5 October 2021. Housing | Gender

The problem with housing // If women wrote about men the way that men write about women.

Welcome to Just Two Things, which I try to publish daily, five days a week. (For the next few weeks this might be four days a week while I do a course: we’ll see how it goes). Some links may also appear on my blog from time to time. Links to the main articles are in cross-heads as well as the story.

#1: A housing theory of everything (Part 1 of 2)

A guest post by Peter Curry

Do housing shortages cause problems in almost every other field of public life? This is the thesis of Sam Bowman, John Myers and Ben Southwood, who argue in a report called ‘The Housing Theory of Everything’ that housing shortages are at least partly to blame for many of the major problems afflicting western societies, including democratic unrest, inequality, obesity, fertility and climate change.

Quotes below are from this report unless otherwise specified.

Firstly, housing shortages sharply lower productivity and economic growth. As cities grow, they engender growth on almost every metric; income, productivity, pollution, crime, and so on.

According to one study, if just three cities – New York City, San Jose and San Francisco – loosened their rules against building denser housing to the national average level of restrictiveness, millions would move to jobs that made the best use of their skills and total US GDP would be 8.9% higher. This would translate into average American wages being $8,775 higher per year.

House prices in London have increased by an eyeball-popping 2100% over the last forty years. This is 1500% more than wages have increased. These increases have been driven by policy, and that link is most succinctly explained here:

If planning rules are loose then a shock to the path of interest rates has little effect on prices: builders just build more to accommodate demand. House prices didn't fluctuate with interest rate trends before British planning rules became much stricter with the 1947 Town and Country Planning Act, and they don't fluctuate much in Houston or Japan, countries with much more liberal regulation on construction. But since we made building hard to do, we've seen large swings in UK house prices with market conditions and rates.

(Photo of Camden Bus Estate Agents by Chris Sampson via Wikipedia, CC BY 2.0).

It’s worth developing this idea. The housing market is thus linked to the real risk-free interest rate, because housing is turned into an asset. A post on the Bank of England research blog, Bank Underground, extends this point to argue that house price increases over the last forty years are actually due to the fall of the 10 year index-linked yield from 3.5% to -2%.

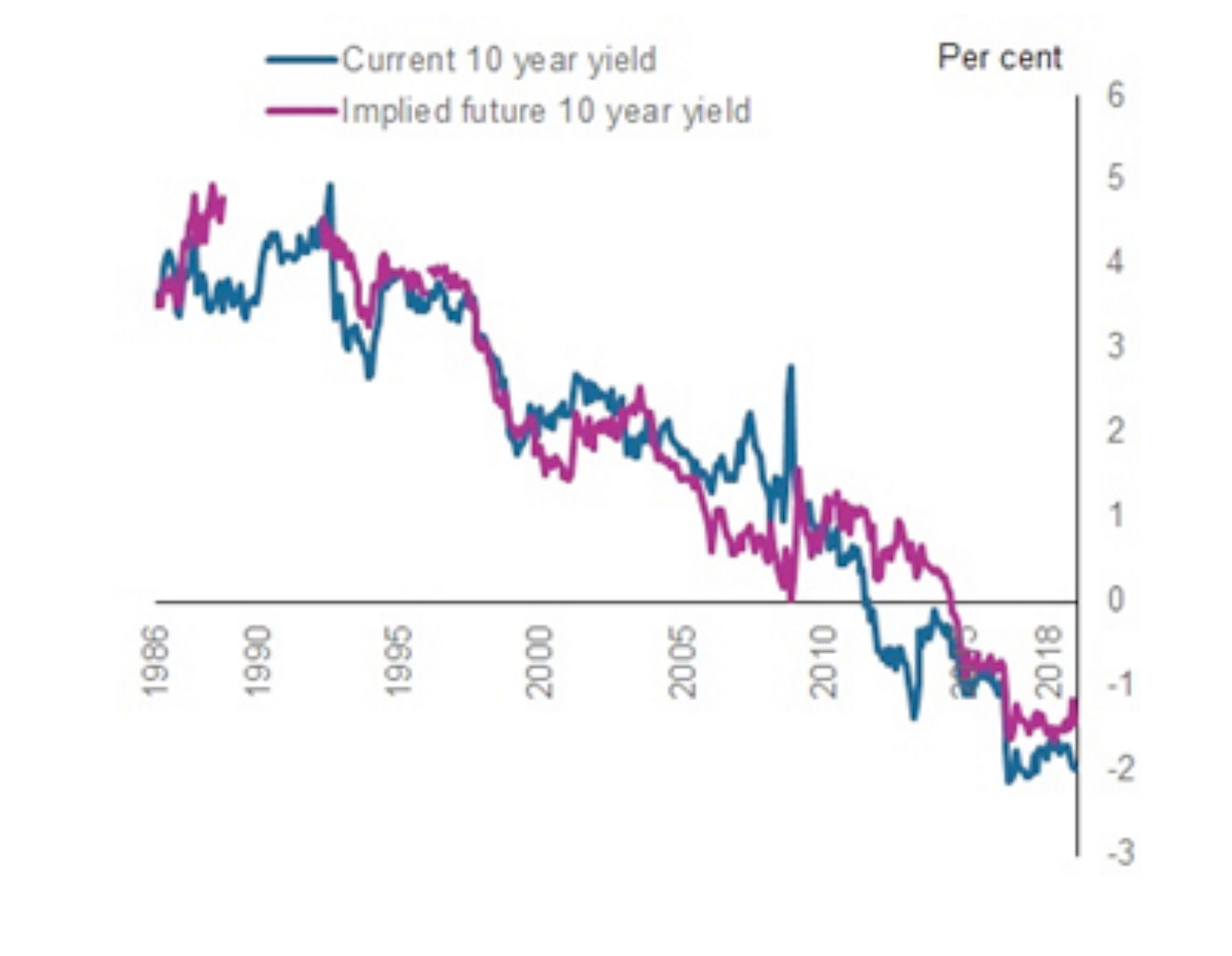

The unexpected collapse (the graph below compares expected and actual interest rates) in the interest rate makes housing a much more attractive asset by comparison, and since you can’t increase the housing stock to capitalise on this demand, prices have shot up.

(Source: Bank Underground)

But the reverse reveals an important caveat:

Our model estimates that an unexpected, but persistent, 1 percentage point increase in the risk-free rate could reduce real house prices by 18% in the long-run. If the risk-free rate were to now increase from its end-2018 level (around -2%) to 0% (levels last seen in 2011), real house prices could fall by 31%.

Nonetheless, the effects of high house prices in the present are problematic. They create divisions, and the most obvious division is between landowners and those who have to rent or mortgage. The latter group ends up paying a disproportionate amount of their income on housing and rent, and leaving them with less money to spend on other things.

One of the fundamental problems is that the exorbitant increases in housing costs means that people who perform lower paid jobs, such as cleaners or service workers, are priced out of cities. But people with significant education or training are still able to move into cities. This skims expertise and skills from other areas of a country, increasing internal disparities of wealth and income.

Typically in the past, that first group would also move to the city, and would gain a wage premium through doing so. This would last even if they moved away.

#2: If women wrote about men the way that men write about women

There was a sharp tweet last week from the writer Charlotte Mendelson:

It produced a host of funny, and well-written replies. (Before you ask, I don’t think she’s answered her own question yet, at least at time of writing.)

One of the replies had a link to an article in MacSweeney’s, by Meg Elison, which addressed the same question with some examples. I’m just going to quote a couple here:

Brett pulled his tank top up over his head and stared at himself in the full-length mirror. He pushed down his jeans, then his boxers, and imagined the moment when Jennifer saw him nude for the first time. His feet were average-sized, and there was hair on his toes that he should probably take care of before tonight. He liked his legs just fine, but his thighs were wide and embarrassingly muscular. He tried standing at an angle, a twist at his waist. Some improvement. In that position, it was easier to see his ass and notice that it was not as pert as it had been at 22. He clenched both cheeks, hoping that tightened its look.

There’s seven or eight examples of similar reverse-gendered writing. The last one is the most explicit, but it’s probably not safe for work. But I also liked this play on the dopy student struggling with something that’s clearly supposed to be the distaff version of Lolita:

Prof. Redgrave looked down to find Stephen gazing up adoringly at her. She blinked down at him, unimpressed.

“But what is Nabikova trying to tell us with this transgressive tale? Is it really just elevated pornography? Or is there a deeper meaning to this titillating tale of a middle-aged woman seducing her teenage stepson?”

Stephen’s look didn’t waver. Redgrave knew there wasn’t a single original thought in the little tart’s head. She had seen the way he lounged, long in his desk, inviting the girls in class to look at him and then crying foul when they prefaced their arguments with a harmless little ‘sweetheart.’ She had graded his papers, marking them down for their puerile assertions and childish leaps of logic.

j2t#180

If you are enjoying Just Two Things, please do send it on to a friend or colleague.