3rd August 2021. Ships | Drugs

The 21st century sailing ship; what psilocybin does, at least to mice

Welcome to Just Two Things, which I try to publish daily, five days a week. Some links may also appear on my blog(https://thenextwavefutures.wordpress.com) from time to time. Links to the main articles are in cross-heads as well as the story.

#1: 21st century sailing ships

Low Tech magazine does what it says on the tin. It looks at low technology solutions to our current systems. A recent article looked at the prospects for 21st century sailing ships, in a sector that is currently an environmental catastrophe.

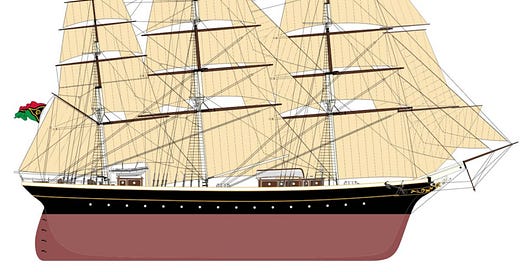

The article looks at the EcoClipper 500, currently being developed in the Netherlands by a founder of Dutch Far Transport, Jorne Langelaan, and based on a design of a 19th century sailing ship.

The EcoClipper 500. Image: EcoClipper

The rationale for adapting an old design is that at least it is proven, but there are quite a lot of issues as a result. Low Tech Magazine always goes into a decent amount of technical detail.

One of the reasons that it’s decided to look at the ship is because the design company has undertaken a lifecycle analysis, which may be the first for a sailing ship. It takes 1,200 tonnes of carbon to build the ship (most of the carbon is in steel), which means that if it has a lifetime of 50 years the carbon cost per kilometre-tonne of cargo is around 2 grammes, which is a fifth of a typical container ship. You could reduce this by using wood instead of steel, but there are far more shipyards who can work in steel than wood.

For a passenger, the carbon impact is around 10 grammes per kilometre, compared to 100 grammes per passenger-kilometre for a plane passenger.

The design doesn’t have a diesel engine so does rely on wind power. There’s a biodigester on board, which converts waste into gas for cooking purposes, and a pellet stove will generate heat. But it also needs some power, part of which can be generated by solar panels, part of which comes from two hydrogenerators attached to the hull. These work a lot better at higher speeds.

According to her hull speed, the EcoClipper500 will be able to sail a little over 16 knots at absolute top speed – this is double the minimum speed required to generate enough power. Achieving this speed will be rare, because it needs calm seas and strong winds from the right direction. Nevertheless, in good wind conditions, the ship easily sails fast enough to produce all electricity for use on board...

But if the wind dies down, the ship still needs power, so also has energy storage on board. And it turns out that people can get through quite a lot of electricity:

For example, if 60 people on board the ship would take a daily hot shower – which requires on average 2.1 kilowatt-hours of energy and 76.5 litres of water on land – total electricity use per day would be 126 kWh, more than double the energy the ship produces at a speed of 7.5 knots.

The EcoClipper can carry only 500 tonnes, compared to 50,000 tonnes for a container ship, and needs a crew of 12 to do it (a container ship crew is typically 20-25 people). So if this were to be a universal solution to maritime transport, we’d need millions of them.

The amount of cargo that was traded across the oceans in 2019 equals the freight capacity of 22.4 million EcoClippers. Assuming the EcoClipper500 can make 2-3 trips per year, we would need to build and operate at least 7.5 million ships, with a total crew of at least 90 million people. Those ships could only take 0.5 billion passengers (12 passengers and 8 trainees per ship), so we would need millions of ships and crew members more to replace international air traffic.

Even on this design, the ships could scale; the EcoClipper is some way short of the largest sailing ships ever built, and Jorne Langelaan is already imagining the 3,000 tonne version of the EcoClipper.

There are other wind-powered designs in development. As I understand it, all have higher carbon costs than the EcoClipper., but lower carbon costs that the typical container ship.

The Windships Association is promoting a a range of designs that enable ocean-going ships to deploy wind. It’s growing quickly, according to an article in The Engineer last year:

The association has grown from 12 to just over 100 members and partners since 2014: a clear reflection, says Allwright, of the growing seriousness with which wind propulsion is being treated. “We don’t see how we can make the speed and depth of the change without wind propulsion taking a significant load,” he told The Engineer.

One design effectively adds some wind turbines to the deck of the ship (I simplify). Others use large sails deployed to the side of the ship, managed remotely.

Some of these designs can be retrofitted, which is important given the life of most ocean going vessels. But reading the article, you also get the strong sense that we are in the early stages of an emerging technology, and that it will take a while for one of these technological models to assert itself as the dominant solution, and therefore build scale and credibility, and bring costs down.

Chris Craddock, at Lloyds Register, is quoted in The Engineer article:

“Wind technologies are generally acknowledged as a credible energy saving technology that could be applied to merchant shipping and reduce carbon emissions for certain ship types and sailing routes... However, since wind technologies are generally at a low level of technology readiness, there is a cautious interest by most of the market, with some of the larger charterers directly investing in technology development programs and pilot projects. As more technology demonstration pilot projects are successfully completed raising confidence in the technology... payback periods will drop.”

#2: What psilocybin does, at least to mice

The more we discover about psilocybin, the more reasons there seem to be to be optimistic about its possible effects. Psilocybin is the active ingredient in magic mushrooms, and there have already been some studies that suggest that it helps people dealing with depression.

But generally, we don’t know much about why.

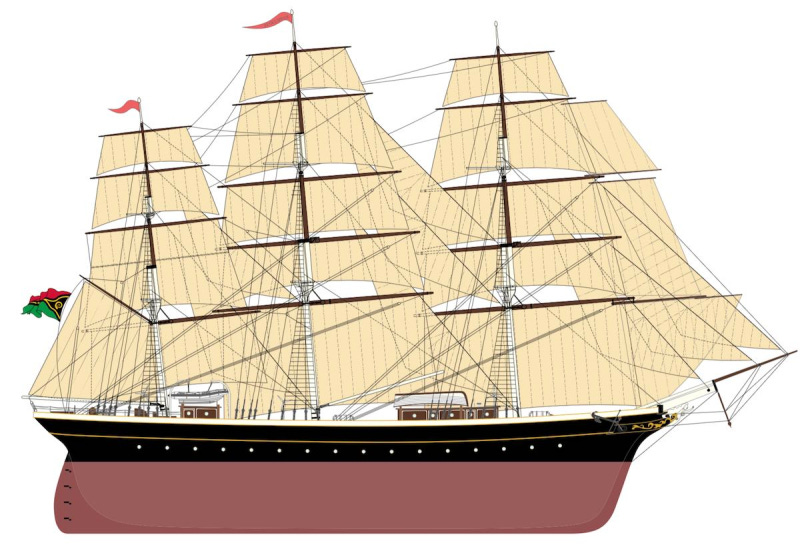

Image: Drug Science

Now some researchers at Yale have found that—in experiments involving mice—psilocybin increases the number of connections in neural networks in the frontal cortex, an area of the brain that is important for mood and cognition.

Obviously there are limitations to the study, and the researchers were quick to point them out:

“One caveat is obviously that this study is done in mice. Ideally, we would like to know what happens in humans, but that is not possible because of the kind of optical imaging that we did, which is very detailed and allows us to see individual sites of neuronal connections, but is also invasive and not suitable for humans,” Kwan explained.

“We know that the brain has many cell types. Here we study one type called the pyramidal neurons. For future studies, we have some ongoing projects to look at other cell types to see if they are also affected by psilocybin.”

j2t#142

If you are enjoying Just Two Things, please do send it on to a friend or colleague.