4 June 2022. Top Gun | Jubilees

Top Gun: Maverick and questions of American decline // Royal subjects

Welcome to Just Two Things, which I try to publish daily, five days a week. Some links may also appear on my blog from time to time. Links to the main articles are in cross-heads as well as the story. And a reminder that if you don’t see Just Two Things in your inbox, it might have been routed to your spam filter.

This a a weekend bonus issue because of the British bank holiday. Back on Monday.

1: Top Gun: Maverick and questions of American decline

Spending a long weekend watching the full panoply of a nation in denial about decline made me think about a review by James Crabtree of Top Gun: Maverick in the Financial Times. That’s almost certainly behind the FT paywall, so I’m indebted to John Naughton’s blog both for the pointer to the review and to a link to a pdf of the article.

There is something a little odd about a sequel to a film that is filmed more than 30 years later, and which has several of the same stars in it. Crabtree, a former FT journalist, is now based in Singapore, and detected some geopolitical anxiety in the story.

(Top Gun: Maverick poster via IMPA Awards)

The original Top Gun, of course, came out just as America’s post-war power reached its peak:

The original Top Gun, released in 1986, was both a box-office smash and a Reagan-era hymn to American aerial and naval might. Directed by Tony Scott, it became both the highest-grossing movie of that year and at the time among the highest in history... Top Gun also arrived at a moment of rising American global supremacy, giving it particular geopolitical poignancy. The film topped movie charts the year after Mikhail Gorbachev became general secretary of the Communist party of the Soviet Union, and as the balance between the two superpowers shifted decisively in America’s favour.

In comparison, says Crabtree, Maverick is “a rather anxious kind of blockbuster”, perhaps even “an elegy for relative American decline”.

A not yet greying Cruise, now 59, returns with his sunglasses, motorbike, and bomber jacket to teach pilots at the Navy’s elite flying school, yet is still only a Captain, a problem the film’s script addresses head-on. Val Kilmer also re-appears, but he has been promoted; he’s now an Admiral, if one “in the last throes of his life.”

Crabtree saw the film at its premiere in Singapore. There were members of the US Navy in the audience, and the American Ambassador, Jonathan Kaplan gave a speech beforehand about how

many thousands of US sailors and naval pilots work throughout that region... to “ensure peace, security and a free and open Indo-Pacific”.

But the sequel seems to undermine this idea, as Crabtree observes:

The film’s opening sequence features Rear Admiral Chester “Hammer” Cain, played with gravelly élan by (Ed) Harris. Dubbed “the drone Ranger”, Cain wants to replace ace pilots with autonomous air-strike capabilities powered by artificial intelligence. “The future is coming,” he tartly puts it to Maverick. “And you’re not in it.”

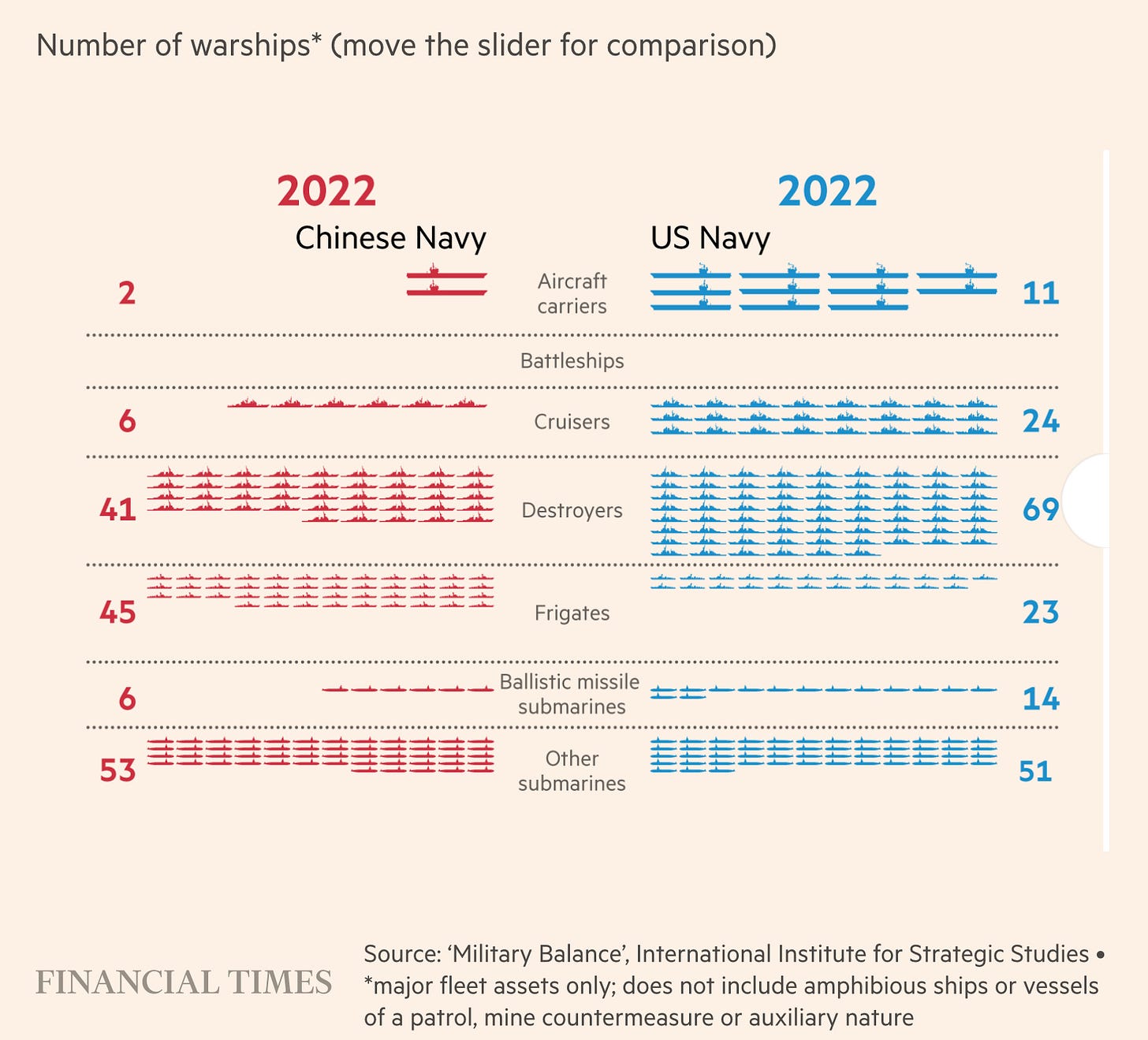

That’s not completely true. In practice, American defence strategy is moving away from the counter-terrorism disasters of the last two decades and back towards great power competition: aircraft carriers and planes do matter. But the US is no longer the undisputed master of this landscape. The FT version of the article on their app comes with a neat slider which shows the growth in Chinese naval power, and the decline of American, in the years between the two films.

“We should welcome the return of Top Gun, because it is a vision of what we actually need in US defence,” explains (Elbridge Colby, who helped to write the influential 2018 National Defense Strategy). “War movies in the 2010s were all set on Afghan hilltops or the streets of Baghdad. But we are now in an era where the US must invest in new technology, but where we also need to be sending more aircraft carriers and planes to the Indo-Pacific to help deter a rising China.”

Not, of course, that the C-word is mentioned anywhere in the movie. Hollywood is sensitive to offending sensibilities in one of its biggest markets.

But Cruise and his pilots are pitted against so called “fifth generation” planes, developed over the last decade. China is one of the relatively small number of countries that has such planes, and they are deployed over the South China Sea, one of the likely flashpoints between the USA and China.

These little puzzles prompted Max Read’s Read Max newsletter to speculate about who the enemy in Top Gun: Maverick might be.

While the bad guys in the original Top Gun displayed some recognizable geographical and visual markers — aviators fly Russian planes (fictional MiG-28s) with Chinese markings in the Indian Ocean — the “rogue state” targeted by the naval aviators in Top Gun: Maverick is almost fully generic.

All the same, there are some clues in the film:

We are told that The Enemy is a rogue state seeking to enrich uranium. We know it has “fifth-generation” fighters, which means it either has a sophisticated and well-resourced military-industrial apparatus, or is quite friendly with a power that does. We know it has mountainous terrain and a coast. And we know that it has a supply of F-14 Tomcats, the classic (fourth-generation) American fighter jet that Maverick and Goose fly in the original Top Gun.

China can therefore be ruled out: it has no F-14s. North Korea has no fifth-generation fighters and no F-14s. Russia is more promising, but probably wasn’t a rogue state when the film was made, and taking out a Russian nuclear facility would still leave plenty more. His preferred candidate is Iran.

But—in keeping with James Crabtree’s sense that the film is about decline—Read has a more radical suggestion: the enemy in the film is “death itself”.

the thing that sets it apart most clearly from the original Top Gun, is its ghostly, elegiac tone.

Read points to a couple more articles that go deeper into this psychological landscape. In Vulture Alison Willmore suggests that the whole film is a “death dream” following a crash early on. Her colleague Bilge Ebiri says that in the film Cruise “seems constantly poised on the edge of death”:

The reality these pilots inhabit is a curiously empty one, mostly devoid of civilians, and the vast stretches of flat desert across which their jets blast feel like a dreamscape — an effect enhanced by the fact that during their training exercises, the valleys and mountains and missiles and enemy fighters they must evade exist only as readouts on computer screens... Never have fighters zooming across the screen looked so thrilling and felt so resoundingly, so gorgeously sad.

And on this reading, Cruise becomes a metaphor for America itself:

(T)he movie’s sepulchral qualities can also be read as an expression of anxiety over the future of the American imperial project. It’s not simply as The Enemy, as described, doesn’t exist in the real world. It’s that it cannot exist. No country can feasibly threaten American military hegemony. The only thing we have to fear is our own decline.

Incidentally, a footnote to Max Read’s piece also admires the dexterity with which the film’s scriptwriters have managed to create a more or less credible enemy for the Top Gun pilots:

The work that Top Gun: Maverick’s script does to create an enemy that is threatening to American military prowess, but not too threatening, is magnificent. The Enemy is a pariah state (it’s weak)! But it has fifth-generation fighters (it’s strong)! But we could beat those fighters with F-35s (it’s weak)! But we can’t use the F-35s due to the elaborate video-game level The Enemy has built around its urianium enrichment facility (it’s strong)!

Don’t try this at home. The trailer is here:

2: Royal subjects

The photographer Martin Parr is the poet of the English quotidian, and he has been photographing public celebrations of Royal occasions ever since the Silver Jubilee in 1977.

He’s a member of the Magnum Collective, who posted a short article with a whole set of photographs attached to it, of Royal occasions over the years since then:

Street parties were already a favorite subject, so the Silver Jubilee celebrations were not to be missed, tens of thousands of them springing up and down the land in early Summer. Parr made a few successful images at a party in Todmorden, capturing the modest sense of occasion and mild reverie, families stung along makeshift tables that line the entire length of a road strung with balloons and bunting.

And, as the Magnum piece notes, “royal-themed celebrations and street parties became a happy hunting ground for many years to come.”

(Martin Parr Diamond Jubilee celebrations, Wolverhampton, 2012 © Martin Parr | Magnum Photos)

Updates

Guns: No sooner did I mention Jeff Yang’s piece from a decade ago about regulating American guns in the same way that you regulate cars, than Scientific American popped up with an editorial that recommended pretty much the exact same thing:

In the U.S., we have existing infrastructure that we could easily emulate to make gun use safer: the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration. Created by Congress in 1970, this federal agency is tasked, among other things, with helping us drive a car safely. It gathers data on automobile deaths. It’s the agency that monitors and studies seat belt usage. While we track firearm-related deaths, no such safety-driven agency exists for gun use… While cars have become increasingly safer (it’s one of the auto industry’s main talking points in marketing these days), the gun lobby has thwarted nearly all attempts to make it harder to fire a weapon.

Netflix: Meanwhile, Netflix’ attempts to shore up its revenues by clamping down on sharing passwords seems to be coming unstuck in Peru, which is one of the three countries in Latin America where they are trialling the idea. Rest of World reports that the main result so far is customer confusion:

For the first time, the company is enforcing its policy that a “household” consists exclusively of people a subscriber lives with. The full rollout of the plan came on the heels of an earnings call that saw Netflix’s first drop in overall subscribers since 2011.

The article says that customers are confused by what Netflix means by ‘household’, and the confusion extends to its customer service representatives:

For some, the price increase has been enough to convince them to cancel their Netflix accounts outright. Others continue to share their accounts across households without any notification of the policy change or have ignored the new rule without facing enforcement. Overall, the lack of clarity around how Netflix determines a “household” and inconsistent levying of the new charges on different customers have left subscribers in the trial confused, risking action from consumer regulators.

j2t#323

If you are enjoying Just Two Things, please do send it on to a friend or colleague.