Welcome to Just Two Things, which I try to write daily, five days a week. Some links may also appear on my blog from time to time. Links to the main articles are in cross-heads as well as the story.

#1: Visions of a post-carbon future

The Museum of Carbon Ruins project, led I think by Lund University, is a couple of years old now, but my sometime colleague Paul Graham Raven has recently written a piece about it on the Transforming Society blog:

Is it an art intervention? An immersive research exhibit on decarbonisation? Climate change theatre? It’s all of these things, in a way—the common thread being the creation of a space of speculation about climate change.

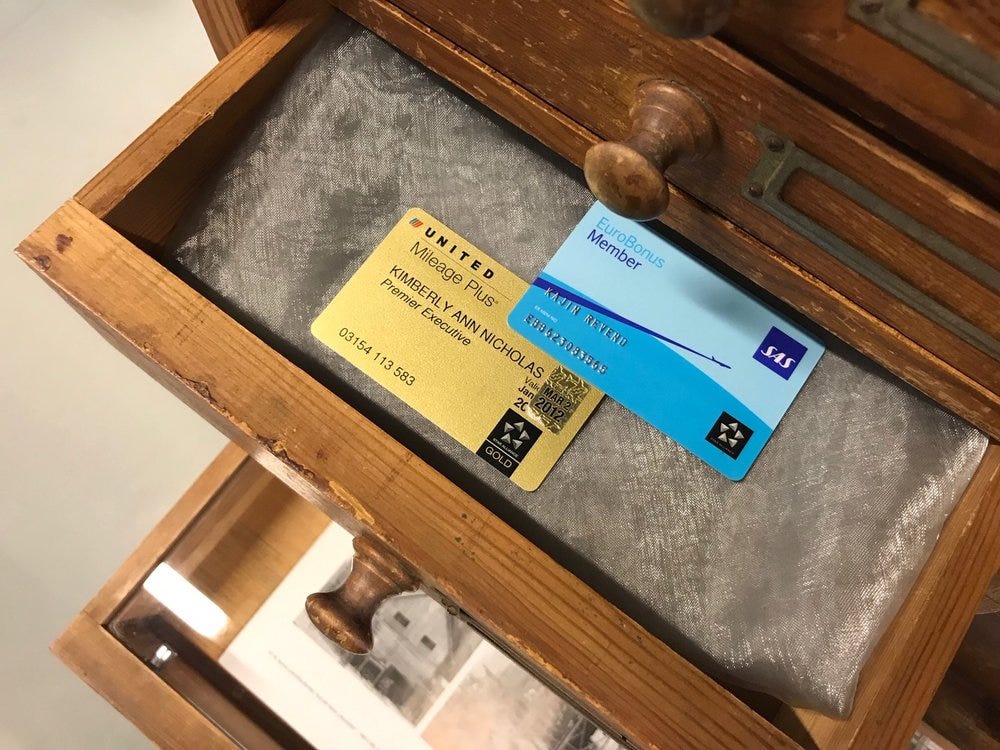

What it is, in practice, is a series of speculative designs from the year 2053, in a world in which we have managed a successful transition away from fossil fuel dependency. Exhibits record imagined things that helped make the transition possible—and more tellingly, actual artefacts from that fossil dependent past (i.e. our fossil dependent present) that are now found, well, in a museum. Like these airline loyalty cards, for example.

(Source: Museum of Carbon Ruins)

In his article, Paul opens up the question of why academics are messing around with design fictions at all. He offers three answers.

The first is about making the futures concrete. (As an aside: in the case of the Museum, there’s an exhibit of a concrete core drill that literally makes the past concrete.) What he means by this is a lot of the discussion about climate change is at the level of the abstract: IPCC reports, aspirations to get to a ‘net zero’ world. It is not material that is easy to engage with. By making the expressions of these issues physical, concrete, it brings questions about the carbon transition back into the material world.

The second, connecting principle, is to situate climate change, by making it local:

situating climate change means talking about possible futures in terms of the audience’s own surroundings. How warm might it be by mid-April in Malmö, Manchester or Mogadishu? What familiar crops and garden plants might no longer thrive, and what might they have been replaced with?

It’s about place, but it’s also about people. No speculative space can include everyone’s perspectives, but it can welcome diversity. And that, in turn is connected to the third principle: democratisation.

One of the better transitions in futures work over the past 20 years has been away from the expert-led and often technical constructions of possible futures that dominated the discourse in the 70s, 80s, and 90s, through the work of organisations such as Shell, RAND, and the Global Business Network. Democratisation is a valuable principle in its own right, but as Paul points out, it’s also more effective:

Showing people our concretised and situated projections of their future environment, and then asking them how they think they might want to live within that context, may end up producing answers that we experts would never have thought of. We’re sure to get some answers that make us uncomfortable, too – but that’s perhaps the best reason of all for doing it.

In the same vein, it’s also worth checking the Notterdam guide book which Paul Graham Raven edited—a tourist guide to a European coastal city which is a found object from the year 2045. Like the Museum of Carbon Ruins, it sets out to construct a speculative future that can be the start of conversations in the future.

#2: Talking to animals—and birds

Harpers has a piece in which Lauren Markham explores our ability to communicate with creatures, starting with a “crow whisperer” who helps a couple threatened by a hostile flock (or “murder”) of crows.

“What do you know about crows?” he posted on Facebook. “Namely, conflict resolution?” Friends and family members expressed concern and offered suggestions... A few neighbors chimed in with their own recommendation: he needed to talk to Yvette Buigues, the local crow whisperer. Adam wrote her a message, and she promised to come over right away.

The crows descended, cawing loudly, as soon as Buigues entered the backyard the next day. She began, she told me later, by offering soothing words, and sending the birds unspoken messages: that she came in peace, that she was there to help.

Of course, the year of lockdown has brought us into closer contact with the other creatures whose habitat we share. Sometimes this is because they have been bolder as we have been quieter, sometimes because they were in more distress. It might also be because, confined to smaller spaces, that we have noticed more.

These stories of animal invasion—even the more menacing ones—were a balm, a necessary distraction from the horrors of the news. And yet something more profound seemed to be at stake. What if dive-bombing crows were not just a reflection of the pandemic’s disruption but a glimpse of a world where the boundaries between humans and the rest of the animal kingdom had blurred? As I began to imagine a post-pandemic world—one with a more equitable education system, health care for all, accessible public spaces, a less exploitative economy—I wondered whether there was also an opportunity to rethink the relationship between humans and the natural environment.

Markham uses Yvette Buiges’ work—she doesn’t just do crows—as a way to understand more about the possibilities of human-animal communication. Buigues herself is a little sceptical of her skill: “I’m just an old punk rocker,” she says, “who happens to be able to communicate with animals.” Of course, she talks to scientists who are sceptical of whether it is possible to “talk” to animals or birds. The ethologist Frans de Waal tells her that animal communicators can be “classic grifters”, playing off the humans. Controlled experiments tend to fail to replicate outcomes. Nonetheless, he’s not completely sceptical:

Animals communicate in myriad verbal and nonverbal languages, de Waal emphasized, which humans are capable of learning to decipher. Likewise, animals pick up on human cues for their own protection, and out of something like love. “Animal intelligence is beautiful enough, amazing enough,” de Waal told me. “You don’t need to add fictional elements to it. It’s already by itself quite remarkable.”

It’s one of those long, well-researched, well-reported articles that American magazines do better than anyone else. Along the way, at least for me, it tested some ideas about how we know what we know. And reminded me—as Nora Bateson reminds us in her work on “warm data”—that sometimes interstitial behaviour, in the connections within systems, are hard to replicate through conventional science.

Updates: I took part in a panel a few weeks ago on post-pandemic transport. The moderator of that discussion, the indefatigable Glenn Lyons, has just published in Transport Times an accessible piece summarising some of the discussion.

j2t#067

If you are enjoying Just Two Things, please do send it on to a friend or colleague.