3 May 2022. Buildings | Cars

‘Long life, loose fit, low energy’. // The problem with autonomous cars are their drivers.

Welcome to Just Two Things, which I try to publish daily, five days a week. Some links may also appear on my blog from time to time. Links to the main articles are in cross-heads as well as the story. Recent editions are archived and searchable on Wordpress.

1: ‘Long life, loose fit, low energy’

One of the pleasures of writing regularly is that every so often readers tell you about something you didn’t know about. I wrote something about cities a few weeks ago, and David Aplin mentioned Alex Gordon to me—President of the Royal Institute of British Architects in the 1970s—who said in 1972 that the mantra for good building should be ‘long life, loose fit, low energy.’

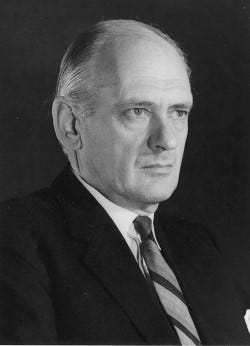

(Alex Gordon. Photo: RIBA)

A little bit of light research found a piece from 2011 by John Bale reflecting on Gordon’s view:

The low energy bit is now generally accepted, but the first two requirements (that buildings need to have a degree of permanence, and be capable of adaptation to a variety of uses over their lives) seem to be somewhat ignored. The intended life-span of a building is frequently unstated by designers, design is often tailored closely to current needs as if they are unlikely to change, and many buildings are structurally unsuited to adaptation. And yet it seems that most of my favourite buildings have lived long and chequered lives, served a variety of occupants, and been frequently adapted and refurbished.

Bale was writing about the same time that it had been announced that a chunk of the Broadgate building, near Liverpool Street in London, was about to be demolished after around 20 years. There were some aesthetic arguments about that at the time, but of course the real problem is one of resources:

(C)an it really make environmental sense to demolish apparently sound buildings a mere 20 or so years into what might have been an expected life of 60 or 80 years? There is a need for someone to assess the carbon implications of such decisions, taking account of the original environmental investment, the implications of demolition and replacement, and the opportunities for environmental improvement of the existing building.

Of course, Gordon’s phrase also sounds a bit like Stewart Brand’s argument in How Buildings Learn— that buildings should be designed and built so they can be refurbished and reused. The famous diagram from that book looks like this:

(Stewart Brand, How Buildings Learn.)

There’s a helpful explanation of this in a recent article by Robert Bogue:

The changes in the stuff is very rapid compared to the rest of the building. Let’s look at each layer:

Site – Permanent.

Structure – The most persistent part of the building. The lifespan of structure can be measured in decades to centuries. When the structure changes, the building has changed.

Skin – The façade or outer face of the building is expected to go out of style and to be replaced every 20 years or so to keep up with fashion or technology.

Services – These are things like HVAC, elevators, etc., which simply wear out over the period of seven to fifteen years.

Space Plan – Commercial buildings may change occupancy every three years or so, driving a change in the way internal space is allocated. Domestic homes in the US are, on average, owned for 8 years.

Stuff – These furnishings and flairs change with the seasons and the current trends.

The rates of change for different layers occurring at different times creates sheering forces, where the slower-moving layers constrain the faster-moving layers.

That might sound familiar, because it’s a bit like Brand’s ‘pace layers’ model in The Clock of the Long Now, and Brand has explained elsewhere that he wouldn’t have got the pace layers model if he hadn’t written How Buildings Learn first.

There are reasons why buildings—particularly commercial buildings—get knocked down after 20 or 25 years rather than 60 or 100. Broadly, the skin and the especially the services date too quickly, and are not designed in a way that makes them straightforward to upgrade or replace.

Bogue also suggests that there’s something in the architecture profession that contributes to this:

What gets you into Architectural Digest isn’t how tenants love a building. What gets you into Architectural Digest are the pictures taken before people are in the building. It’s all about the design and none about the use. While some progress is being made in getting better metrics that measure – gasp – what occupants think, the progress is painfully slow... Architects aren’t motivated to make the actual users happy with the building they get.

As it happens, there’s a paper online that assesses a number of Australian award-winning buildings against Gordon’s ‘3L’ criteria of ‘long life, loose fit, and low energy.’ In his 2014 article, Craig Langston says this can be summarised as ‘durable, adaptable and sustainable’. All three are measurable. His purpose in the paper is to assess whether our views these days of what good architecture is aligns with Gordon’s mantra.

To my surprise, and maybe to his, he finds that there’s a decent alignment:

(B)uildings that have recently been recognised for architectural excellence in Southeast Queensland portray the principles of long life, loose fit and low energy, and hence meet Gordon’s ‘test’ for good architecture... durability suggests both lower maintenance and replacement costs due to reduced decay, summary adaptability suggests both lower rates of churn and refurbishment costs arising fromfunctional obsolescence, and sustainability suggests lower energy, water and other inputs through a more responsive environmental design.

This news, however, doesn’t seem to have reached the ears of commercial developers yet. Construction represents something like 10% of emissions (the exact figure isn’t known, and there is no legal requirement to measure them.)

But what’s striking is that almost all the proposals to reduce them—summarised in a recent Parliamentary Office for Science and Technology briefing paper—sound awfully like Alexander Gordon’s ‘long life, loose fit, and low energy.’

2: The problem with autonomous cars are their drivers

There’s an interesting post at the OUP blog about autonomous vehicles and the effects of such technologies on people’s cognitive performance.

There has been ample review of the underlying technology, but there are far too few discussions about the role of people. What happens when we replace human judgment with technology, a situation that psychologists call “cognitive offloading”? … Cognitive offloading transfers routine tasks to algorithms and robots and frees up your busy mind to deal with more important activities.

However, this has unintended consequences, and even if the use of autonomous vehicles at scale seems like a receding horizon right now, we’ve learned quite a lot about these consequences from aviation and automation. In summary, we also offload learning and judgment. The problems come in two varieties:

First, cognitive offloading can lead to forgetfulness or failure to learn even basic operating procedures. The problem becomes acute when equipment fails, when the weather is harsh, and when unexpected situations arise. In aviation, even carefully selected and highly trained pilots can experience these deficits.

The second is that people over-estimate the value of offloading, and this leads to over-confidence:

People may fail to grasp how offloading may degrade their abilities or how it may encourage them to apply new technologies in unintended ways. The result can be consequential. The Boeing 737 Max incidents were attributed, in part, to overconfidence in the technology. One pilot even celebrated that the new technology was so advanced, he could learn to master the newly equipped aircraft by training on a tablet computer.

In the aviation sector, new technologies are implemented alongside “training and constant updating” that helps pilots understand the limits of the technology.

Christopher Kayes, who wrote the piece, suggests that we can translate this learning across the the autonomous vehicle sector.

I’m not so sure of this. One sector is highly regulated, and can impose conditions on its users. The other comes with a long history of individualist behaviour and user over-confidence. Kayes gives an example of how attempts at self-regulation plays out with Tesla drivers:

Tesla’s Safety Score Beta, for example, monitors the driving habits of Tesla owners and only activates the self-driving feature for drivers who meet their criteria on five factors: number of forward collision warnings, hard breaking, aggressive turning, unsafe following, and forced autopilot engagement. But… there is growing discontent among drivers who fail to make the safety cut after shelling out nearly $10,000 for the self-driving feature.

—

(Tesla Safety Score Beta. Image via The Last Driver License Holder)

Update

I wrote here recently about the fight by Amazon workers to unionise. 233 US branches of Starbucks have also filed for unionisation votes with the National Labor Review Board. 31 have already unionised, often by large margins. There’s a piece on Naked Capitalism about this:

It seems as though the standard anti-union corporate playbook may have reached its limit as workers across the United States are seeing the benefits of labor organizing in the face of undignified work, meager pay, unpredictable hours, little to no benefits and few rights. One of the most effective corporate anti-union tactics has been to disparage unions for charging fees (monthly or annual dues) to finance their protection of workers. ... But this tactic failed in the face of SWU’s organizing. “Before a union goes public, we’re inoculating our organizers,” said (organiser Joe) Thompson. “We’re telling them, ‘here’s exactly what Starbucks is going to say; here’s why it’s wrong.’”

j2t#308

If you are enjoying Just Two Things, please do send it on to a friend or colleague.