30 November 2022. Solarpunk | Islamophobia

Solarpunk, solarities, and visions of beyond the human. // ‘Love us when we’re lazy, love us when we’re poor’

Welcome to Just Two Things, which I try to publish three days a week. Some links may also appear on my blog from time to time. Links to the main articles are in cross-heads as well as the story. A reminder that if you don’t see Just Two Things in your inbox, it might have been routed to your spam filter. Comments are open.

1: Solarpunk, solarities, and visions of beyond the human

I like the Public Books site, which allows academics to write at length on serious books. Stacey Balkan’s recent review of a suite of books on the politics of solar power doesn’t disappoint. By politics I don’t mean trivialities such as where you might be permitted to instal solar panels. The subject here is perhaps better described as the political economy of solar power. Or, better still, its social economy.

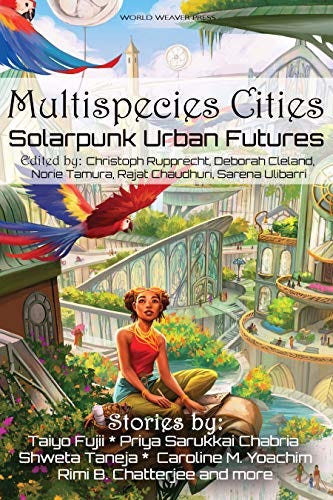

The books reviewed here are Solarities: Seeking Energy Justice, by the After Oil Collective; Solar Politics, by Oxana Timofeeva; and Multispecies Cities: Solarpunk Urban Futures, edited by Christopher Rupprecht and others.

I probably ought to start with ‘solarpunk’:

The word “solarpunk” encompasses both a political ideal and a burgeoning subgenre of climate fiction, which celebrates the brilliant abundance of the sun as well as what has been termed “solarity.”... Solarpunk stories are drenched in the spectacular light of this solarity. Perhaps more critically, they advance a liberatory politics that marshals solar power in the spirit of a true energy commons. Characters in solarpunk fictions inhabit convivial spaces where historically marginalized communities and a nonhuman landscape that includes “comrade sun” live in economic harmony.

(The Sun, via Wikimedia. Public domain.)

This abundance opens up the prospect of a new type of energy politics, and energy economics. Precisely because sun is everywhere on the planet, and because the means of harvesting it tend to be relatively simple to produce, it opens the possibility that energy production could belong to the communities that use it, rather than being part of a global system of capital and investment. Coming into it via solarpunk opens up an interesting conversation on the way in which genre can foreshadow possibility. The cultural roots of futures thinking, to take a sledgehammer to this one:

Arguably, the solarpunk genre stands as an imaginative bulwark against the forces of solar capitalism—perhaps, too, against forms of solar fascism that may seem imminent given our current political trajectory... In several ways, the genre resembles forebears like steampunk and dieselpunk, both of which occasioned similarly revolutionary moments in energy and energy use—ruptures in what sociologist Patricia Yaeger famously termed the global “energy unconscious.”

I wasn’t familiar with Yaeger’s theory before—not quite famous enough to reach this London backwater—but it is genuinely interesting. Yaeger suggests that we should look back at literary periods through the lens of the energy that powered them: the age of coal, rather than Victorian literature; the age of petroleum instead of modernism.

Balkan suggests that the late Victorian steampunk novels (H.G. Wells’ The Time Machine, for instance) are about the dark extraction of coal and the beginnings of the transition to oil, perhaps in the same way that solarpunk is about the transition away from it.

(Steampunk hat, by culturalibre. Via Open Clip Art.)

It’s a long article that makes a complex argument, and it is going to lose something in my account here. But the thread that runs through these books, at least on my reading of Stacey Balkan’s review, is that the culture and politics of solarpunk is capable of making utopian demands, even if it takes more than this to fulfil them.

Reading Solarities, for example, she observes that solarpunk

also seeks something more intangible: a planetary commitment to collectivism and collectivist justice for historically dispossessed communities and the global landless—as well as for the vast communities of nonhuman actors... whose labor has long been understood as a gift that requires no return on investment. Such a commitment, according to After Oil, must indeed demand that “energy is not (understood as) merely fuel for endless human consumption and (endless) growth but as a gift that makes life possible.”

This theme of the non-human also runs through Timofeeva’s book Solar Politics. The idea of ‘solarity’, mentioned above, refers to

“a state, condition or quality developed in relation to the sun, or to energy derived from the sun.”

Put like that, it’s both descriptive more than prescriptive. Timofeeva suggests that it needs to be understood in a political content:

one in which the sun is a “comrade”—an ally in a multispecies assemblage constitutive of a “cosmic solidarity.” Such a cosmic imaginary will break “the promethean vicious circle of worship and extractivism” that has long characterized the energy politics of Timofeeva’s Siberian home... (This) chimes, too, with one of the central mandates of solarpunk: the creation of a multispecies, collectivist commons. This would be a planetary commons—a “cosmic solidarity” par excellence—as well as a decentralized one.

If this does indeed sound utopian, the politics for it are already coming into existence in places such as Puerto Rico, where localised solar energy is helping to rebuild after disastrous hurricanes.

The third book in this set is a collection of stories, Multispecies Cities: Solarpunk Urban Futures. Some of the stories bring to life this idea of a multi-species future. According to the introduction,

the storytellers of this volume serve not only their well-established roles as aesthetes of a stricken time but also of designers and navigators of a tomorrow to look forward to.”

Stories are always hard to summarise in a format like Just Two Things—they need more space to breathe—but there’s a flavour of the collection in the description of Phoebe Wagner’s story “Children of Asphalt.”

The story is set in a future where the asphalt—that “tarred rock that littered the city”—had been removed in the interest of cultivating land for a vibrant assemblage of human and nonhuman “kin.”... Wagner describes an unfamiliar, amphibious creature who washes in from the Pacific Ocean to create nests for incoming pregnant mothers. Not unlike García Marquéz’s tragic Esteban, who ultimately colonizes the small village that has taken him in, the “landrus” transforms all the arable coastal land into a network of nests.

But this alien is not a destroyer, and the response of the humans is not to try to kill them. Instead, “in a post-colonial twist”, they become curious about what the “landrus” can offer them.

Balkan reminds us that it’s easy to imagine that the obstacles to a different kind of energy future are technical ones. Instead they are ideological ones (it’s easier to imagine the end of the world, etc). The benefit of solarpunk is that offers a new frame for our imaginations.

I find far greater value in the transformative power of the imagination, and I am drawn, as a result, to the generative, instrumental, worldbuilding potential of solarpunk—its ability to imagine new, workable infrastructures and assemblages... Solarpunk worlds, meanwhile, are rooted in infrastructural logics that promise a viable (and truly revolutionary) way forward.

2: ‘Love us when we’re lazy, love us when we’re poor’

I listened to a talk last week by the academic and writer Suhaiymah Manzoor-Khan last week, on ‘the language of violence’. She combines her academic work with being a poet and a playwright, currently writer-in-residence at Leeds Playhouse.

I’ll come back another time to her theme on the language of violence—this is about the language of ‘terror’ versus the language of ‘security’, which is also the subject of her book Tangled in Terror.

But she took the unusual step of opening her talk with a poem, which I discovered later was also online. It was written in the wake of the knife attack in London Bridge in 2019. I like the turn that comes around two-thirds of the way through.

There’s also a print version if you prefer to read your poetry.

j2t#400

If you are enjoying Just Two Things, please do send it on to a friend or colleague.