31 May 2022. Cities | Writing

Sacred civics and seventh generation cities. // The four stages of writing.

Welcome to Just Two Things, which I try to publish daily, five days a week. Some links may also appear on my blog from time to time. Links to the main articles are in cross-heads as well as the story. Recent editions are archived and searchable on Wordpress. And a reminder that if you don’t see Just Two Things in your inbox, it might have been routed to your spam filter.

1: Sacred civics and seventh generation cities

I spent some of my weekend reading the first chapter of Sacred Civics, a new book about ‘building seven generation cities’. The phrasing of the sub-title might be a bit awry—most cities have been around for a lot more than seven generations—but the intention is to think about how cities might be different if they adhered to the “seventh generation principle”.

This is from indigenous “philosophy. Ceremony and natural law”, and is defined in the preface, from the Gayanashagowa, as

In our every deliberation, we must consider the impact of our decisions on the next seven generations.

In the introduction, written by the book’s editors, Jayne Engle, Julian Agyeman, and Tanya Chiang-Tiam-Fook, they explore some of the principles and questions this involves, and propose a model to help to think about it.

First, perhaps, a definition of ‘sacred civics’. ‘Sacred’, or ‘spiritual’, as in “a divine or mystical force within all living beings,” relating to

a sense of connection between people and with nature, a shared sense of purpose and meaning that flows from that, and which translates to a shared sense of how to co-exist.

“Civics”: ‘of the city’.

There are a few things that follow from this. Sacred cities, they say, invite us to deconstruct why cities exist and how we build them, and why. They ground us in “a sense of purpose greater than ourselves.” And they are transcendent, meaning that they fight the “technocratic tendency to reduce cities to categorisation by issue, sector, discipline, or component parts."

So the sacred cities argument has a set of core arguments (yes, this has a slightly academic tone):

Cities are critical sites of societal transformation and civilisational change.

Briefly, cities are the largest sets of systems shaped by humans. The majority of people on the planet live in them – and so there is a pressing need to reconsider how we build them. " They quote Geoffrey West’s book Scale, in which he says "the future of humanity and the long-term sustainability of the planet are inextricably linked to the fate of our cities."

Holism is foundational to evolving social constructions and upending assumptions that currently shape most city building.

Seeing holistically can unlock a different set of ways to build cities. This includes intellectual, physical, emotional, and spiritual dimensions of people. Adding a spiritual dimension represents, they say, the potential of the people, cities and societies capabilities to transform – and transcend – environments.

Enacting a sacred civics invites an ennobling of the city builders and peacekeepers to honour higher order responsibilities.

The ethos of a sacred civics ennobles people "to honour sacred responsibilities of care for another and all life.” In turn, this involves new sets of accountabilities for governments, institutions, and systems. These accountabilities include accountabilities to all peoples, to future generations, and to the Earth.

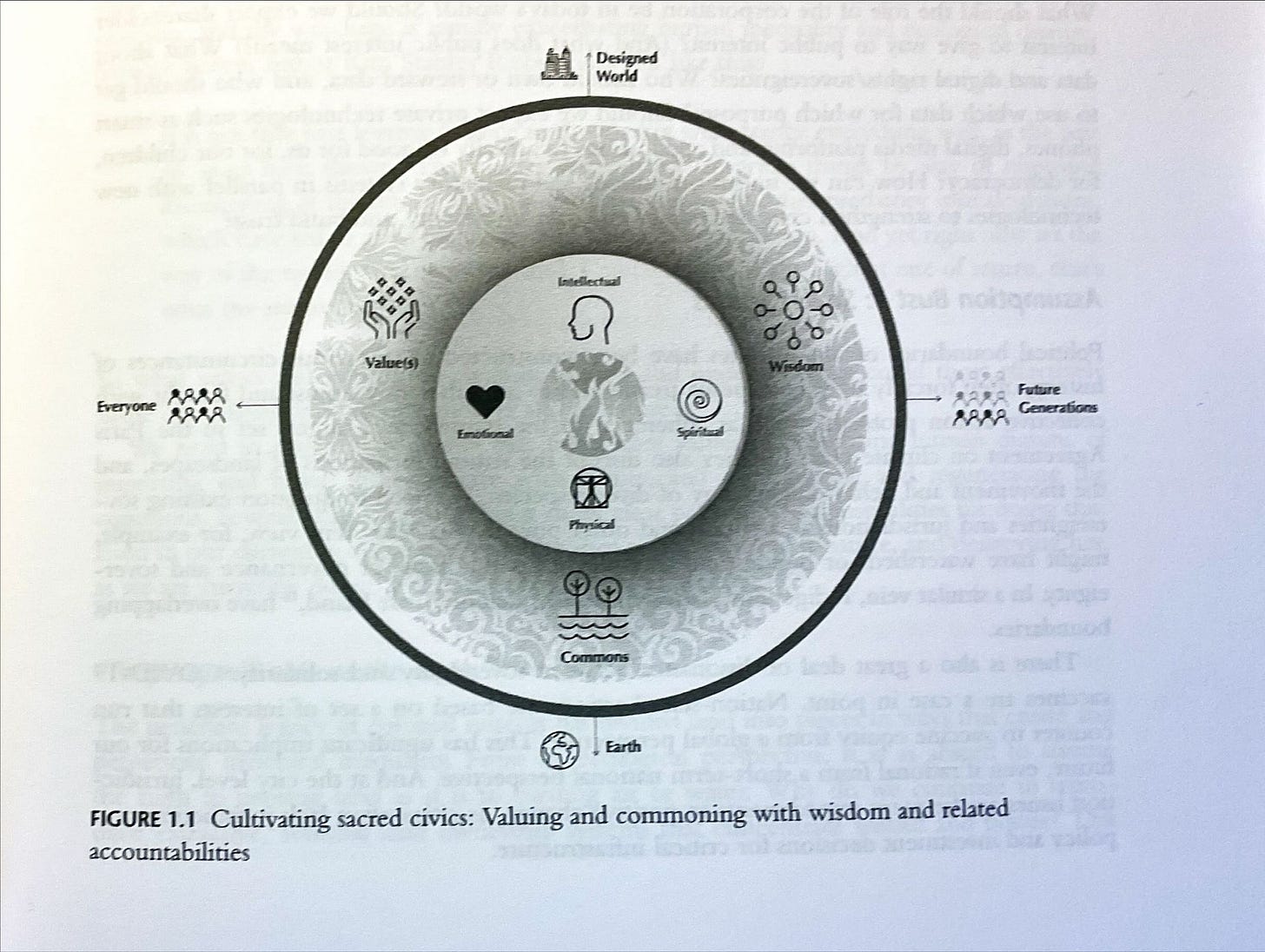

This all comes with a natty diagram that connects these different things together, which reminded me a little of some of the questions that the Doughnut Economics Action Lab uses in its work with places, although those are influenced more by geography and economics.

At some point I can see that I’m going to have to recreate it, but for the moment, I’ve just photographed the diagram in the book.

(Source: Jayne Engle, Julian Agyeman, and Tanya Chiang-Tiam-Fook, Sacred Civics.)

On the outside of the circle, then, there is at the top the designed world, and at the bottom, the Earth. To the left, everyone – everyone now – and to the right future generations. In the middle, these correspond to, respectively, the intellectual and physical, and the emotional and the spiritual. And connecting these, there is a layer which includes values, wisdom, and the commons.

Moving towards this model, and this type of participation, involves changing some of the current assumptions that govern our cities. They list the three big ones:

Ownership/property. In our current cities, the right to private ownership, particularly of land, is elevated. But perhaps land should be self-sovereign. Or at the very least, it needs different models of stewardship and guardianship.

Role of corporations: Again, although shareholder interest is giving way to ‘stakeholder interest’, as far as corporations are concerned, this probably doesn’t go far enough. What do public interest corporations look like? (They also mention, later, the ownership of urban data, successfully reclaimed for the city by Barcelona.)

Sovereignties: Political boundaries are often an accident of history, or of war. They don’t fit well onto ecosystems. We might need jurisdictions that are more respectful of ecological systems like watersheds or biomes. And we might want new jurisdictions that overlap, or which operate in different ways for different type of systems.

Well, more on this as I get further into the book. But there’s clearly a critical set of questions about both governance and ownership. They quote Foster and Iaione on the kinds of institutions that govern commons:

commons based institutions are characterised bye move away from a vertically (top down) oriented world to a horizontally organised one in which the state, citizens, and a variety of other actors Caleborate and take responsibility for common resources.

This reminded me of one Elinor Ostrom’s findings about the way that commons are governed, which is also mentioned in the chapter. Or, to put it another way, as the authors write, "our largest institutions and governments are not built for the age of long emergencies we now inhabit.”

2: The four stages of writing

Betty Sue Flowers is well-known writer and editor, who’s engaged with futures and systems thinking down the years, both as a writer of a couple of sets of Shell’s scenarios and the co-author of Presence.

But she’s here today as the writer of a short post about writing that I was pointed to by my colleague Cat Tully, who had talked to Betty Sue Flowers recently about being stuck getting started on a book.

She says that there are four roles when writing: madman, architect, carpenter and judge.

(Henriette Browne, ‘Girl Writing’, c. 1870. V&A Museum. Image: Gandalf’s Gallery/flickr, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

The madman and the judge are at opposite ends of the spectrum; they tend to get locked together in a way that locks up the writing process:

(Y)our 'madman'... is full of ideas, writes crazily and perhaps rather sloppily, gets carried away by enthusiasm or anger, and if really let loose, could turn out ten pages an hour.

"(T)he 'judge'... (has) been educated and knows a sentence fragment when he sees one. He peers over your shoulder and says, 'That's trash!' with such authority that the madman loses his crazy confidence and shrivels up.

But the judge can’t create anything. So if you’re not going to get stuck, you need to separate out these energies.

"So start by promising your judge that you'll get around to asking his opinion, but not now. And then let the madman energy flow. Find what interests you in the topic, the question or emotion that it raises in you, and respond as you might to a friend—or an enemy. Talk on paper, page after page, and don't stop to judge or correct sentences. Then, after a set amount of time, perhaps, stop and gather the paper up and wait a day.

But it’s still not time to let the judge back in again. First, you need the architect.

She will read the wild scribblings saved from the night before and pick out maybe a tenth of the jottings as relevant or interesting. (You can see immediately that the architect is not sentimental about what the madman wrote...). Her job is simply to select large chunks of material and to arrange them in a pattern that might form an argument. The thinking here is large, organizational, paragraph level thinking-the architect doesn't worry about sentence structure.

The person who worries about sentence structure is the carpenter, who

enters after the essay has been hewn into large chunks of related ideas. The carpenter nails these ideas together in a logical sequence, making sure each sentence is clearly written, contributes to the argument of the paragraph, and leads logically and gracefully to the next sentence.

And only after that does the judge get their turn.

Punctuation, spelling, grammar, tone-all the details which result in a polished essay become important only in this last stage... Save details for the judge."

j2t#322

If you are enjoying Just Two Things, please do send it on to a friend or colleague.