30 March 2022. Music | Robots

The male world of the classical concert programme. Investigating robot accidents

Welcome to Just Two Things, which I try to publish daily, five days a week. Some links may also appear on my blog from time to time. Links to the main articles are in cross-heads as well as the story. Recent editions are archived and searchable on Wordpress.

1: The male world of the classical concert programme

I ended up talking to the singer Gabriella di Laccio at a party last week, who’s also been the driving force behind a charity, Donne, and a website that looks to create greater awareness of women classical composers.

One of the features of the site is ‘The Big List’—which features several thousand women composers, almost all of them neglected by classical orchestras, going back to early music.

Another is research—now in its third year—into the number of concerts by classical orchestras that include pieces by women composers, and the proportion of pieces by women.

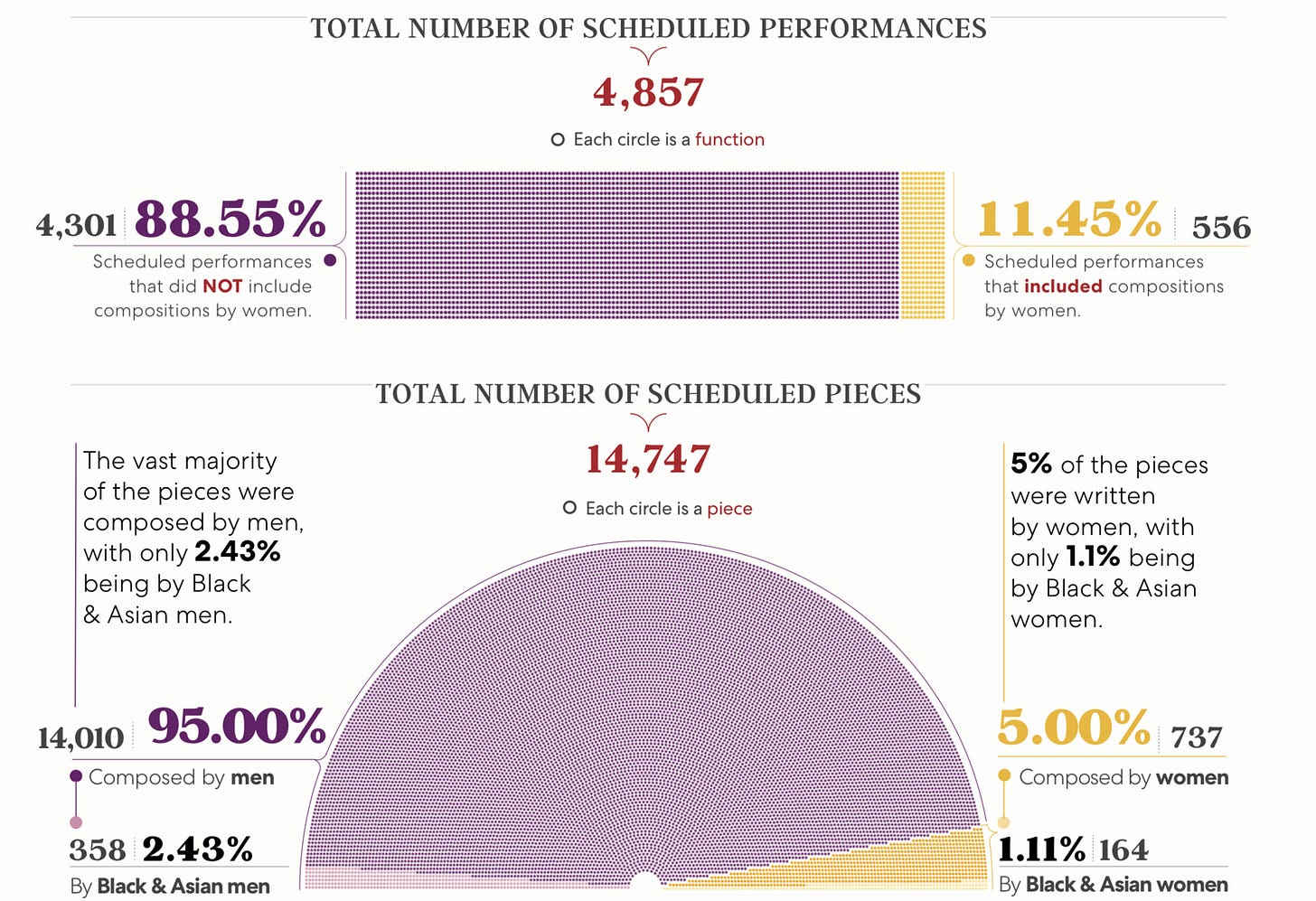

The research tracks performance by 100 orchestras from 27 countries, which is now collected in a chunky spreadsheet. Here’s the headline 2020-21 data on that:

(Source: Donne)

So: 88% of concerts featured only pieces written by men (or nothing in the programme by a woman composer), and of the total number of pieces played, only 5% of them were by women.

There are some orchestras that managed to go through the whole year without playing a single composition by a woman composer, notably the Vienna Symphony Orchestra, over the course of 100 performances, and the Sydney Symphony Orchestra, over 103. On its website, the Sydney Orchestra projects a good story about inclusiveness—it’s just a shame about the repertoire.

The report has a number of responses to the question, ‘Why is it important for the music industry to have equality and diversity as a goal?’.

Picking out a couple of the replies, the composer Anna Appleby says:

They said that their music was universal, but the music they played was only from one tiny corner of the universe. They said our music was too political, but we didn’t look at all like their politicians. So if we are too political for the concert hall and too artistic for the debating chamber, where in the universe do we sit? If we continue to programme the same pieces for the rest of eternity, we are consigning the concert hall to be a museum, but even museums reckon with their past through the eyes of the present, and reframe the biases which have bought their exhibits.

James Murphy, of the Royal Philharmonia, pointed to the relationship between performance and its audiences:

Music can enliven and empower us all. But people are less inclined to engage with it if they don’t see themselves in it. That risks marginalising and diminishing something that ought to be universally cherished. History’s done a brilliant job of making us think classical music is white and male. It’s not.

Of course, classical music is intensely conservative—and dominated by the ‘canon’, almost all of which is work by dead white men. Some pieces by women composers are now creeping into the edges of the canon—the black American composer Florence Price, performed at the Proms last year, seems to be getting there.

And obviously the cost of doing new classical pieces is higher—you need an orchestra, the orchestra needs scores, rehearsal time, and so on. This may be a reason why when orchestras do play pieces by women, thee same pieces tend to pop up in different places.

But I think this may start to change, and perhaps quite quickly. I’m not holding my breath for #TimesupForClassicalMusic, and I suspect that it may take some time for audiences to notice—they tend to be older rather than younger, and more conservative about concert programming.

But younger players will start to lobby for a more representative mix in concerts, and I suspect that some critics may start to call out all-male programmes. And I’m confident that orchestra sponsors will also start to notice. It can’t be good for Rolex, which sponsors the Vienna Symphony Orchestra, to be associated with a cultural product that is tone-deaf to gender.

Some of the ‘how’ of change was captured for me by the composer Ella Jarman-Pinto decided to reframe the question that was asked about why this was important:

I could think of a thousand reasons - but first, let’s turn the question on its head: Why does the music industry work to to actively exclude people? Because it’s easier? Because we’re afraid? Because we’re lazy?... So what does it say about us?

Much of Gabriela’s work on the project—she started in 2015–has been unpaid, while she’s also been juggling her singing career, and she acknowledged that this was exhausting. She clearly needs to be able to hand Donne on to an executive director to take it forward. So if there’s a foundation out there that funds gender issues in the performing arts, you should get in touch with her.

In the meantime, if you want to hear more music by women composers, the Donne report comes with a link to a YouTube playlist.

And here’s a starter, from the mid-20th century Welsh composer Grace Williams:

2: Investigating robot accidents

Robots make mistakes. And they will make more of them, as they become more common, and are developed to do more complex tasks, which will involve more complex algorithms that are less well understood.

By mistakes, we might mean a bionic arm that misinterprets its owner’s intention and causes a vehicle to crash. Or a care robot that misses the distress call of an elderly person who has fallen. Or a service robot that tips a drink down someone’s front. (One can think of more serious mistakes as well, in logistics warehouses that involve a complex interaction between robot shifters and human pickers).

(Bionic handshake. Photo by Starwarsrey, via Wikimedia. CC BY-SA 4.0)

This is the subject of a short piece in The Conversation by Keri Grieman of Oxford University:

The more complex things a robot is capable of, the more types of information it has to interpret. It also may be assessing multiple sources of one type of data, such as, in the case of aural data, a live voice, a radio, and the wind.

As robots become more complex and are able to act on a variety of information, it becomes even more important to determine which information the robot acted on, particularly when harm is caused.

Of course, robots aren’t malicious, at least, not yet. We’re still dealing with hardware and software failures here. So we need to be able to work out why the robot did what it did, based on the inputs it had, and the way it processed these inputs.

In the example of the bionic arm, was it a miscommunication between the user and the hand? Did the robot confuse multiple signals? Lock unexpectedly? In the example of the person falling over, could the robot not “hear” the call for help over a loud fan? Or did it have trouble interpreting the user’s speech?

Grieman is part of the RoboTips project, subtitled ‘Responsible robots for the digital economy”. Researchers there are developing an ‘ethical black box’ for the robot—based on the idea of the aviation black box, or flight recorder—which will keep a full record of what the robot did, and so will enable researchers to work out what happens when something goes wrong. The ethical black box is

an internal record of the robot’s inputs and corresponding actions. The ethical black box is designed for each type of robot it inhabits and is built to record all information that the robot acts on. This can be voice, visual, or even brainwave activity.

It’s currently being tested in the laboratory. The intention is that these will be fitted as standard in all robots to allow us to work out what has happened when things go wrong. This is a good idea, and I’m glad that the RoboTips researchers are working on it.

Some thoughts from me on this: flight recorders work because planes are complicated and not complex (and also because plane crashes happen in an industry that probably has the most developed safety culture in the world). As algorithms become more opaque, and potentially layered on other algorithms, it’s possible that even having access to the record of the incident in a recorder won’t tell us what went wrong with a robot.

It’s also not clear that the owners of systems will necessarily want to stamp out mistakes when it is easier to blame users (as the British Post Office did, now scandalously, over the faults in its Fujitsu-supplied Horizon accounting software).

And the history of the flight recorder is relevant here. It was introduced, certainly in the US, by the American aviation regulator, to improve flight safety. At the moment, robotics is a governance nightmare, with different industries covered by different agencies, certainly in the EU and the US.

A recent article in Mobile magazine argues that we need better robotics regulation. It wonders if the insurance industry might be the mechanism that drives this, by requiring businesses that need insurance for their robots to sign up to a set of safety and investigation protocols.

j2t#290

If you are enjoying Just Two Things, please do send it on to a friend or colleague.