3 November 2021. South Africa | Jellyfish

Taking stock of South Africa through a 2,000km road trip; Jelly fish and nuclear power stations don’t mix.

Welcome to Just Two Things, which I try to publish daily, five days a week. (For the next few weeks this might be four days a week while I do a course: we’ll see how it goes). Some links may also appear on my blog from time to time. Links to the main articles are in cross-heads as well as the story.

#1: Taking stock of South Africa: a 2,000 kilometre road trip

There are elections in South Africa this week, and there was an extraordinary piece of writing in the country’s Daily Maverick paper a few weeks ago by Marianne Thamm, an impression-laden series of notes from a symbolically-designed 2,000 kilometre road trip she took across the country.

Some of it requires a bit of knowledge of South African history—political and racial—but in general the writing carries you through.

Here are some snapshots.

Part of South Africa’s crisis has been its failure to deliver basic utilities in a reliable way—electricity and water, but also transport—largely because of corruption and mismanagement. Water runs through her story.

In Richmond, in the Northern Cape, for example:

In the 1800s Richmond’s mineral-rich water springs and pristine air attracted European aristocrats seeking cures for lung complaints. The springs still exist but the water that once ran freely through the sluices in the town is damming up somewhere in the broken system.

Right now, the furrows, once used by residents to water vegetable gardens, are filled with litter and sand.

Len Rundle would like to see the water running again through the town.

“When the municipality took it over it lasted three months, then it stopped running. Pumps were simply not repaired. We can take it back. The sluices. This is what makes these towns authentic. These things must work,” he says emphatically.

Orania, in contrast, is a kind of Afrikaaner enclave, where Thamm—an white Afrikaans-speaking woman is able to pass without comment, despite her very differennt political views—which issues its own form of currency.

Pecan nut orchards, berries, straw bale houses, tourists (from SA and elsewhere, all mostly white), a neat resort next to the Orange River, fields of gold and green, an industrial area, a pipeline pushing water uphill.

Not a single black face, not one. In two days.

To understand Orania you have to follow the money. Both the rands and the ora – the cult’s own currency.

Did I say cult?

Essentially this is the ideology that underpins the entire Afrikaner Volkstaat edifice. They will tell you it is about culture, language and history, but it isn’t.

If you are a wealthy Afrikaner, Orania will bless you. You bring gifts, it gives back. Like Jacob Zuma’s ANC.

(Orania’s scrip currency. Photo by Marianne Thamm, via Daily Maverick)

In truth, when I was reading her article I got a bit obsessed with Orania, which I had not heard of before. White Afrikaaners who arrive destitute are welcomed and put to work—and paid in the scrip currency of Ora, not rand. It runs its own Volkschool. Thamm asks, inevitably, if black people can visit and sleep over:

“They can, but they don’t really feel comfortable,” said our guide.

As she says, self-determination is often admirable. But what is guiding it also matters:

One can admire the determination to be self-sufficient, the innovations in energy and farming. But Orania is ultimately a nationalist, capitalist kibbutz guided by the ideas of a cult of austere “freedom-loving” ancestors – Kruger, Steyn, Hertzog, Malan, Strijdom, Verwoerd, Vorster.

Orania hosts a museum to the former Prime Minister Verwoerd, in his former house here. He is generally regarded as the architect of apartheid, yet, in 1995 Mandela visited his widow Betsie here in one of his many acts of forgiveness. Yet there’s nothing in the museum recording this historic event; it’s almost as if the residents want to airbrush away this bit of history.

Brandfort, Winburg... she has picked out her itinerary symbolically. Brandfort was the home of Winnie Mandela, Winburg the sight of the not-at-all-totalitarian Voortrekker memorial, unveiled in 1968, just at that point when the winds of international protest started to blow against the apartheid regime.

The towns are all suffering from lack of investment, and as importantly, from endless political infighting.

Too good to be true, at least from a narrative perspective, but at the monument she meets a destitute Afrikaaner who asks her if she ons a farm.

As she heads across the country, the roads gets worse, of course.

In a dark and brewing electrical thunderstorm we hit a Free State crater, buckling the rim and shredding the tyre, beyond repair.

The spare will not yield from its casing under the vehicle. An unforgiving bolt on tight. Help arrives from Ficksburg about 30 minutes away, where the tyre business is booming, of course.

Branches all over the main road. R1,700, just like that. That week it is announced that Sam Mashinini, the MEC for Police, Roads and Transport, has been fired. I feel like sending him the bill.

The roads are like this because rail has collapsed. Rail has collapsed because everyone stole from Prasa until there was nothing left to steal.

The Daily Maverick, and indeed Thamm herself, have been assiduous in its pursuit of the story of the state capture of South Africa and the corruption that went with it. Some of the examples have been eye-opening.

We don’t yet know what the outcome of the elections will be. But sooner or later the combination of open elections and state corruption and mismanagement of services doesn’t end well for the government. Even for a government that started out 30 years ago with Mandela’s towering moral authority.

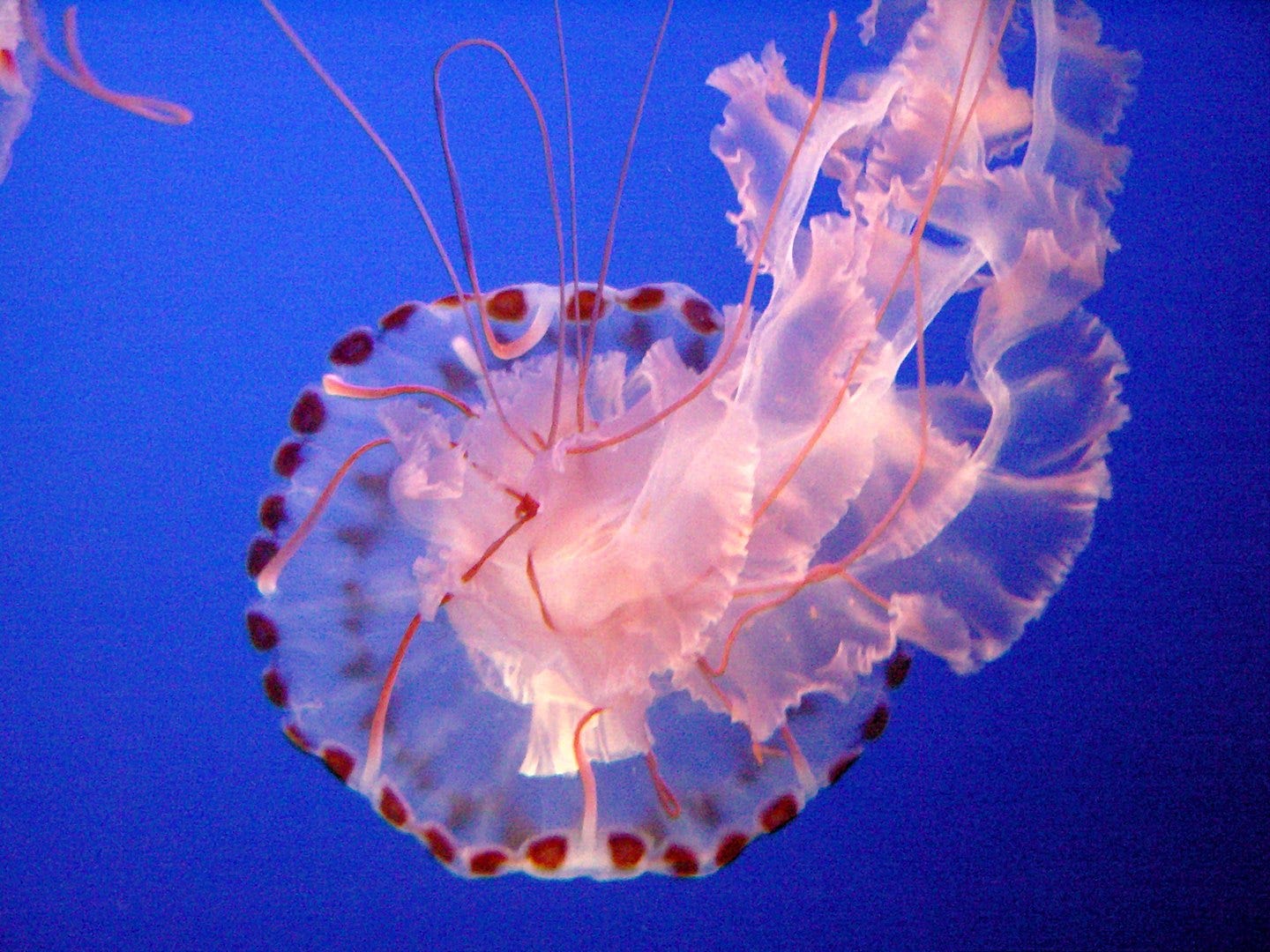

#2: Jellyfish and nuclear power stations don’t mix

Jellyfish have a particular place in the futures pantheon because they are one of the creatures in the futures ‘menagerie’ created by the post-normal times group.

So ‘black swans’ these days probably (the definition has proved malleable) represent low-probability high-impact wildcards, if probability means much in a world of complex tightly-connected systems, and ‘black elephants’ represent predictable surprises, or, in Drucker’s phrase, ‘the future that has already happened’, and is working its way through the system towards us.

Black jellyfish, in contrast, are events that are difficult to anticipate because they are ‘unknown knowns—things we think we know and understand but which turn out to be more complex and uncertain than we expect’.

From memory, the source of the jellyfish as the icon of this kind of change was an incident in Brisbane when the USS Reagan—the nuclear-powered largest naval vessel in the world—was visiting Australia in a period of unseasonably warm weather. The jellyfish started to bloom, and ovewhelmed the carrier’s condensers, forcing those on board to evacuate. The black jellyfish, in other words, represents an unanticipated outcome brought on by change in the configuration of a complex system.

(Photo: Fred Hsu, under a GNU Free Documentation Licence, via Wikipedia)

This is by way of a long preamble to a recent story in Atomic Bulletin about more examples of jellyfish causing damage to nuclear power stations.

Scotland’s only working nuclear power plant at Torness shut down in an emergency procedure when jellyfish clogged the sea water-cooling intake pipes at the plant, according to the Scotland Herald this week. Without access to cool water, a nuclear power plant risks overheating. The intake pipes can also be damaged, which disrupts power generation. And ocean life that gets sucked into a power plant’s intake pipes risks death.

It’s a phenomenon that’s been noticed for a few years now, but it has expensive consequences when a power station has to shut down, and it’s hard to manage. There’s research into whether better monitoring might be a solution, using drones, which starts sounding like a winning line on a futures fruit machine (‘nuclear power!—jellyfish!—drones!). Acoustics might also work.

The immediate problem is—as the captain of the USS Reagan knew—is that in the right conditions jellyfish blooms appears and then grow rapidly. The systemic problem is that in general climate change is good for jellyfish (because they respond well to warming waters) and in particular nuclear power stations are also good for them (because they warm the waters offshore from them). And oceanic pollution has lowered oxygen levels in the ocean, which jellyfish tolerate better than other sea creatures. It’s almost as if the Anthropocene was designed to help jellyfish to prosper.

So mitigation and monitoring seems to be the best option. Because the jellyfish isn’t going away:

(T)hey are nothing if not resilient. Jellyfish are 95 percent water, drift in topical waters and the Arctic Ocean, and thrive in the ocean’s bottom as well as on its surface. Nuclear power plant operators might take note: Older-than-dinosaur jellyfish are likely here to stay.

j2t#199

If you are enjoying Just Two Things, please do send it on to a friend or colleague.