4 November 2022. Brazil | Poetry

Brazil’s agribusiness and the fate of the Amazon.// ‘The Wasteland’, a hundred years on.

Welcome to Just Two Things, which I try to publish three days a week. Some links may also appear on my blog from time to time. Links to the main articles are in cross-heads as well as the story. A reminder that if you don’t see Just Two Things in your inbox, it might have been routed to your spam filter. Comments are open. Have a good weekend.

1: Brazil’s agribusiness and the fate of the Amazon

The best news of the week of course, from the point of the planet, was Lula’s victory over Bolsonaro in the Brazilian Presidential election. Lula and his close supporters immediately talked about the need to protect the Amazon from deforestation.

Vox published a striking chart showing Lula’s record on this the last time he was President.

(Source: Vox)

And there’s a striking passage in the Vox article, by way of a reminder of Bolsonaro’s record on the Amazon:

The right-wing leader stripped enforcement measures, cut spending for science and environmental agencies, fired environmental experts, and pushed to weaken Indigenous land rights, among other activities largely in support of the agribusiness industry. (A representative of the Brazilian government told Vox in September that it’s fully committed to reducing deforestation in the Amazon and is working to that end.)

The science here is fairly scary: About 17% of the rainforest area has been lost:

Scientists estimate that if that number reaches 20 to 25 percent, parts of the tropical ecosystem could dry out, further accelerating forest loss and threatening the millions of people and animals that depend on it.

Contrary to some expectations, Bolsonaro appears to have accepted the result of the election, even if he’s not said as much in public. But The Guardian reported that he’d told members of the Supreme Court, “It’s over”.

And he also intervened to tell the truckers blocking roads in protest against the election result—with Trumpian noises about the election having been stolen—to bring their protest to an end. What I’m willing to draw from this is that the risk of an immediate political crisis in Brazil is averted. One of the reasons for this might be that the military seems no longer willing to intervene directly in Brazilian politics.

A useful article on Social Europe by Camila Villard Duran pulls out the strands that connect the fate of the Amazon with Brazil’s agribusiness sector and with Bolsonarism, if indeed that is a thing.

Agribusiness is vast sector in Brazil, and dominates several of Brazil’s states. It accounts for a quarter of the national economy and—in the first half of 2022–almost half of Brazil’s exports.

(I)ts geographical reach is vast, covering much of the north above São Paulo, a significant swath of the southern states, two powerful central-west states, Mato Grosso and Mato Grosso do Sul, and Roraima in the north. Most of the income gains in Brazil during Bolsonaro’s presidency went to these regions, as agricultural benefited from a devalued national currency and high international commodity prices. The rest of Brazil was not so lucky.

And even without Bolsonaro in the Presidency, agribusiness interests have extensive political representation:

In 2021, members of the Parliamentary Agricultural Front (FPA)—Brazil’s powerful ‘ rural bench’— comprised 46 per cent of the Chamber of Deputies and 48 per cent of the Senate... Under both Bolsonaro and his predecessor, Michel Temer, the FPA promoted its interests, in an organised and systematic way, especially by contesting indigenous territorial rights to legitimise the use of native lands for agricultural production. The FPA also helped articulate proposals and amendments on a range of regulatory issues.

There’s more in the same vein, but the underlying narrative here is that much of the deforestation of the Amazon has been promoted by senior politicians under Bolsonaro who were closely connected to the FPA and are still influential in Brazilian politics.

Duran argues that this isn’t just a matter of political influence. The idea of the land and the countryside goes deep into Brazil’s national identity:

From rodeos and vaquejadas (a sport involving two cowboys on horseback driving a bull into a goal) to country music and festivals, rural cultural traditions are as popular in some areas as football and carnival. Agribusiness uses such activities as opportunities to advance the narrative that it is central to Brazilian identity.

She notes that many of Brazil’s leading country singers backed Bolsonaro.

The deeper point here, apart from the continuing political strength of the FPA, is that much of Lula’s political agenda—even the more centrist 2022 version—runs directly counter to the interests of agribusiness. And that includes protecting the Amazon.

2: The Wasteland

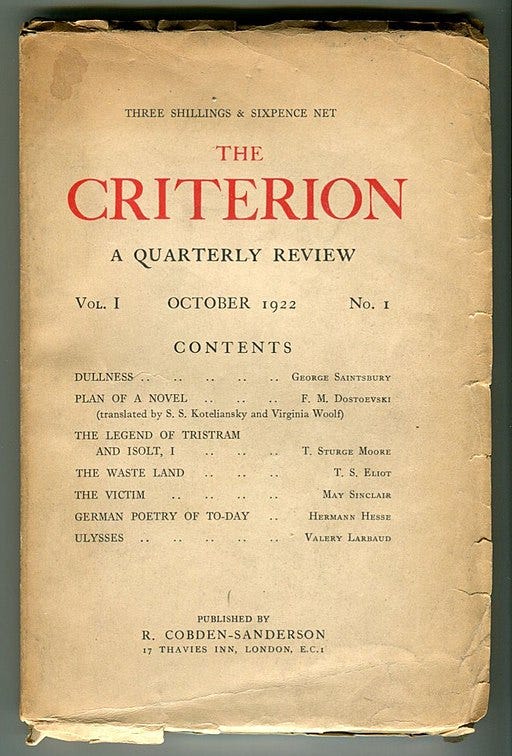

I came late to T.S Eliot’s poem ‘The Wasteland’, which celebrated last month the centenary of its publication in The Criterion magazine in October 1922. Along with James Joyce’s Ulysses, also published in 1922, the poem marked the invention of literary modernism.

(The cover of The Criterion. Image by Andmacro, via Wikimedia, CC BY-SA 4.0)

By late I mean that I read it as a teenager and was, frankly, baffled by it. When I came back to it, it was through an iPad app that contained both an annotated version of the poem and also readings, notably by Fiona Shaw. (This has been updated this year and also released in an iPhone edition.)

The best centenary article I read was by the film critic of the New Yorker, Anthony Lane, who has clearly spent much of his adult life studying the poem. His piece notes the flurry of books and performances that have marked the centenary, and comes to rest on Matthew Hollis’ The Wasteland: Biography of a Poem, due out next month.

Hollis delves into the deep background from which “The Waste Land” arose: Eliot’s childhood in Missouri, as the scion of an uncomfortably distinguished Unitarian clan; summers on the coast of Massachusetts; his Harvard education; his fleeing to Paris and London; his marriage to a young Englishwoman whom he scarcely knew, Vivienne Haigh-Wood, in 1915; the incurable horror of that union, rich in sickness on both sides; his fruitful friendship with Ezra Pound, without whose reshaping “The Waste Land” would not have flourished as it did; and the books on which Eliot fed.

But as Lane notes, there was no fanfare when the poem came out. Eliot, as it happened, edited The Criterion, and this was its first edition. ‘The Wasteland’, all 433 lines of it, came with no preface, preamble, author’s note, introduction. Lane tries to take us back to the moment that a 1922 reader might have stumbled across the poem.

It appeared at first glance to be a poem, but of a disconcerting kind, and further glancing didn’t really help. Parts of it didn’t look, or sound, or feel, like poetry at all:

O the moon shone bright on Mrs. Porter

And on her daughter

They wash their feet in soda water

Et O ces voix d’enfants, chantant dans la coupole!Twit twit twit

Jug jug jug jug jug jug

So rudely forc’d.

Tereu

As Lane says, there’s a jumble of references here: a line from Wagner’s Parsifal, something from a music hall song, maybe, a smutty Elizabethan reference. Eliot has an austere image, but his sense of humour was never far below the surface. Lane quotes the poet’s response to a questionnaire sent out to poets earlier in 1922:

“Do you think that poetry is a necessity to modern man?” Eliot: “No.” “What in modern life is the particular function of poetry as distinguished from other kinds of literature?” Eliot: “Takes up less space.”

In 2022, what might a new reader make of it?:

If you are an ordinary reader now, in 2022, with no classical education, no French, and no access to opera, what happens when, by chance, you pick up a book and stumble upon this same passage? What is your first response? A snort of laughter, I presume, along with a suspicion that this guy Eliot (whoever he is) must be taking you for a ride. If pressed, you might describe the lines as starting off like a nursery rhyme and then collapsing into nonsense.

Lane suggests that Eliot would prefer the uneducated reader to the informed:

“Genuine poetry can communicate before it is understood,” he wrote, in an essay on Dante. “It is better to be spurred to acquire scholarship because you enjoy the poetry, than to suppose that you enjoy the poetry because you have acquired the scholarship.”

It’s a long, long piece, and does serve as a valuable introduction to the poem. Even the most casual reader will notice that it’s drenched in loss. The millions who died in the European war and from the Spanish flu peer out between the lines, even as those who are still living try to make sense of their continuing. At one level, like much other art of the 1920s, it is a howl of post-traumatic stress disorder.

But it also has a filmic sense to it—the energy is in the rapid cuts from scene to scene, from character to character, scanning the city, an ensemble piece. Early Robert Altman, perhaps. This is one of the reasons that listening to the poem brings it to life; it is easier to hear the story and see the pictures.

And perhaps this cinematic eye is also a reminder that literature came late to modernism. By the time Eliot wrote ‘The Wasteland’, or Joyce Ulysses, Picasso, Stravinsky and others had spent well over a decade dragging art and music to this new sensibility.

Lane suggests that for a century old poem, ‘The Wasteland’ is still surprisingly fresh.

All of which, for some people, will be about as thrilling as a dead bouquet, left over from last Tuesday. Why such a fuss over an old poem?... One answer is that the new, in every field, flowers out of the old; the radical, by definition, has roots. What’s more, Eliot has the knack of sounding newer than the new. Another answer is that there’s no choice in the matter, because the poem has already entered the language... You may not know “The Waste Land,” and you may not like it if you do. But it knows you.

‘The Wasteland’ grew in reputation and influence across the rest of the 20th century. An Evelyn Waugh character nods in its direction; Francis Bacon works through an obsession with the poem in a 1971 triptych; Dylan dabbles with the start of a reading; the cartoonist Martin Rowson reworks the poem as a graphic noir novel. In some ways, the poem is everywhere now, even if you have never opened it. April is the cruellest month.

Another reason that listening to ‘The Wasteland’ works as a way into it is that it brings the language alive, it takes it off the page, and maybe reduces the obstacles from the chunks of other languages that pepper the poem. The BBC’s Poetry Please ran a version which intercut three different versions—including T.S. Eliot’s reading—which is still available to readers in Britain on the iPlayer, or elsewhere via a VPN, I guess. There’s a YouTube version in a similar conversational vein that features Jeremy Irons and Eileen Atkins.

And there are also some interesting resources at the British Library’s website.

Update

The chart on the increasing connectivity in the world economy between 2000 and 2017, which I shared earlier this week, came from a long synoptic post by Noah Smith arguing that “the system of the world” was coming to an end, with the US and China decoupling their economies. A brief extract:

The key thing to understand about this decoupling, I think, and the reason it’s for real, is that this is something the leaders of both the U.S. and China want. No matter what you heard in 2018, this is not a case of a protectionist U.S. trying to defend its manufacturing industries while China becomes the champion of globalism. The U.S. is acting not out of concern for its industries — indeed, its chip industry will take a huge hit from export controls — but because of how it perceives its own national security. And China’s leaders want to shift to indigenous industry, regulated industry, and even nationalized industry, even if that shift makes China grow more slowly.

j2t#389

If you are enjoying Just Two Things, please do send it on to a friend or colleague.