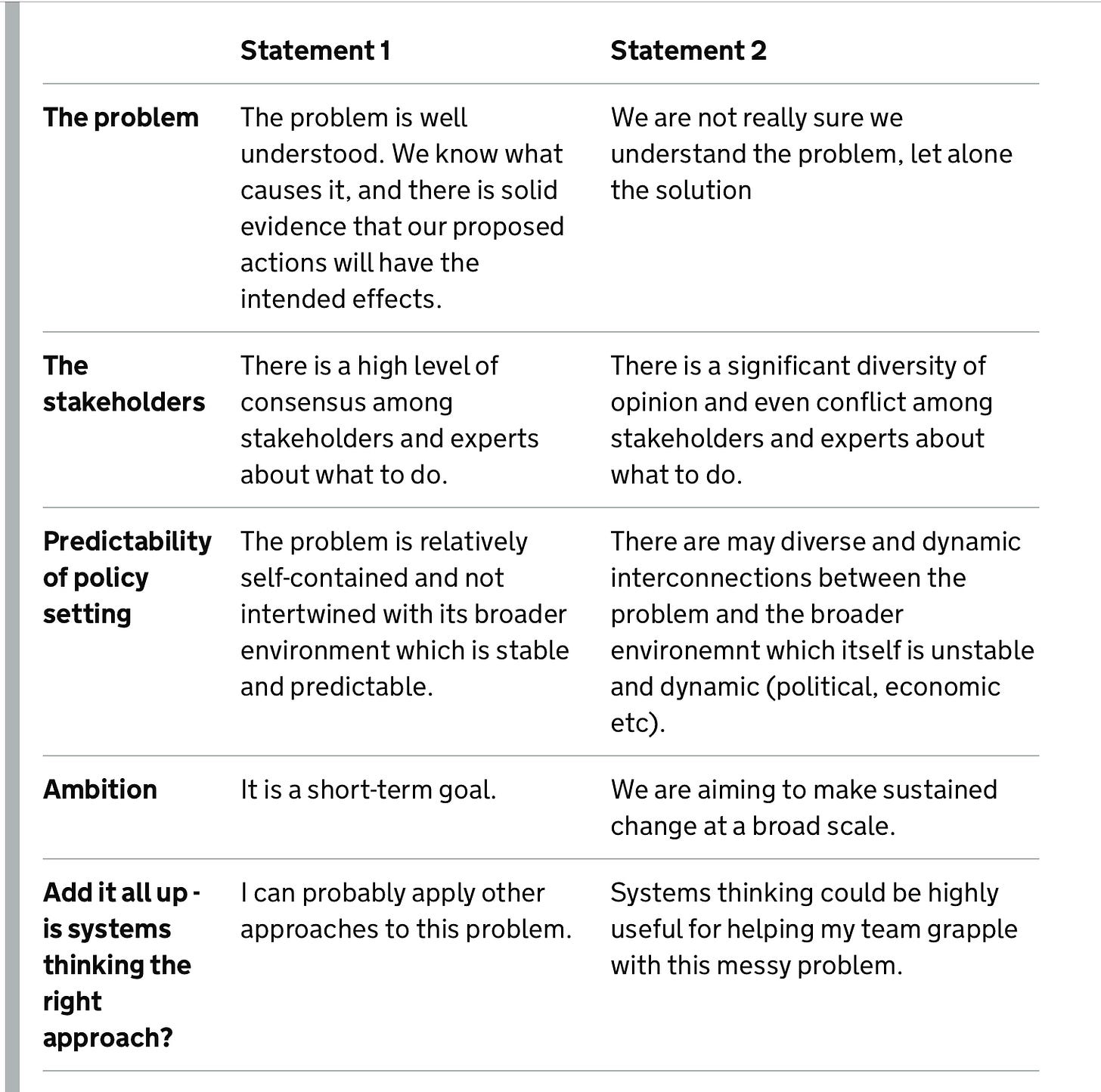

One thing I liked in the guide was the helpful table that helps you to understand whether you needed to approach a problem with a set of systems tools or not. (It has been adapted from work by the Omidyar Group).

(Source: GO Science adapted from the Omidyar Group)

And it also comes with a diagram that helps you see the stages you’re likely to go through in applying systems thinking, together with a summary of the tools that are included in the guide.

I liked the iterative figure of loop between confirming the goal and understanding the system, which is often a place where policy comes unstuck.

(Source: GO Science)

People who have followed the work of GO Science over time will recognise this as a cousin of the Futures Toolkit, which similarly helps civil servants think about futures processes and relevant tools at each stage.

It also comes with a set of case studies.

For the next edition? I’m always puzzled as to why models of Theory of Change are so complicated, especially since unpacking the assumptions that sit behind them is so important to effectiveness, as is clarifying the things that actually make a difference. Maybe Jim Collins’ flywheel helps to clarify thinking here.

And perhaps Three Horizons would also be a handy tool to have in the back pocket to understand systems transitions.

The Leaders’ Quest/Future Stewards booklet published last year ahead of COP26 on 10 Tools For Systems Change to a Zero Carbon World is also a handy companion piece.

Update

Yes, I’m mildly obsessed by four day working weeks, and the burgeoning trials about it. The UK has a large scale pilot running at bthe moment, and one of the participants wrote about her experience to date in The Guardian:

On a personal level, the pilot has been brilliant. All the household chores I used to do at the weekend can now be done on my day off, leaving me more time to spend with my family. As a single mum I have always had to juggle work, school and being a chauffeur for my children, but this new system means that I can be there for my children and enjoy our time together. Furthermore, my performance at work has not been affected at all. I find that I am much more focused on the days I am working.

j2t#342

If you are enjoying Just Two Things, please do send it on to a friend or colleague.