4 March 2024. Optimism | Alcohol

Finding ways to be optimistic in the face of climate change // Most of the things we know about alcohol are wrong. [#548]

Welcome to Just Two Things, which I try to publish three days a week. Some links may also appear on my blog from time to time. Links to the main articles are in cross-heads as well as the story. A reminder that if you don’t see Just Two Things in your inbox, it might have been routed to your spam filter. Comments are open.

1: Finding ways to be optimistic in the face of climate change

The science fiction writer and futurist Karl Schroeder has a long post on his newsletter about how we construct enough optimism to be able to act in the face of all of the dismal data and experience of both climate change and our collapsing biodiversity. The piece is literally subtitled, “Overcoming despair in the Anthropocene”.

He starts with a quote from a recent post of his that I’d meant to discuss here:

“At some level, we recognize that we’re working to build a future we no longer believe in. It’s our parents’ future, it’s not ours.”

This old future (a “used future”, as futurists might say) is a future that orbits around ideas like “Progress”. Regular readers will know that one of the recurring discussions I have here is about “the end of modernity”, a set of ideas that have notions of “progress” at their heart. Here’s Karl Schroeder’s take on this:

Global warming, and its symptom of climate change have rendered the aspirational futures of the previous generations impossible. Imperceptibly, our civilization has shifted from one that was running toward a bright future, to one that is running away from a dark one... There are no realistic visions of the near future in which Earth’s ecological crises do not get worse.

Schroeder started writing his newsletter partly because he was worried that we were insufficiently alarmed by the threat that humankind posed to other species, and of course these are in sharp decline because of us.

So, if you want to be optimistic about our future, you probably have to lie to yourself, or you need to find ways to face up to these truths.

(Walter Benjamin in 1928. Public domain via Wikimedia.)

Schroeder reminds us of Walter Benjamin’s ‘Angel of History’, conjured by Benjamin in the middle of the 20th century when optimism was similarly difficult. (The text here is by Benjamin):

His face is turned toward the past. Where we perceive a chain of events, he sees one single catastrophe which keeps piling wreckage upon wreckage and hurls it in front of his feet. The angel would like to stay, awaken the dead, and make whole what has been smashed. But a storm is blowing from Paradise; it has got caught in his wings with such violence that the angel can no longer close them.

Benjamin’s storm was the notion of Progress. Schroeder’s is Global Warming. I’d say that these are basically the same thing right now: to adapt a phrase from a recent post about AI, capitalism is choking—more or less literally—on its own exhaust.

The other related issue is what he calls “disenchantment”, caused by “the theft of divinity from our experience of the natural world.” There’s a whole cultural history, of the invention of the notion of the “sublime”, but it’s another problem of modernity:

If people no longer believe in God, they still can’t turn to nature to find the divine, because for Western culture nature is by definition the opposite of divinity; it’s the realm of stupid coincidence and blind causality,

What this all means is that if we are to construct an optimistic view of the future, we can’t do it by restarting “progress”. The train has gone:

It’s too late to put Progress back on track. Progress is not our younger generations’ lived experience... We can’t achieve genuine optimism by avoiding the nihilistic horror of this extinction event; instead, we have to confront it head-on. We have to find a way to become the Angel of History yet still look forward to the future.

(emphasis in the original)

The rest of the article, which I’m probably not going to do justice to here, is about a strategy that attempts to make this possible, drawing on futures methods such as speculative design— to create

a safe space where we can play with ideas that we might not be able to rationally defend.

The starting point in this—which he is playing with as an exercise, as a thought experiment—is to “double down on meaninglessness”. For the moment, let’s just say that this means assuming that natural selection is random, not part of a Grand Design or a Hidden Hand.

The second point is about dealing with disenchantment. Schroeder quotes the 21st century philosopher Jane Bennett, who

counters the prevailing narrative of disenchantment with numerous examples of people finding the divine in the ordinary drudgery of human life, in our technologies, and in nature too, even on a planet that’s become just ‘a yard.’

Bennett says that we are in love with both the human and the non-human, despite everything. And Schroeder identifies reasons why this might be so:

life’s complexity is entirely unnecessary and the peacock’s tail is a useless extravagance to everybody but the peahen. Yet magnificent antlers, brilliant wing patterns, fluorescent skin colours, bioluminescence, bizarre shapes and sizes, and all the bewildering frills and adornments that living beings come up with, don’t have to have a reason.

So in the spirit of speculative futures, of taking an idea to disrupt the normal, of playing with it up to open up thinking, Schroeder proposes, in the service of finding sources of optimism that can also survive the glare of Benjamin’s Angel, a prototype idea called ‘Adornment Theory’:

the myriad adornments and extravagances of life have no objective purpose (but) AT goes on to say that they nonetheless are pride embodied as active subjects in the world. The peacock is proud of his tail; we humans are proud of our intelligence and technology... Life can be extravagant; it can create beauty. So it does.

And in this spirit, although Earth does not need life to make its systems work, there is life on earth.

(An angel in Rome. Photo: Ashu Shah/flickr. CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.)

From the perspective of the Angel, it sees a catastrophe because it keeps looking back at the wreckage, looking at what’s been lost, not looking ahead at what can still be born.

The ethics of adornment say humanity is part of this creativity and always has been, and we are uniquely positioned to encourage and empower it even further. That’s it... It replaces those negative motivations, which may be temporarily effective but will poison us in the long run, with a single, positive goal: to promote the diversity and overflowing generosity of Earthly life. It’s a stance that doesn’t force us to start with what we've lost, indeed with what we ourselves destroyed. Like life itself, it faces only the future.

There’s more here, but Schroeder summarises the design principles of what he’s talking about like this: (1), Design that inspires people to think in new ways; (2), Reframing problems so design thinking can do its work; (3), Posthumanism—in which humans are just another species; (4), Earned optimism; and (5), Looking to the present for answers, not the past.

--

The article also comes with a helpful booklist on dealing with disenchantment:

Ursula Goodenough, The Sacred Depths of Nature

Timothy Morton, Ecology without Nature

Donna J. Haraway, Staying with the Trouble

Stuart A. Kauffman, Reinventing the Sacred

2: Many of the things we know about alcohol are wrong

One of the more famous charts about drugs use was published by David Nutt in The Lancet in 2010. This was shortly after he had been dismissed from his role as the chair of the UK’s Advisory Council on the Misuse of Drugs for saying things about drugs harms that politicians didn’t like.

(Source: "Drug harms in the UK", by David Nutt et al. The Lancet)

Anyway, the chart says that when you take all harms into account, alcohol is the most harmful drug; when you take into account only direct harms it sits fourth, behind heroin, crack cocaine, and metlamfetamine. The explanation of the methodology is here.

Which is a slightly long way into an article in BBC Futures on the impact of alcohol on young adult brains that suggests that most of our assumptions about the effects of alcohol are wrong, and not in a good way. By “young” they mean brains in people up to the age of 25.

The author of the article, David Robson, says that he wishes he’d known more about this science when he was younger:

If I'd heard what I now know about the unique ways that alcohol can affect the young adult brain, I might have been a bit more cautious. At 18, my brain was still metamorphosing , and would not reach maturity for at least seven years.

Recent research also suggests that the continental European drinking habits are necessarily better for you than those in the UK, and that some familiar assumptions about introducing young people to alcohol gently at home are wrong as well.

The first thing to say—as the chart shows—is that alcohol is a toxin. It can cause cancer:

Even small quantities can be carcinogenic, leading the World Health Organization to declare that "when it comes to alcohol consumption, there is no safe amount that does not affect health".

But as societies we have been using alcohol for a long time, and so our social and legal policies around alcohol are broadly about harm reduction. Health guidelines in countries where alcohol is a social norm tend to follow the same lines as the US: “no more than two drinks a day for men, and no more than one drink a day for women”.

However, in young adults, the effects of alcohol are more pronounced, for a number of reasons. One is that they have less bulk than older adults, so there is less body to absorb it. Another is young adults have a higher “head-to-body” ratio, so alcohol gets to the brain faster, and in larger quantities, as Ruud Rodbeen of Maastricht University explains:

Within five minutes , it reaches your brain, easily crossing the blood-brain-barrier that generally protects your brain from harmful substances. "A relatively large part of the alcohol ends up in the brains of young people, and that is yet another reason why young people are more likely to get alcohol poisoning," Roodbeen says.

Newer neuroscience research also suggests that brains going on developing for far longer than we used to thought—meaning that they are still developing as people get to be of an age where drinking is legal and acceptable.

"A lot of people describe the adolescent brain as having a fully developed gas pedal without brakes," says (Lindsay Squeglia of the Medical University of South Carolina). And bathing our neurons in alcohol – which is known to release inhibition – may only amplify this thrill chasing.

Too much alcohol — in terms of volume and frequency — can also impair the brain’s long-term development:

Longitudinal studies show that early drinking is associated with a more rapid decline in grey matter, while the growth of the white matter is stunted. "Those super-highways aren't getting paved as much in kids who start drinking," says Squeglia.

That may not show up in tests straightaway—young brains can also work harder to fill in gaps. But you see it eventually.

Drinking alcohol in these years—or not—also seems to have a relationship with the development—or not—or the genes that associated with alcoholism. The longer that someone delays drinking alcohol, the less likely it is that these genes come into play.

And this plays out in a finding that says that parents who allow adolescents to drink small amounts at home—at meals, for example, to learn about drinking in a safe environment—may not be doing them any favours:

"The research has shown that the more permissive a parent is with alcohol use, the more likely a kid is to have problems with alcohol later in life," says Squeglia. A comprehensive review suggests that contrary to the forbidden-fruit belief, "parents imposing strict rules related to adolescent alcohol use is overwhelmingly associated with less drinking and fewer alcohol-related risky behaviors".

The research also suggests that later legal ages for buying alcohol have a beneficial effect. Alexander Ahammer at the Johannes Kepler University Linz in Austria did a study that looked at drinking behaviour in Austria (where the legal age is 16) and the US (21):

Both countries see an increase in binge drinking after someone has passed the minimum age. "But this jump was 25% higher in Austria at 16 than in USA at 21," Ahammer says. Waiting, in other words, seemed to have encouraged more responsible behaviour when Americans were permitted to purchase drinks legally.

The legal drinking age, says Ahammer, is seen as a signal that drinking is safe.

Finally the idea that moderate drinking is better for you isn’t borne out by health risks:

According to the World Health Organization, data indicates that half of all alcohol-attributable cancers in the European region are caused by light and moderate alcohol consumption.

This does at least bear out one of the best one-liners I heard about the effects of alcohol: The French drink slowly and kill themselves; the Scots drink quickly and kill each other.

Obviously the evidence-based policy here would be to restrict drinking age to above 25. This seems unlikely to happen, because alcohol consumption is so socially embedded. And it causes problems when other markers of adulthood happen at 18 (voting age, for example).

But young people seem to be getting there without legal restrictions. In the UK certainly, there are clear trends that young people are starting to drink at an older age, and also drink less often once they start.

Other writing: Music

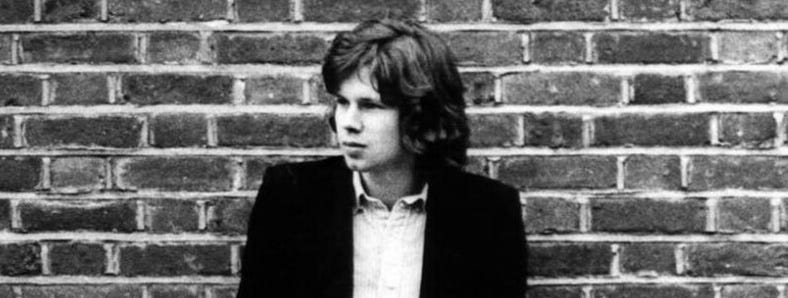

I write about folk music at the modestly-run site Salut! Live and I have done a series of articles on an interview at a recent indoor folk festival with the influential producer Joe Boyd and the engineer John Wood. Boyd produced Fairport Convention and Nick Drake, and others, their most influential records were recorded at John Wood’s Sound Techniques Studio in Chelsea. There are three parts to this set of ‘Tales From the 1960s’: Sandy Denny features quite large in Part One; Fairport Convention in Part Two; Nick Drake in Part Three.

(Nick Drake in 1969. Photo: Keith Morris. Public domain)

j2t#548

If you are enjoying Just Two Things, please do send it on to a friend or colleague.