3rd March 2021 | Mars | Poetry

Everyone’s going to Mars; the politics of Amanda Gorman’s Inauguration poem

Welcome to Just Two Things, which I try to publish daily, five days a week. Some links may also appear on my blog from time to time. Links to the main articles are in cross-heads as well as the story.

#1: ‘Everyone’s going to Mars’

Three different probes, sent by three different countries, have landed on Mars. It’s not a coincidence—the timing is driven by the alignment of the planets—but it is still notable. Apart from the American mission, China and the UAE have sent probes.

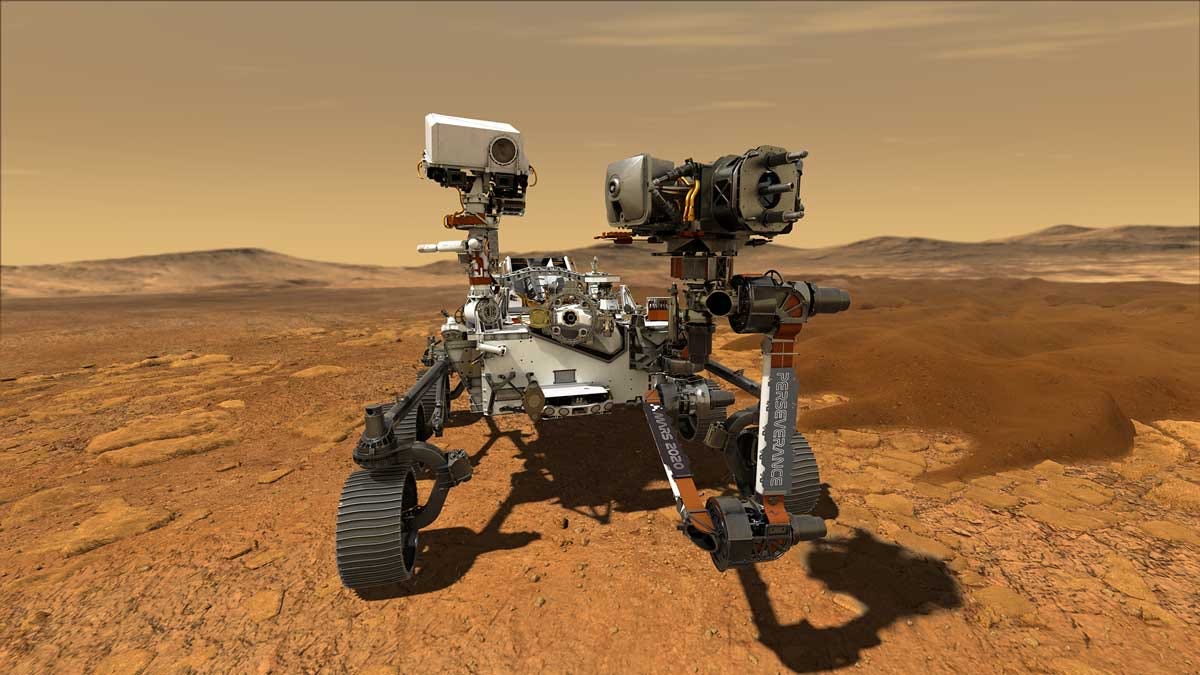

The US craft, Perseverance, is designed to test for what would be needed to land humans on the planet, which would be some kind of culmination of a deep narrative, running at least from H.G.Wells through his near namesake Orson to David Bowie. Via this very early science fiction film.

(Rendered image of Perseverance: NASA)

A piece in South Africa’s Daily Maverick picked up the story:

“Perseverance will be unique in the sense that it will have technology on board to search for ancient microbial life. The other missions so far have only established conditions that are suitable, that Mars might have harboured primitive life in the past. But there were no means of actually exploring that fact, to see whether microbial life ever existed,” says Dr Pieter Kotze, extraordinary professor at the North-West University’s Centre for Space Research.

One can admire the science, but it is hard to talk about Mars these days without noticing that it has become a fixation for those Silicon Valley billionaires who seem to think it’s going to be a solution to the pressing questions of the ‘Grand Problematique’ that we have here on our current planet. Elon Musk is probably the poster child here, although Bezos and Branson are also playing around with space. Musk’s SpaceX corporation explicitly talks about colonising Mars. (Its four minute promotional video is here). If a goal is a dream with a deadline, SpaceX has even set some pretty aggressive deadlines: sending a cargo ship to the planet by next year, humans by 2024.

That’s not going to happen, of course: the launch window only comes round every 26 months, for one thing, and there is a huge range of technological issues still to overcome. But even more cautious observers think we might only be 10-15 years away from a manned flight to the planet. And in the meantime the Off-World project, run by Proudly Human, is conducting a series of extreme habitation experiments on earth to learn about how best to prepare for extreme conditions on the Moon and Mars.

Jim Adams, ex-NASA, compares where we are with space exploration with the early days of global exploration:

“The best way to look at it is, if we were to [compare where we are in terms of space travel] to the days when Europe was dominating the oceans, you know, the Spanish galleons and that sort of thing; we’re still looking at how to build good canoes.”

In the days of decolonisation, this maybe ought to raise some alarm bells. And you don’t have to be Gil Scott-Heron (…”but Whitey’s on the Moon”) to ask questions about the cost and effort of space research and exploration when the problems on our own planet are becoming increasingly existential. That point was made in a video produced to mark the arrival of Perseverance on Mars by America’s Fridays for the Future organisation. I’m not actually sure that this works, though. The SpaceX PR team would have been pretty pleased with almost all of this, and the punchline is so late that if you blink, you miss it.

#2: Decoding Amand Gorman’s Inaugural poem

It’s been more than a month now since America’s Youth Poet Laureate, Amanda Gorman, stole the show at Joe Biden’s Inauguration with her poem, ‘The Hill We Climb’. (The text is here). Two academics, Virginia Jackson and Meredith Martin, have now written an intriguing piece decoding the poem and its contexts.

It’s long, and it’s quite complex, but I took two things away from their article.

The first is that the style of Gorman’s poem brought back into public discourse a whole range of communal forms of poetry—“ballads, odes, elegies, poems for affairs of state, marching songs, anthems, and hymn”—without being any one of them.

Gorman’s poem managed to do what those genres did without obeying their generic protocols. She adhered to the loose rules for an inauguration poem (talk about America, promise redemption, reiterate the word “we”), but her poem hewed closer to longstanding genres of public oratory than it did to earlier kinds of public poetry. Her performance thus successfully evoked the idea of a communal poetry without being any particular genre of communal poetry. This is the idea that made it seem, on social media at least, as if Americans listen to poetry all the time

In other words, one of the reasons for her success was that she plugged into familiar archetypes and rhythms. This reminded me of Umberto Eco’s riff on the success of the film Casablanca —“the archetypes hold a reunion.”

The second observation is that this collection of communal poetry archetypes represents a challenge to an idea of a certain view of poetry promulgated by elite white European critics in the 19th century, notably John Stuart Mill.

Mill famously and influentially wrote almost two hundred years ago that “eloquence is heard, poetry is overheard,” that “eloquence supposes an audience; the peculiarity of poetry appears to us to lie in the poet’s utter unconsciousness of a listener”… By distinguishing between poetry and eloquence, and by not-so-subtly dissing poetry that can be heard, Mill set up a strategy for co-opting anyone’s actual voice by an imagined universal voice.

This critical view detaches poetry from an audience—which is why Jackson and Meredith take issue with it.

By resisting poetry’s politics, thinkers about poetry have rendered the poem as an utterance addressed to an intimate, invisible, implicitly White and male (because unmarked) listener. The reason that listener was imagined as invisible was because visible listeners tend to have their own affiliations, genders, races, anti-races, transgenders, and ideas. By reading for “the speaker,” we forget to read for poetry’s actually populous and visible audiences.

Mills’s argument is also an argument against accessibility, which is why he was writing just at the time that 19th century England exploded in print for the first time, with cheap books and pamphlets everywhere.

There’s much more here, and it’s a rich discussion. The section at the start that locates Gorman’s look at the Inauguration within a whole history of Black American politics and literature is fascinating. There’s some elegant textual analysis.

But of course, at the heart of the story they’re telling is an argument that says that poetry is political, and that the explosion of cheap and shareable media represented by the World Wide Web allows it to reclaim that status. The triumph of Gorman’s poem was that by clothing itself in old forms, it allowed itself to take on a life in 21st century media:

Maybe this is the poetry of the future — a poetry in process and in conversation, and in anticipation of more conversations (of which ours is only one), a poetry embedded, mediated, saturated, circulated, followed, shared. A poetry many of us didn’t know we needed until it just happened.

Updates:

Glenn Lyons has written an extended account of the panel I was on last week on whether the pandemic would improve our chances of reducing carbon emissions.

j2t#043

If you are enjoying Just Two Things, please do send it on to a friend or colleague.