31 January 2022. Money | Past

Anti money laundering processes are an expensive failure. The past is another country.

Welcome to Just Two Things, which I try to publish daily, five days a week. Some links may also appear on my blog from time to time. Links to the main articles are in cross-heads as well as the story. Recent editions are archived and searchable on Wordpress.

1: Anti-money laundering processes are an expensive failure

I had to engage a lawyer recently, so went through the usual cumbersome ‘Know Your Customer’ (KYC)/ Customer Due Diligence (CDD) process—sharing my passport to prove I was who I said I was and a recent hard copy utility bill (and who really has these anymore?) to prove that I lived where I said I lived. This is all to ensure that I wasn’t really a money launderer rather than a citizen trying to fulfil some legal obligations.

So I was interested to read a post by the digital identity expert David Birch which says that this whole paraphernalia of performative anti-money laundering (AML) is one of the least successful pieces of public policy ever introduced. (Thanks to John Naughton for the link).

Birch points to quite a lot of evidence for this. The first is that the ratio between compliance costs for banks and so on to actual criminal loot seized is massive: of the order of a hundred to one:

study published last year by financial-crime expert Ronald Pol concluded that the global AML system could be "the world's least effective policy experiment " and that compliance costs for banks and other businesses could be more than 100 times higher than the amount of laundered loot seized. (That may seem astounding, but it is correct. The UN estimates for the seizure of criminal assets globally are in the region of $1.5 billon while the Lexis-Nexis estimate for the global costs of AML compliance are in the region of $180 billion.)

Second, this isn’t just unsustainable for cost reasons. It’s true that the current rules neither prevent or capture crime. One recent estimate says that 99% of dirty money washes through the financial system unnoticed. Another paper calls the whole global anti money laundering/terrorist finance regime “almost completely ineffective”. Entertainingly this paper is called, “Uncomfortable truths? ML=BS and AML= BS squared”.

But all of this also has a bad effect on institutional cultures:

Instead, says (Lisa Moyle), they risk making financial institutions so overly cautious that they only serve to exacerbate the problems of the marginalised and excluded as well as creating barriers for honest customers.

The effects might be worse than this. These ineffective Customer Due Diligence processes impose a bureaucratic cost that larger organisations can sustain more easily than smaller ones.

And the whole regime requires us constantly to hand over valuable personal data to the financial system, which sooner or later, someone is going to steal.

Summing up the story so far, Birch says:

Not only does the regime we have now do little to hamper terrorists, money launderers, drug dealers, corrupt politicians or mafia treasurers, it does massively inconvenience law-abiding citizens going about their daily business. According to an interesting paper in the Journal of Money Laundering Control 17(3), the Financial Action Task Force (FATF) identification principles, guidance and practices have resulted in "largely bureaucratic" processes that do not ensure that identity fraud is effectively prevented.

David Birch is a world leader in digital identity, and he has a digital solution that might reduce the costs and the risks involved, which I might come back to another day. (Or you can read his longish post). This, he suggests, might improve the balance between costs and the maintenance of privacy.

My interest is at least as much about why we’ve ended up with this system, since—in policy terms at least—it seems to benefit the wrong people.

One of the rules in looking at systems is identifying what the system is doing, rather than what it says it is doing. In this case it only takes a short step to conclude that it’s in the interests of the global financial system to have criminal money washing around more or less unimpeded.

The MP David Davis alluded to this is a speed in Parliament recently, as Charles Arthur noted last week. I’m quoting from Hansard here:

One of those suing (Catherine) Belton (over her book ‘Putin’s People’)—the final one—was Roman Abramovich, the multi-billionaire owner of Chelsea football club. Abramovich claimed that Belton’s book alleged that he had a corrupt relationship with the Russian President and was making payments into Kremlin slush funds... We are speaking here of the man who manages President Putin’s private economic affairs, according to the Spanish national intelligence committee. This is a man who was refused a Swiss residency permit, due to suspected involvement in money laundering and contacts with criminal organisations.

There’s more in the speech, but it’s increasingly a commonplace that the City of London is the heart of the world’s money laundering flows, and that by and large the British state doesn’t care as long as British-based bankers and corporate layers collect their fees along the way. (If this seems contrary to the usual way of thinking about the City of London, or investment banks, or ‘magic circle’ law firms, it’s worth looking at the work of Nicholas Shaxson or Oliver Bullough.)

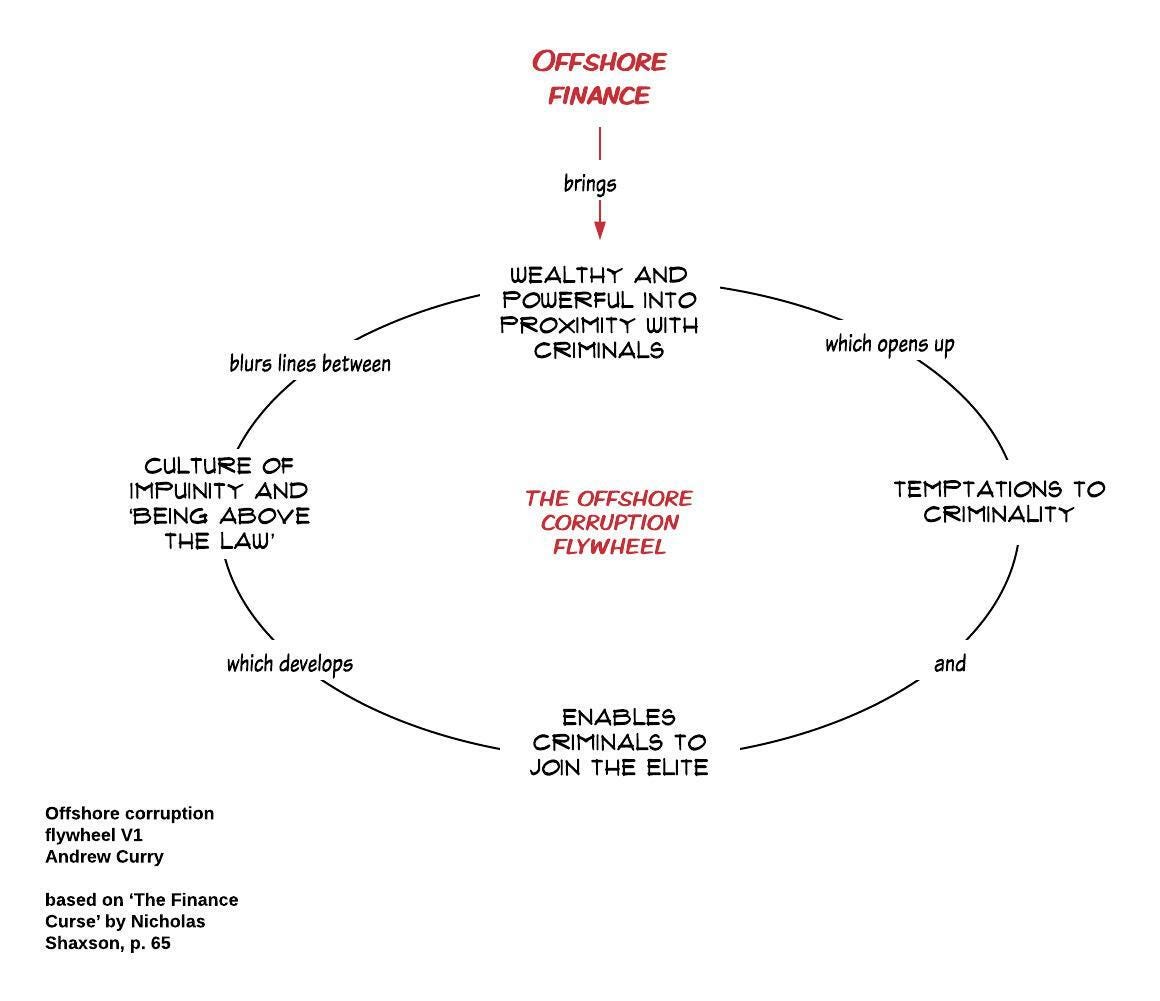

In The Finance Curse, Shaxson suggests that one problem with being a centre through which dirty money flows is that everybody in the financial and political elites gets touched by it. It also influences political decisions. I turned his explanation of this on p. 60 into a flywheel to make the process clearer.

Before you protest, some of these benefits may be indirect: funding, say, a political party, or a political campaign, or a thinktank, rather than individual lifestyles.

The conclusion seems to be that our money laundering arrangements are the way they are because those arrangements benefit the rich and powerful, and especially financial interests. In Moneyland Bullough quotes the economist and campaigner James Henry:

“We are up against one of society’s most well entrenched interest groups. After all, there’s no interest group more rich and powerful than the rich and powerful.”

2: The past is another country

Cambridge Imprint is an upmarket, online stationery business, and its occasional newsletters are always literate and interesting. (The author is unidentified, but the clues say it might be it may be Claerwen James, Clive James’ daughter, who is one of the partners).

Its most recent newsletter was a charming discussion of the way we see the past, inspired by a visit to their printers, in east London:

The Bethnal Green gasometers and the Regent's Canal which flows past them are particular landmarks we enjoy. Gasometers have been a structure of utter fascination to me since childhood. Once upon a time Cambridge had a whole crop of them down on the right bank of the river as it flows out of town. They are long gone, but it's always a pleasure to see one elsewhere... They are as majestic and baffling as the Himalayas.

(Photo: Cambridge Imprint).

We don’t really need gasometers these days, so the ones that are left are relics of a different energy infrastructure. The gasometer is by a canal—a relic of a different transport infrastructure—and building both would have caused disruption at the time, probably to poorer communities. And this leads to a riff on the difficulty of getting used to change. During the pandemic Cambridge Imprint had to move offices, and also discovered recently that the bank branch they had used over the last decade had abruptly been closed:

Hidden on Sidney Street was a tiny unmodernised branch of Barclays which the higher banking powers seemed to have overlooked: it still had the cashiers' desks with their glass screens and the sliding hatch in the counter through which you slipped your papers. Those of us (and we were legion) who preferred to talk to a human rather than interact with a machine continued thankfully to use it in preference to the huge shiny indifferent rather airport-like branch in the city centre. Suddenly last month it was gone as if it had never been - the windows painted over, the signage gone... To the young lady with the blond hair who was always so polite and helpful - we will miss you.

Well, maybe this is just so much nostalgia, but there’s something sitting behind it about the personal and physical qualities of exchange that sit behind many everyday transactions, or used to, and which are being eroded by our digital systems and digital infrastructure. We gain from change, but we also lose things. (And perhaps there’s a tiny anthropological case to made for Customer Due Disclosure, discussed above, as a modern ritual for meeting with professional advisers for the first time.)

The specific and granular qualities of everyday life are also landmarks for which one can feel intense nostalgia, and a desire to hold onto them even when their utility is gone. Perhaps when you no longer had to get an operator to manually connect you on the telephone that too seemed like an unseemly and inhuman loss of politeness, deliberation and courtesy. So many innovations, while immeasurably improving the swiftness and convenience of everyday tasks, remove the appreciation that we are all people, exchanging goods and services with one another for our mutual benefit.

j2t#253

If you are enjoying Just Two Things, please do send it on to a friend or colleague.