31st May 2023. Dams | Policy

Taking the dams down. // Why policy that everyone agrees on doesn’t happen.

Welcome to Just Two Things, which I try to publish three days a week. Some links may also appear on my blog from time to time. Links to the main articles are in cross-heads as well as the story. A reminder that if you don’t see Just Two Things in your inbox, it might have been routed to your spam filter. Comments are open.

1: Taking the dams down

Gregor MacDonald’s Gregor Letter looked at the trend in the United States to dismantle dams that have been built to generate hydropower. The newsletter is subscription-only, but I’m going to include a couple of extracts here. The reason that this is happening now is largely economic, but one of the drivers is a change in public values about the importance of local ecologies. The role of the Native American peoples in campaigning for these seems signifcant as well.

(The Boyle Dam on the Klamath River. Photo by Bobjgalindo, via Wikipedia. CC BY-SA 4.0)

MacDonald focusses the largest dam removal project in the US, on the Klamath River, which runs along the Oregon-California border, where four dams are being removed between now and the end of 2024:

ownership of the dams was transferred in 2021 from PacificCorp (a subsidiary of Berkshire Hathaway) to a public non-profit, The Klamath River Renewal Corporation , which will now oversee deconstruction.

Before the dams were built, the Klamath was the third-largest salmon run in the US, and evidence from other dam removal projects suggests that the local river biosystem will come back to life quickly:

To put it simply, the economic gains which can be achieved by dam removal now exceed the costs associated with maintaining old dams, despite their power output. This equation will obviously not hold true for many hydropower installations, especially the younger and larger dams.

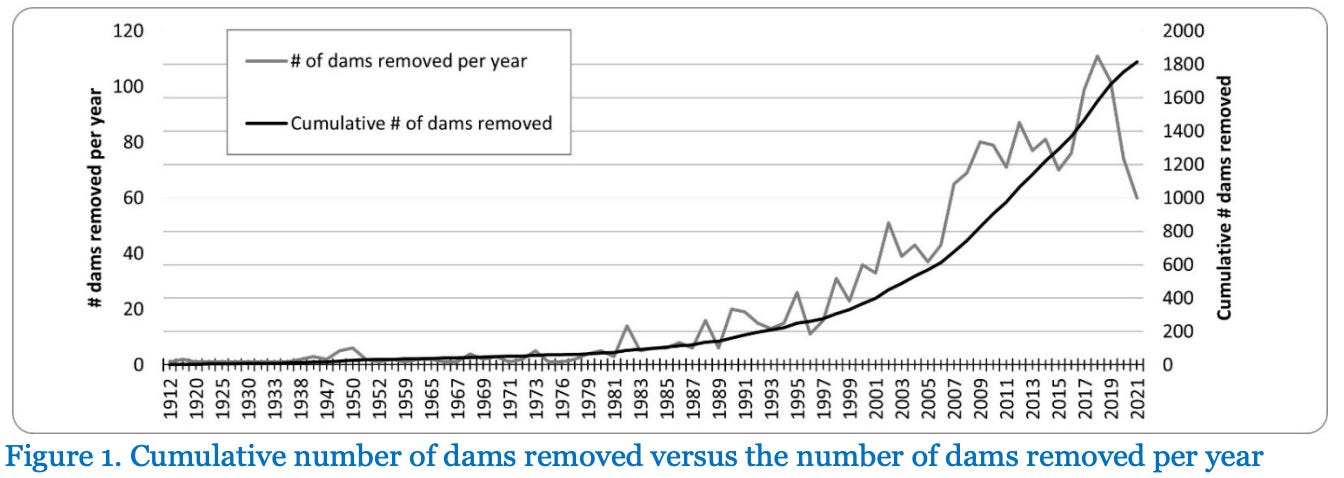

Dam removal has been speeding up over the past 30 years. This is tracked by American Rivers, which has a chart in its 2022 report ‘Free Rivers’:

(‘Free Rivers’: American Rivers, 2022)

MacDonald makes a parallel between the dismantling of old coal plants and old dams:

In the same way that much of the US coal fleet reached retirement age at the start of this century—which opened the way for natural gas and then wind and solar—the costs associated with keeping old dams running just aren’t worth it. If inefficient dams are kept running those costs are of course passed on to electricity rate-payers, as will some of the costs of closure.

The reason that PacificCorp was willing to pass the Klamath River dams over to a public non-profit organisation is that it monitors the costs and returns on its energy mix closely:

PacificCorp, like many other US utilities in recent years, has been undertaking a rapid transition from legacy generation to wind and solar. Indeed, PacificCorp has continually made public its analytical process, which employs Monte Carlo simulations to compare myriad generation mixes. And unsurprisingly, these old dams are just like the utility’s old coal assets: costing more money than they make.

MacDonald thinks that the plummeting price of renewables would make it unviable to build new hydropower in the US, and thinks they’d also be blocked by the public consultation processes involved.

He isn’t sure if this extends much beyond the US, but he does include data that suggests it is at least possible that globally we may have reached peak hydropower.

(Data: BP; chart: The Gregor Letter)

California and also Brazil for example both suffered steep hydro generation losses the past few years due to drought. Indeed, offshore wind is probably cheaper to build now than a new mega-dam; and given wind supply in the ocean, even offshore wind is likely cheaper than trying to build new hydropower. This may also be true for a country like China, which also may have already seen the peak in mega-dam building.

(2006 Klamath Dams protest. Photo: Patrick McCully via Wikipedia, CC BY 2.0)

There’s a local element to the Klamath River story as well. As I was doing a trivial amount of research, I discovered that there has been a 20-year campaign to get the river undammed, led by native American peoples, working with fishermen and activists. But the campaign goes back much further: the Yurok have been trying to regain their fishing rights to the river since the 1930s, in the face of adverse legal judgments and repression from police. Sometimes you need to take a long view on the future.

#2. Why policy that everyone agrees on doesn’t happen

At the Comment is Freed newsletter, Sam Freedman raises an genuinely interesting question: why does policy that everyone agrees is a good thing not get enacted? He explores this with a worked example about investing in preventative health.

Sam shares the responsibility for writing Comment is Freed with his father, Lawrence, the strategy guy. His own background is in and around Whitehall. Some of their posts sit behind a paywall, but not this one, I’m pleased to say.

So let’s just do the set-up to the argument. The initial point is that there aren’t that many good policy ideas around, and that “new ideas are extremely rare”. Of course, that means that you can drift into a cynical assessment of ideas when you hear them for the fifth or sixth time. So:

When I’m talking to a young think-tanker or political aide, whose enthusiam is not yet dimmed, I try not to dismiss ideas that have been doing the rounds for a while, but ask a different question: “given you’re not the first person to think of this why hasn’t it happened before?” Just because something hasn’t worked, or has been blocked, in the past, it doesn’t mean it can’t work now. But it is important to understand the history and explain why it can be different this time.

The origin of the post came from his reading a review for the British government of the British health system by the former Labour minister Patricia Hewitt. She argues that more money should be spent on preventative health, reducing the risks of illness in the first place. And of course, she’s not the first person to make this point. As Freedman says:

As far as I’m aware absolutely no one disagrees with this. Some dispute the idea that it will save much money, as healthier people live longer and ultimately may require more healthcare over their lives, but no one disagrees with the basic principle that it’s better to prevent illness than manage its consequences.

This includes the present government, so there’s no party political disagreement here. The report was welcomed by the present British Chancellor of the Exchequer (finance minister), Jeremy Hunt, who used to be the Health Secretary.

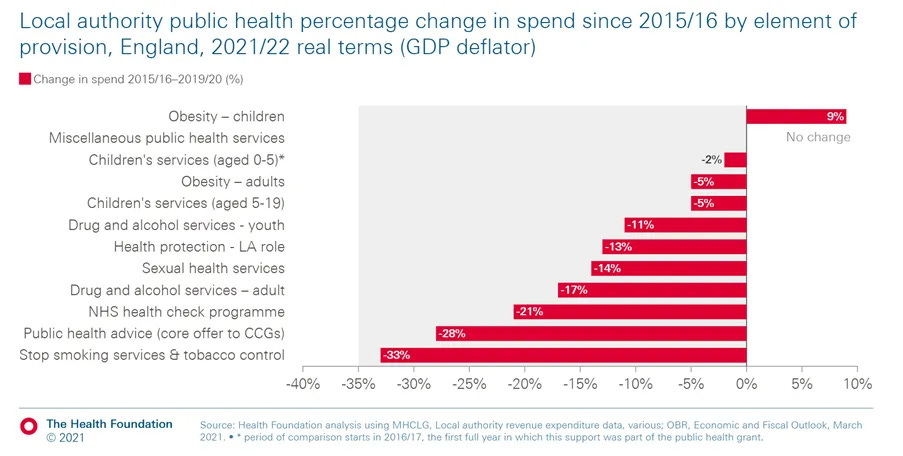

But as it turns out, the public health grant to local authorities, which is the main mechanism by which the British government promotes preventative health measures, has fallen by a quarter over the last six years. Here’s a chart that breaks that out a bit.

(Source: The Health Foundation via Comment Is Freed)

Apparently Hewitt explicitly raises the question of “why it will be different this time” in the report. Freedman finds her arguments on this “unconvincing”. So why do policy measures that everyone agrees on not get turned into policy?

In my experience there are three core categories of barrier that prevent the obvious ideas happening: spending rules; misdiagnosis; and fear of the electorate.

Freedman devotes a section of his post to each of these three (he acknowledges he may have missed reasons as well). I’m going to look at each of these briefly in turn.

Spending rules

He thinks that this is the reason why preventative health doesn’t get funded properly: the British government processes for allocating funding are notoriously unstrategic. This part of the explanation is quite technical, though other administrations have similar versions of this failure.

The Treasury’s objective in a spending review is to hit a target number that is driven by an arbitrary fiscal rule. To do this they have to overcome various obstacles including promises to protect highly politically sensitive budgets like hospitals and schools.

So elements of spending get moved to “unprotected” areas—like local government, as in this case—and can then be hacked away. Freedman notes that something similar happened to post-16 year old education (which, again, everyone agrees is a good thing) but was moved outside of the schools budget.

If the government’s entire strategic approach is being driven by a rigid spending limit then it will inevitably push money towards short-term priorities. Rehabilitation will get less focus than prisons which will get less focus than policing. Net zero will remain a long-term goal with limited upfront investment.

Of course, there’s a couple of things missing from this story. The first is a government that was happy to cut public spending, for ideological reasons, even while it was clear that this was undermining the public fabric of the country. The second is more structural—that the whole discourse about government budget-setting is about the “big beasts” in the Cabinet jousting with each other and the Treasury, as stags in the autumn, to protect their departmental budgets at the expense of their colleagues. (The type of people who are successful in politics are often not that collaborative by nature). Their headline departmental figure, which is in the news today and tomorrow and next week, is more important to them than the consequences, which happen later. Often years later.

(Rutting stags, Richmond Park. Photo, Peter Trimming, Geograph.org.uk, CC BY-SA 2.0)

Misdiagnosis

This category is of things that seem sensible but are misunderstood. Freedman uses the example of vocational training, which ought to be more highly valued than it is. Britain, like other countries, has gaps in employment categories that require vocational skills.

But, he suggests, the reason that vocational training is under-valued is that all the signals from the labour market value work that requires a degree. (Germany, which is usually cited as a country that has cracked this, actually has similar problems.) Is there a way from governments to create “esteem” around vocational or technical qualifications? Well, since Victoria’s consort, Prince Albert, was worrying about the same issue in the mid-19th century, maybe not.

Fear of the electorate

This includes a set of policies that no-one is willing to defend but has at least as many winners as losers, so no-one is willing to advocate. It’s better not to poke a stick into a hole in the ground when you know there are hornets inside. He gives the example of Britain’s council tax system, which is supposed to be linked to house values, but hasn’t been re-banded since it was introduced 32 years ago (as a fix for the UK ‘poll tax’, one of the great British policy fiascos):

I’ve never seen any politician try to defend the status quo. On the rare occasion they’re asked about it they’ll mumble something about it being complex and how it needs careful consideration or some such. Depending on how it was done it could raise some much needed money.

---

One of the ways of dealing with the lack of strategy in policy-making is to have policies that are jointly owned by different departments, so that individual departments don’t dump their problems onto others. (Health and social care is one example of this; drugs policy, which involves health and crime, is another.) The Scottish Government has tried this approach, with shared Departmental targets. It’s hard to find accounts of how it has worked. The Welsh government has tried to address this integration issue at the point of delivery, with its Public Service Boards.

But I think that there’s another issue here, at least in the preventative health example, that Freedman overlooks. This is the relative power of the institutions and professions who are involved. Health trusts are large, locally influential organisations, and the doctors who work in them tend to be higher status than their colleagues outside of them. This reinforces the medical model of health.

And, in general, people who work in preventative health tend to be lower status and often working in the community. Even if they are attached to the health trusts, they are often marginalised. Actor analysis matters. Freedman, though, is right to conclude:

(I)deas are overrated in policy. The real skill is figuring out how to make the ideas we already have happen... It sounds less exciting than coming up with a big new idea, but it’s a lot more useful.

j2t#461

If you are enjoying Just Two Things, please do send it on to a friend or colleague.